ALAN McGUIRE welcomes the complete poems of Seamus Heaney for the unmistakeable memory of colonialism that they carry

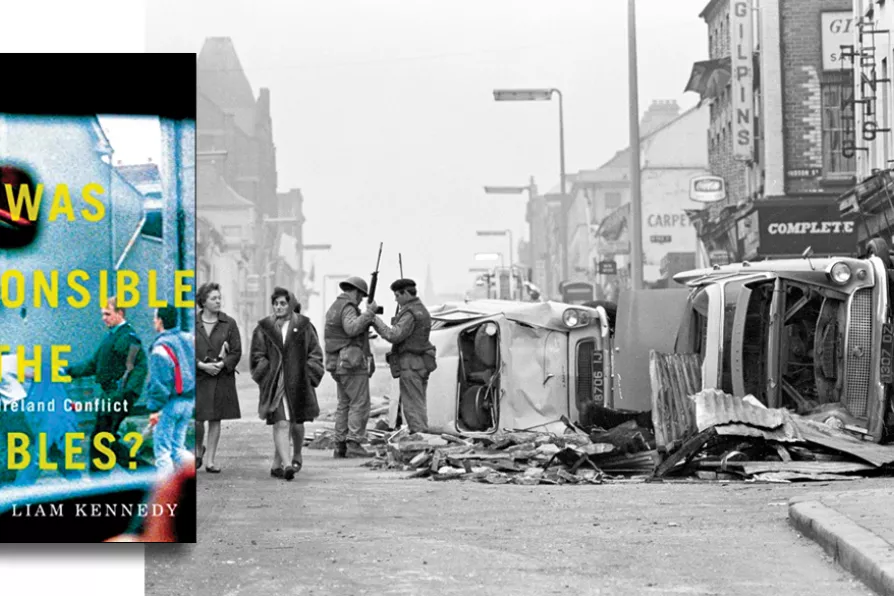

UNDER OCCUPATION: Shankhill Road, Belfast, 1969

UNDER OCCUPATION: Shankhill Road, Belfast, 1969

THIS book by Liam Kennedy does not claim to be an objective assessment of the Northern Ireland Troubles and the author does not attempt to conceal his political views.

His comment that Dan Breen, an Irish War of Independence guerilla, was a “leading gunman from my own county” gives a clue to his perspective, not just on the Provisional IRA but the early 20th-century struggle against the British.

Kennedy emphasises statistics of violent deaths and injuries to justify the conclusion that the Provos were mainly responsible for the Troubles. Those statistics, and the Provos’ prosecution of a long war, underpin the book’s main thesis.

A new group within the NEU is preparing the labour movement for a conversation on Irish unity by arguing that true liberation must be rooted in working-class solidarity and anti-sectarianism, writes ROBERT POOLE