Labour prospects in May elections may be irrevocably damaged by Birmingham Council’s costly refusal to settle the year-long dispute, warns STEVE WRIGHT

THE first week of February saw a couple of labour movement occasions centred on Shropshire and north Wales.

It was the 200th anniversary of the event known as “Cinderloo,” where miners protesting about wage cuts were attacked by the Shropshire yeomanry. Several were killed and others put on trial at Shrewsbury.

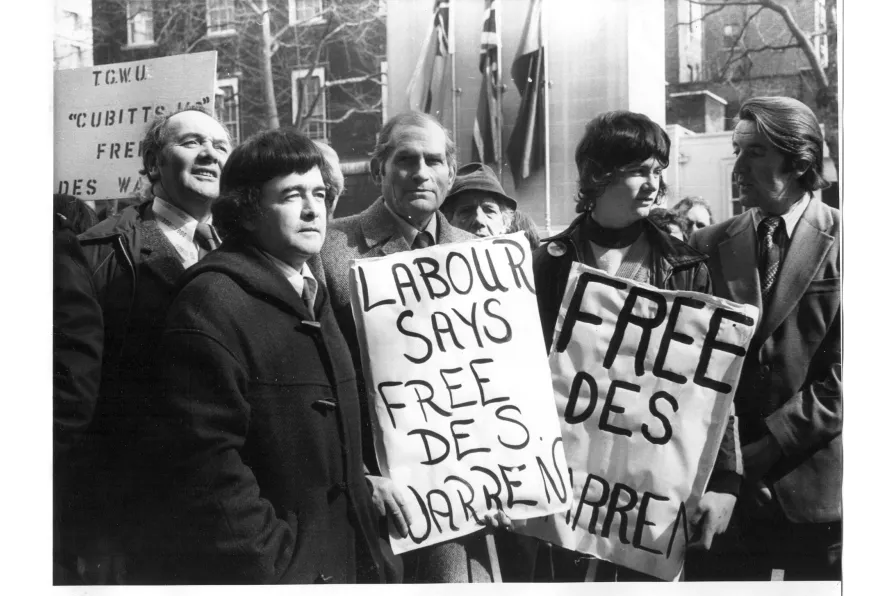

Over two days in the same week was the long overdue appeal by building workers convicted as part of the 1972 national building workers’ strike, in which the matters at issue also took place in the Shrewsbury area.

Inspired by a hit TV show, KEITH FLETT takes a look at the murky history of undercover class war

The government cracking down on something it can’t comprehend and doesn’t want to engage with is a repeating pattern of history, says KEITH FLETT

KEITH FLETT traces how the ‘world’s most successful political party’ has imploded since Thatcher’s fall, from nine leaders in 30 years to losing all 16 English councils, with Reform UK symbolically capturing Peel’s birthplace, Tamworth — but the beast is not dead yet