MARJ MAYO recommends a lyrical and disturbing account of the tragic suicide in Venice of Pateh Sabally, a refugee from the Gambia

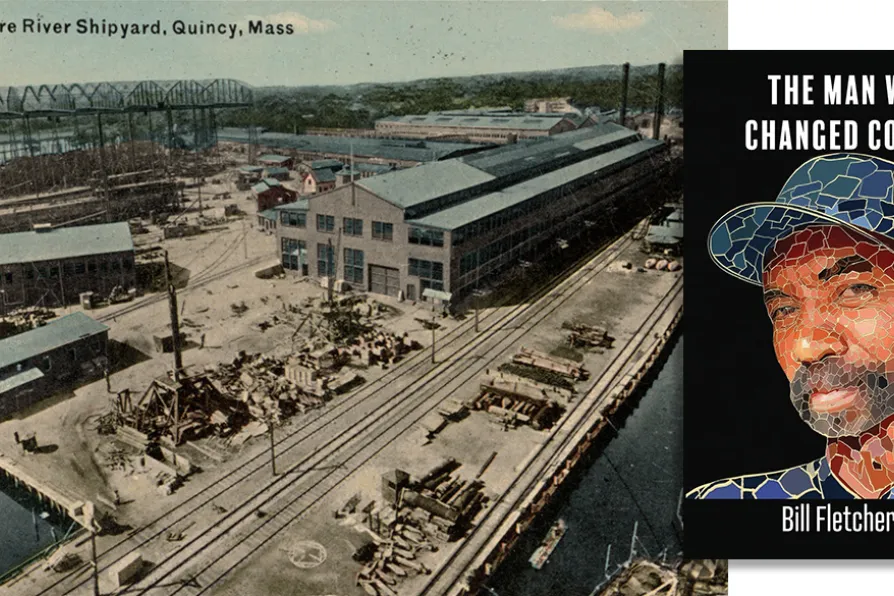

View at the Fore River Shipyard, Quincy, Mass.

[digital commonwealth.org/CC]

View at the Fore River Shipyard, Quincy, Mass.

[digital commonwealth.org/CC]

The Man Who Changed Colors

Bill Fletcher Jr, Hard Ball Press, £13.45

DASHIEL HAMMETT, the key writer in the 20th-century detective novel both in print and in screen adaptations of his work, had it right. “The Butler Did It,” the answer to the mystery in a 19th-century British novel, had the logic of the real-life crime upside down. It was the banker or the real estate developer or the police chief who did it and mostly got away with it.

Hammett, a militant anti-fascist and sometime lecturer at New York’s lefty Jefferson School, was blacklisted in Hollywood, although his novels could not be banned any more than audiences could be kept from watching “The Maltese Falcon.” Such is the fate of the Detective Left.

PAUL BUHLE recommends an eminently useful book that examines the political opportunities for popular anti-fascist intervention

JOHN GREEN welcomes a remarkable study of Mozambique’s most renowned contemporary artist

PAUL BUHLE agrees that a grassroots movements for change in needed in the US, independent of electoral politics