New releases from The Thumping Tommys, Dan O’Farrell and The Difference Engine, and Sean Taylor

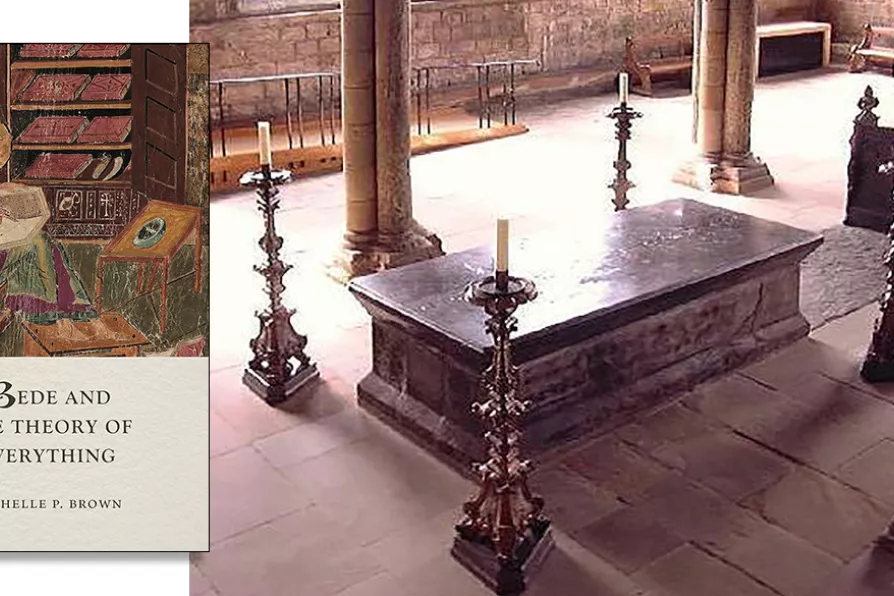

Bede’s tomb in Durham cathedral

[Prazak/CC]

Bede’s tomb in Durham cathedral

[Prazak/CC]

Bede and the Theory of Everything

Michelle P Brown, Reaktion, £16.95

Whilst not exactly a household name, born 1,300 years ago (673 AD) in the north of England, the Venerable Bede is probably the greatest scholar of the Anglo Saxon period, most famous for his book, the Ecclesiastical History of the English People, and hence regarded as the father of English history.

Ecclesiastical History starts with the Roman invasion of Britain, covers 800 years of British history, explores political and social life together with the rise of the early Christian church. It remains an important source both of facts, and for what early Anglo Saxon life was like.

But Bede also wrote on a large number of other subjects, science, music, poetry, biblical commentary. One of his early works, On the Nature of Things, is a collection of contemporary theories that includes cosmology, time and arithmetic, and later, Bede calculated the first tide tables and calendar dates.

GORDON PARSONS is enthralled by an erudite and entertaining account of where the language we speak came from

LOUISE BOURDUA introduces the emotional and narrative religious art of 14th-century Siena that broke with Byzantine formalism and laid the foundations for the Renaissance