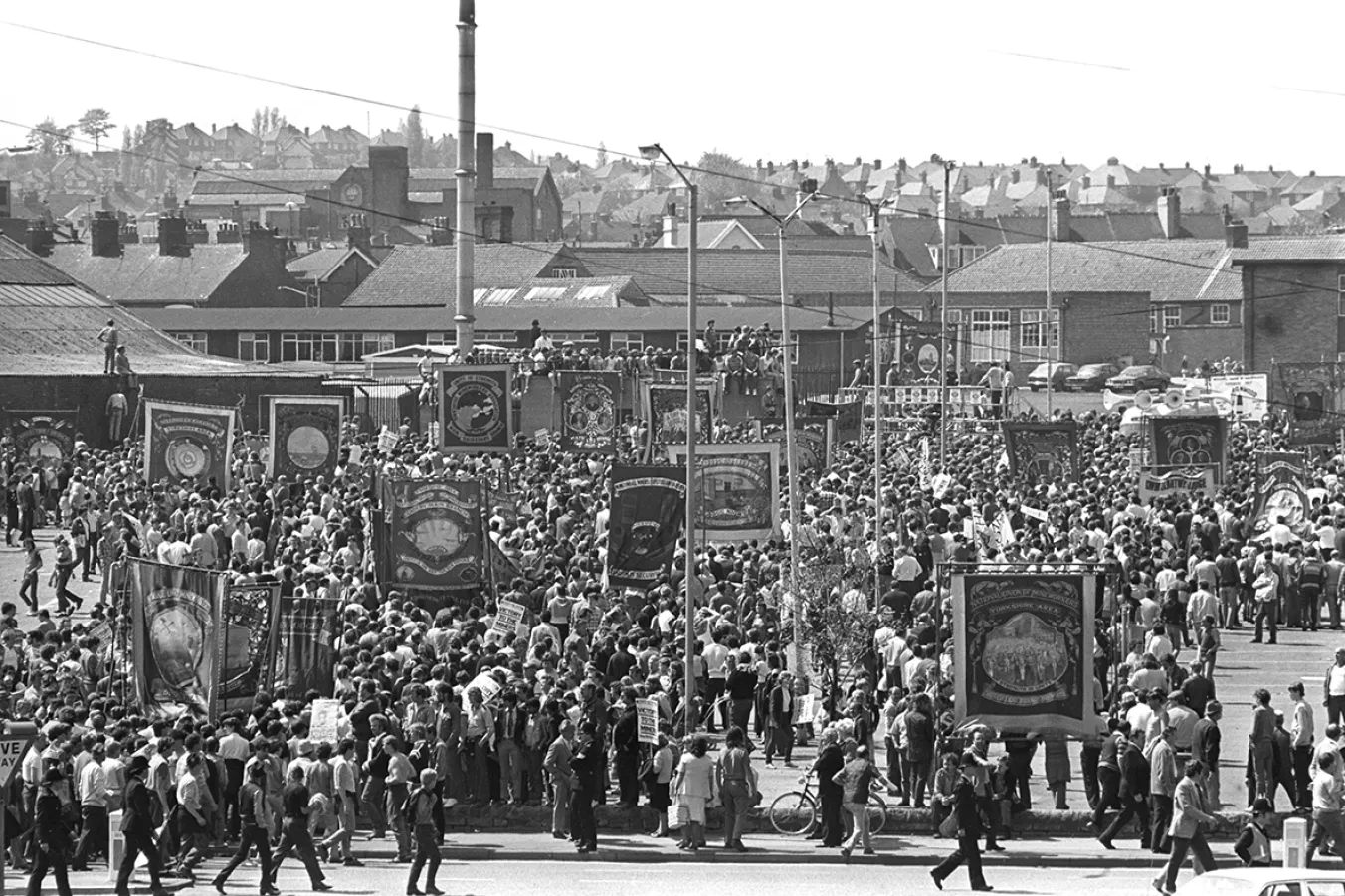

HALF a century ago, in December 1973, the Edward Heath government was advancing bullishly down a road that was to lead on February 28 1974 to a parliamentary disaster for the Conservative Party, and to a second spell of Labour government under Harold Wilson.

But in December this future was far from certain. The central issue for Heath (“the man with a boat”), against the international backcloth of the soaring price of oil and a curtailment of its supply, was the substantial improvement in wages sought by the National Union of Mineworkers for their members.

Price inflation had bitten hard into the gains made by the miners in their dramatically successful pay-catch-up strike of early 1972; and on September 12 1973, stimulated also by coal’s rising price, their claim for a new settlement was lodged.

Coal-face workers carrying out hard physical work in difficult conditions, and at high risk from dust and from pit accidents, however, were not lavishly paid.