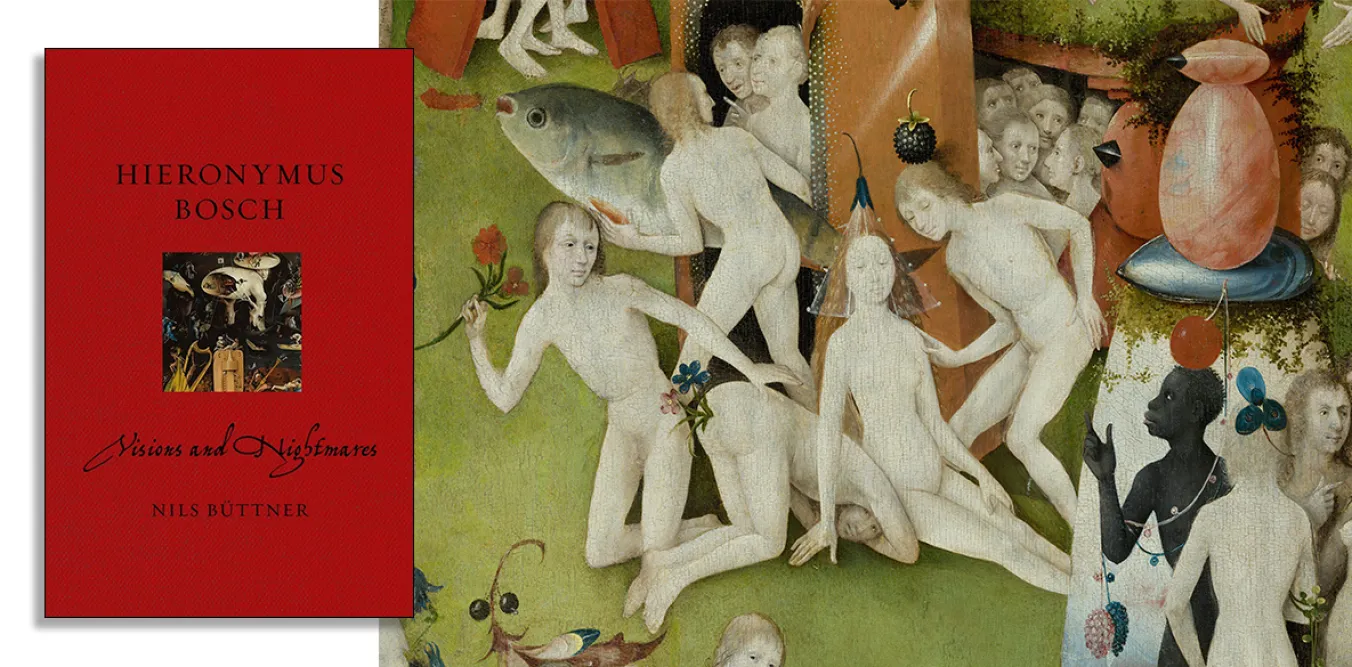

Hieronymus Bosch – Visions and Nightmares

Nils Buttner, Reaktion Books, £14.95

ACCORDING to psychologists at the University of Vienna, our appreciation of visual art is enhanced if work is open to multiple interpretations. When it comes to the painted image, we love an enigma.

In this accessible introduction to the work of Hieronymus Bosch, Nils Buttner acknowledges that inscrutability is a factor in the Dutch painter’s enduring appeal. Buttner’s relish for the mysterious and multi-layered aspects of Bosch are, however, tempered with analytical enquiry.

From the outset, he notes the impact of scientific enquiry on perceptions of the artist. In 1937, forty-one paintings were attributed to Bosch; by 2013, dendrochronology and stylistic analysis had reduced the list to twenty. Within this redefined oeuvre, traditional Christian iconography is represented far more frequently than the "darkly fantastic" scenes for which he is best known.