The Bard reflects on sharing a bed, and why he wont go to Chelsea

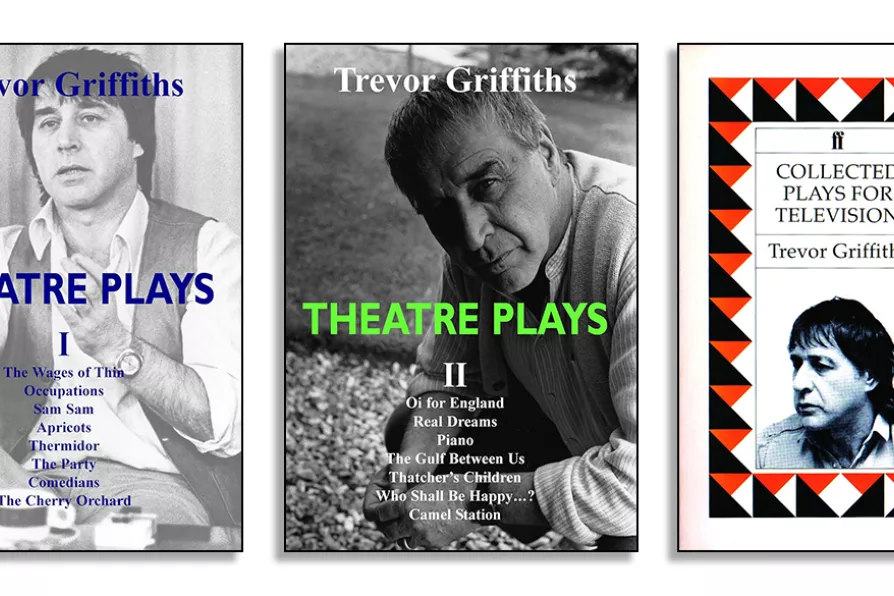

WORKING-CLASS idealist, scholar of Marx, Gramsci and Trotsky, cradle Catholic and lifelong socialist, Trevor Griffiths produced plays that managed to be deeply controversial and highly popular.

There cannot be many of us on the left, with knowledge of the English language, who have not been touched by the writer’s work. As visceral as it was erudite, his writing brought class analysis, criticism of factionalism, and profound empathy to the theatre and TV screens, from the 1960s to the present day.

LYNNE WALSH reports from the Women’s Declaration International conference on feminist struggles from Britain to the Far East

Caroline Darian, daughter of Gisele Pelicot, took part in a conversation with Afua Hirsch at London’s Royal Geographical Society. LYNNE WALSH reports

This year’s Bristol Radical History Festival focused on the persistent threats of racism, xenophobia and, of course, our radical collective resistance to it across Ireland and Britain, reports LYNNE WALSH

LYNNE WALSH previews the Bristol Radical History Conference this weekend