GORDON PARSONS applauds a marvellous story of human ingenuity and youthful determination, well served by a large and talented company

MATTHEW HAWKINS relishes the valiant defiance of two gay Scottish painters whose example resists both collectors’ taste and historical fiction

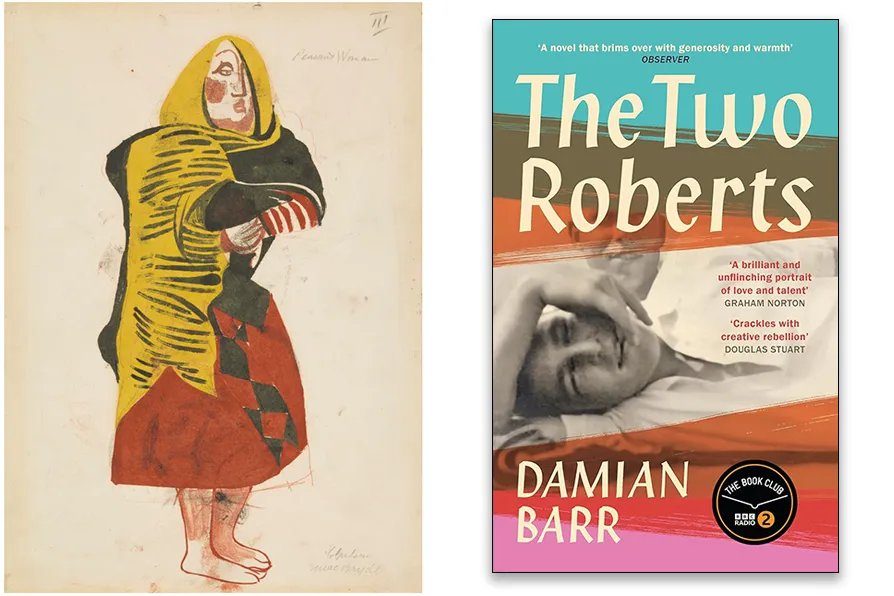

Robert Colquhoun, Robert MacBryde; Peasant Woman (Costume Design for 'Donald of the Burthens') [Pic: The estate of Robert Colquhoun/All Rights Reserved 2017/Bridgeman Images and the estate of Robert MacBryde]

Robert Colquhoun, Robert MacBryde; Peasant Woman (Costume Design for 'Donald of the Burthens') [Pic: The estate of Robert Colquhoun/All Rights Reserved 2017/Bridgeman Images and the estate of Robert MacBryde]

The Two Roberts

Damian Barr, Canongate, £18.99

INDUSTRY and construction figure significantly in the tale of this creative couple.

In Ayrshire, a century ago, tanner’s boy Bobby MacBryde spent his teens nailing soles to uppers. He saved his wages against his projected future at Glasgow School of Art where he would study alongside Robert Colquhoun – himself a near-miss industrial designer. They cleaved together: an item, an affair, a productive force. This much comprises a true story.

An acreage of privately commissioned artwork would flow from their adjacent easels, all striking stuff and technically flawless. At the point of discovery, their work was influential - lauded by contemporaries like Francis Bacon and Lucien Freud.

The post-war art market did not favour their work. It is said they did not “play the game.” But was it ever a game? Their lives were hand-hewn original. Reality, outside their tight circle, was violently toxic. Vital material output placed food on the table; yesterday’s still-life becoming today’s edible ration.

In today’s publishing game however, extant scholarly works on these two artists aren’t thought to square with the readership identified for this tangible romantic yarn. Or is it a screenplay? Damian Barr conjures place (Glasgow/Soho/Paris/Sussex) with precision and relish. His reported conversations banter and bicker accessibly. The march of history/atrocity lurches past.

The Two Roberts is a portrait of souls in a consensual bind of refuge. Key figures offer temporary havens. The boys grift and graft across decades. They hit a seam of depravity. They hit the bottle.

They knew of no model for their open-secret shared life. They “exhibited together” creatively and destructively, in settings legit or lewd. Barr brings The Two Roberts to vibrant life, depicting them as committedly beloved of each other, encouraging the reader to bask in their primal warmth.

The materiality of their paintings is not reliably conjured. Focus rests instead on historical context and other ephemera. The approach allows for great cameos. It fits an agenda. Imaginative supposition and selective fact permit depiction of these painters as unsung and needful of contemporary benison. This can feel gratuitous.

But these Roberts developed viable modus operandi. Meanwhile, they expected to be perceived as marginal trash and they positively colluded in this judgement – as makes for a great immediate read.

Satirical episodes add pace. Colquhoun and MacBryde’s 1951 collaboration with Diaghilev-era choreographer Massine features as caricature. Were there no inspiring creative discussions? I struggle to believe the Roberts would be incurious about Massine’s early ballets made with Picasso, Matisse, Miro and so on – masters, with whom our Scots shared this episode of equivalence, amid the efficient ambitions of emerging British ballet. Or perhaps it really was all about sending designs by post then turning up sozzled on opening night and foraging the interval ashtrays?

Painters amount to more or less than their product. These Roberts enjoy permanent status in terms of the presence of their work in good public and private collections. They now reside in the embrace of this poetic historical fiction, where they still retain their valiant defiance.