Climate activist and writer JANE ROGERS introduces her new collection, Fire-ready, and examines the connection between life and fiction

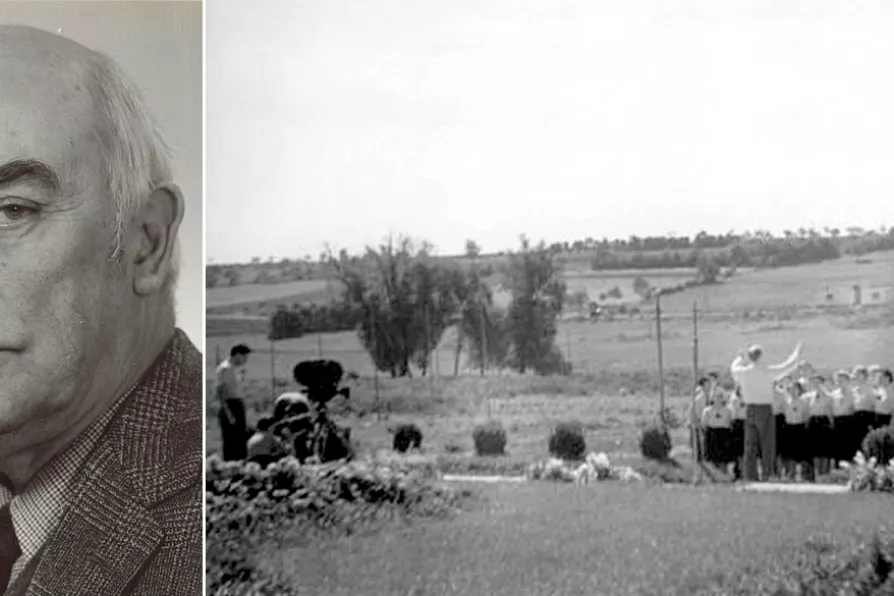

(L) Alan Bush; (R) Alan Bush conducting the Workers' Music Association Choir singing Lidice on the site of the razed Czech village in 1947

[Courtesy of the Alan Bush Trust]

(L) Alan Bush; (R) Alan Bush conducting the Workers' Music Association Choir singing Lidice on the site of the razed Czech village in 1947

[Courtesy of the Alan Bush Trust]

IT is that time of year again, and for many groups across Britain (and the world) musical summer schools are running, sharing wonderful music together and making a hell of a noise. The Workers’ Music Association (WMA) is no exception and now we finally get to enjoy the 75th edition of the summer school, one strange upside of the pandemic being that we get to celebrate the summer school twice!

The summer school was founded to bolster the various activities the WMA was doing shortly following World War II. These other activities included journal publications, an LP subscription scheme, score publications (including songs for Morning Star stalls), and supporting the various socialist choirs. However, over time, due to costs, people power, and a variety of other factors the summer school went from strength to strength and outlasted some of the other elements of work.

When you are reading this, we’ll be getting stuck into the variety of activities, making new friends, and simply having a go at lots of other musical things. The courses are varied, and currently run by a collection of talented volunteers, many of whom making up the backbone of the WMA today. As a big anniversary, the 75th is a chance to reflect on the past of the summer school.

ANN HENDERSON on the exciting programme planned for this summer’s festival in the Scottish capital

BEN LUNN alerts us to the creeping return of philanthropy and private patronage, and suggests alternative paths to explore