GORDON PARSONS applauds a marvellous story of human ingenuity and youthful determination, well served by a large and talented company

TOM KING relishes an enlightening history of the checkered progress of the war that humanity has waged on bacteria

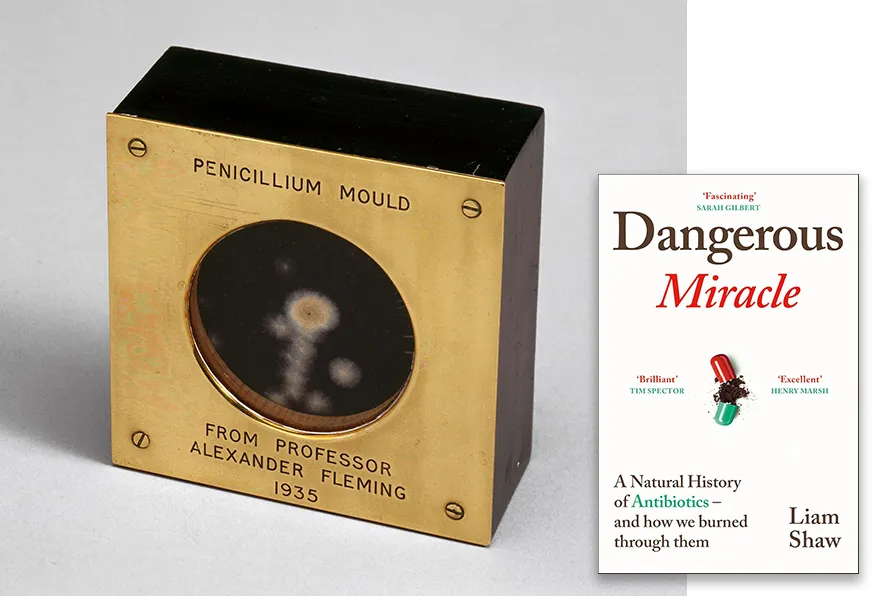

Sample of penicillin mould presented by Alexander Fleming to Douglas Macleod, 1935. [Pic: Science Museum London / Science and Society Picture Library/CC]

Sample of penicillin mould presented by Alexander Fleming to Douglas Macleod, 1935. [Pic: Science Museum London / Science and Society Picture Library/CC]

Dangerous Miracle: A natural history of antibiotics – and how we burned through them

Liam Shaw, Bodley Head, £25

ON JUNE 23 1916 a stout little submarine left Helgioland, an archipelago off the north German coast, slipping silently away from war-torn Europe towards the United States. Deutschland carried a payload of spectacular value: Salvarsan, a new arsenic compound effective against syphilis, a disease sexually transmitted as well as passed on in pregnancy, affecting one in 10 English adults at the time.

But “the arsenic that saves,” as Salvarsan became known, “wasn’t a magic bullet — it was more like a cluster bomb,” observes Liam Shaw in Dangerous Miracle. “Doctors had to inject just enough to kill bacteria without also killing the patient.”

Antibiotics are chemical weapons, deployed in a war bacteria have been waging against each other for millions of years. They are not a human invention, but a discovery. The story of their harnessing, judiciously told in Shaw’s first book, is one of hard work, dead ends, happy (and not so happy) accidents, shameless opportunism and the occasional visionary.

To 17th-century Delft we go and the home of lens-maker Antonie van Leeuwenhoek, “probably the first person ever to behold a bacterial cell” (and individual sperm — a fact Shaw curiously omits); thence to Berlin in 1884 and the hospital morgue, where Danish bacteriologist Hans Gram found pneumonia happily absorbing a rich purple dye; on to London and St Mary’s hospital in 1928, when a mysterious mould played fortunate havoc with one of Alexander Fleming’s staphylococci samples; and to Oxford in 1945, when Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin determined the structure of penicillin’s enigmatic beta-lactam ring.

If a beta-lactam ring doesn’t ring any bells, then worry not: Shaw, a contributor to this paper’s Science & Society column, is a patient and knowledgeable friend. So patient, in fact, that we go back 360 million years to a swamp before making a scenic return: through Canada’s ancient permafrost, over Arizona’s high deserts, under Ukraine’s rich, black soil and into a tuberculosis sanatorium on the outskirts of Middlesborough, glorying under the name of Grey Towers, where his grandfather received pioneering treatment as a young man.

This is a tale of astounding progress, with Salvarsan (mercifully) giving way to the more agreeable penicillin, the wonder drug which, beginning its career in humble biscuit tins, left England in a suitcase. Produced on an industrial scale in the US, it made “a triumphant return to Europe [in 1944], carried in hundreds of thousands of vials by the Allied soldiers who cascaded onto the beaches of northern France.”

The age of antibiotics had arrived — and it was a corporate bonanza. Enter Arthur Sackler, a young physician from Brooklyn “with a prodigious gift for writing advertising copy,” tasked with marketing a new drug, Terramycin.

Sackler’s master stroke was to target doctors, not patients (a noble tradition his descendants upheld when foisting OxyContin on the US, a major contributor to the opioid epidemic). He blitzed medical journals with lofty claims about this “broad-spectrum antibiotic” — coining an extremely effective phrase in the process — and promoted drug companies as “benevolent life-givers, for whom profit was a happy side-effect.”

By the 1950s, antibiotics were ubiquitous, found even in whaling harpoons as an “on-location meat preservative.” Terramycin’s maker, Pfizer, became one of the world’s largest pharmaceutical companies and the first to achieve a global revenue of $100 billion. “Capitalism had harnessed microbes,” says Shaw, and in doing so, transformed the medical profession.

But there was a catch: treatments expected to save seriously ill patients were found to be increasingly ineffective, thanks to their “widespread use for trivial ailments.” Antibiotics were exerting selective pressure on bacteria, allowing resistant strains to flourish.

Then came a terrifying discovery: bacteria in the microbiome could swap genes, acquiring resistance to drugs they hadn’t yet encountered and forging alliances over huge evolutionary distances, “as if, while drowning, you could rub up against a salmon and acquire gills.” Add to this the careless use of Colistin, “the antibiotic of last resort,” as a growth promoter on intensive farms (particularly in China, where it has fattened millions of pigs), and we appear to have a problem.

In 2024, the United Nations declared antibiotic resistance “one of the most urgent global health threats.” Over the next 40 years, it is estimated that drug-resistant infections will kill 40 million people.

Surely, the market will save us? I (don’t) hear you ask. In fact, a fascinating chapter on Plazomicin, a drug which bankrupted its developer, explains how “in a market desperate for profit, antibiotics were an appalling investment.”

The example of Bedaquiline, meanwhile, developed relatively recently against tuberculosis — which kills a million people a year, overwhelmingly in the global South — is testament to the iniquities of Big Pharma, its developer Johnson & Johnson throttling access through patent chicanery in order to make more money.

Shaw points to a solution both obvious and sadly unlikely: collaboration not for private profit, but for the public good.

Before reading Dangerous Miracle I had assumed antibiotics conformed to that familiar archetype of human folly: our insatiable thirst has dried the well and nothing can be done about it. This may be largely true, but not wholly so. More wait beyond our sight, in the warp and weft of a universe still deeply mysterious.

This remarkable book is a warning, but also a reminder: it doesn’t have to be this way.