TONY BURKE speaks to Gambian kora player SUNTOU SUSSO

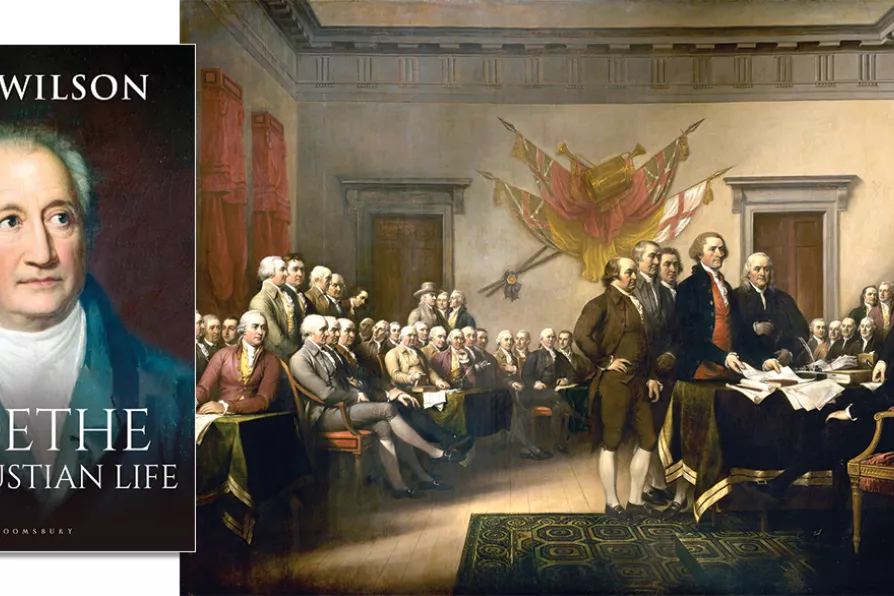

HERALDING THE UNKNOWN: Declaration of Independence by John Trumbull features the Commission of Five submitting the text of the Declaration of Independence. From left to right, John Adams, Roger Sherman, Robert Livingston, Thomas Jefferson and Benjamin Franklin, who actually were never in the same room at the same time

[US Capitol/Public domain]

HERALDING THE UNKNOWN: Declaration of Independence by John Trumbull features the Commission of Five submitting the text of the Declaration of Independence. From left to right, John Adams, Roger Sherman, Robert Livingston, Thomas Jefferson and Benjamin Franklin, who actually were never in the same room at the same time

[US Capitol/Public domain]

Goethe: His Faustian Life

AN Wilson, Bloomsbury, £25

AFTER their detailed and in-depth research, biographers may well end up either loving or loathing their subject. There can be no doubt that AN Wilson has great affection for a man he believes a genius and one of the most remarkable figures in modern history, although the character the reader will meet is not one who emerges as altogether admirable.

Like most biographers, Wilson discovers the figure he is looking for. His study presents an “exquisite lyricist, passionate scientist, soulful lover, conservative statesman, [who was] also a wild man, obscene and out of control, foul mouthed, coarse and alcohol fuelled.”

It would not be unfair to suggest that “the prodigious size of the literary output” of this poet and novelist, playwright, scientist, philosopher and even psychologist, who has the kind of standing in Germany that Pushkin has in Russia or Shakespeare in England, is virtually unknown to British readers.

ANDY HEDGECOCK relishes an exuberant blend of emotion and analysis that captures the politics and contrarian nature of the French composer

Science has always been mixed up with money and power, but as a decorative facade for megayachts, it risks leaving reality behind altogether, write ROX MIDDLETON, LIAM SHAW and MIRIAM GAUNTLETT