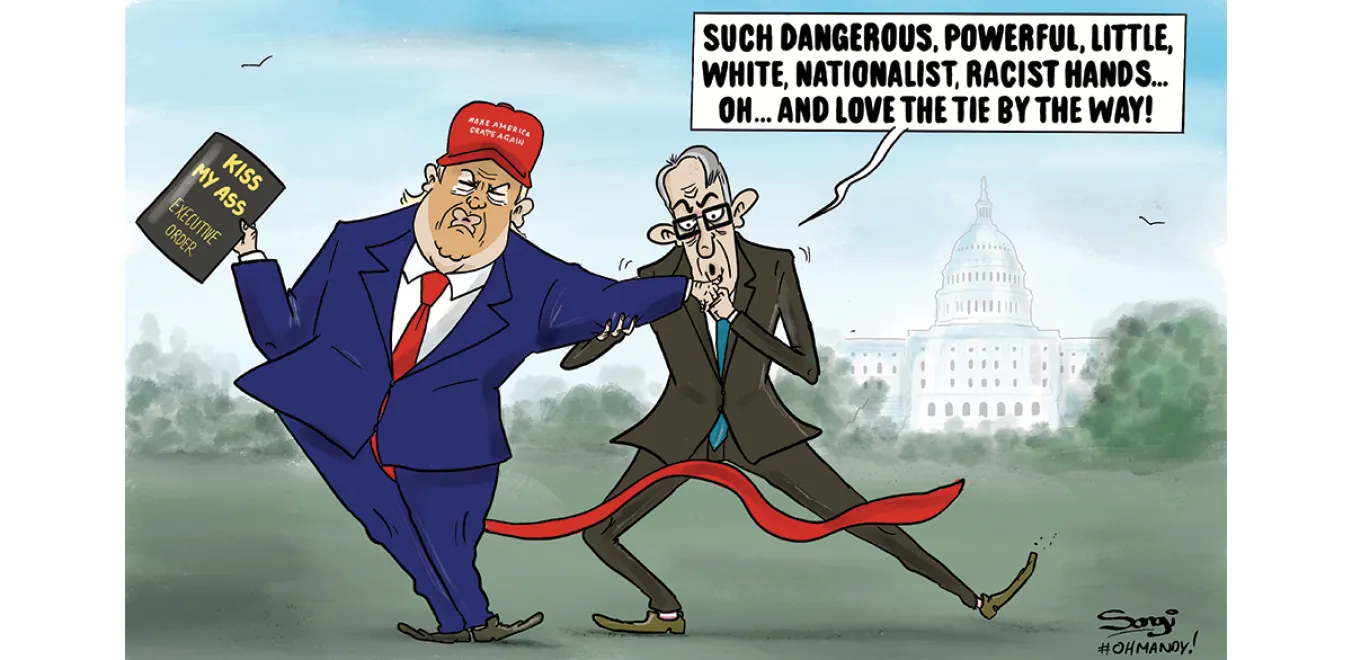

ANDREW MURRAY surveys a quaking continent whose leaders have no idea how to respond to an openly contemptuous United States

When Greek colonels staged a putch Britain looked the other way

JOHN ELLISON looks back to the 1974 general election in Greece which freed the people from the oppressive military junta

HALF a century ago, on November 17 1974, a general election took place in Greece. Former prime minister and far from socialist Konstantinos Karamanlis then returned to the premiership with more than 50 per cent of the vote.

Little publicity about the event and the outcome touched the British press, massively contrasting with the centre stage media treatment given to the turbulence in Cyprus which had given the fascist Athens’s colonels’ regime its come-uppance the previous July.

Nor was the election an occasion for bringing into greater public consciousness the terrifying seven year rule of the military junta.

More from this author

JOHN ELLISON looks back at the Wilson government’s early months, detailing how left-wing manifesto commitments were diluted, and the challenges faced by Tony Benn in implementing socialist policies

Robert Fisk and John Pilger knew that the legacy of the aggression of the US and its allies against the Middle East was crucial to understanding that crimes like the war on Gaza will only lead to more violence, writes JOHN ELLISON

JOHN ELLISON looks at the miners' strike and Shrewsbury 3 case that led Edward Heath to ask ‘Who governs Britain?’ and the electorate to answer: not you

On the 70th anniversary of the Korean armistice, JOHN ELLISON looks at a moment in time when the US almost resorted to its nuclear arsenal and Britain nearly ended up colluding

Similar stories

JOHN ELLISON looks back at the Wilson government’s early months, detailing how left-wing manifesto commitments were diluted, and the challenges faced by Tony Benn in implementing socialist policies

In a declaration from its central committee on the 50th anniversary of the twin crimes of the 1974 coup and invasion, AKEL reaffirms its commitment to a federal solution and warns against the dangers of permanent division