The Star's critic MARIA DUARTE recommends an impressive impersonation of Bob Dylan

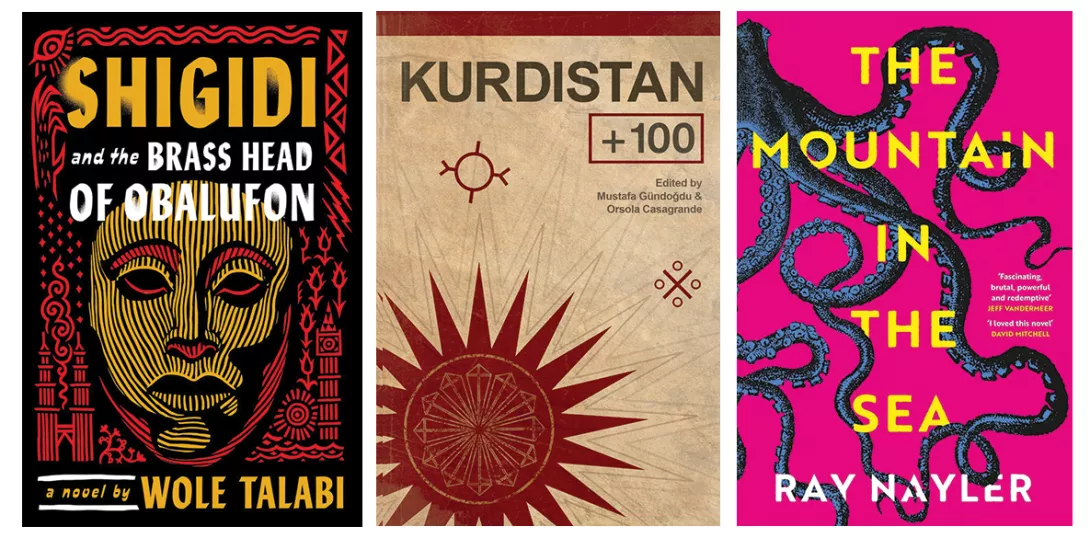

Science fiction reviews: January 29, 2024

MAT COWARD looks at the present from a new angle in order to imagine the future

EVEN gods work for the corporation, in Shigidi And The Brass Head Of Obalufon by Wole Talabi (Gollancz, £20).

For Shigidi this means scraping a living as a nightmare god on behalf of the Orisha Spirit Company, a pantheon with its roots in the Yoruba people.

His place in the company hierarchy is a miserable one, and in any case dwindling belief among the mortals means that earnings are down across the board. So when he meets Nneoma, who is a succubus among other things, he is receptive to her crazy idea of turning freelance.

More from this author

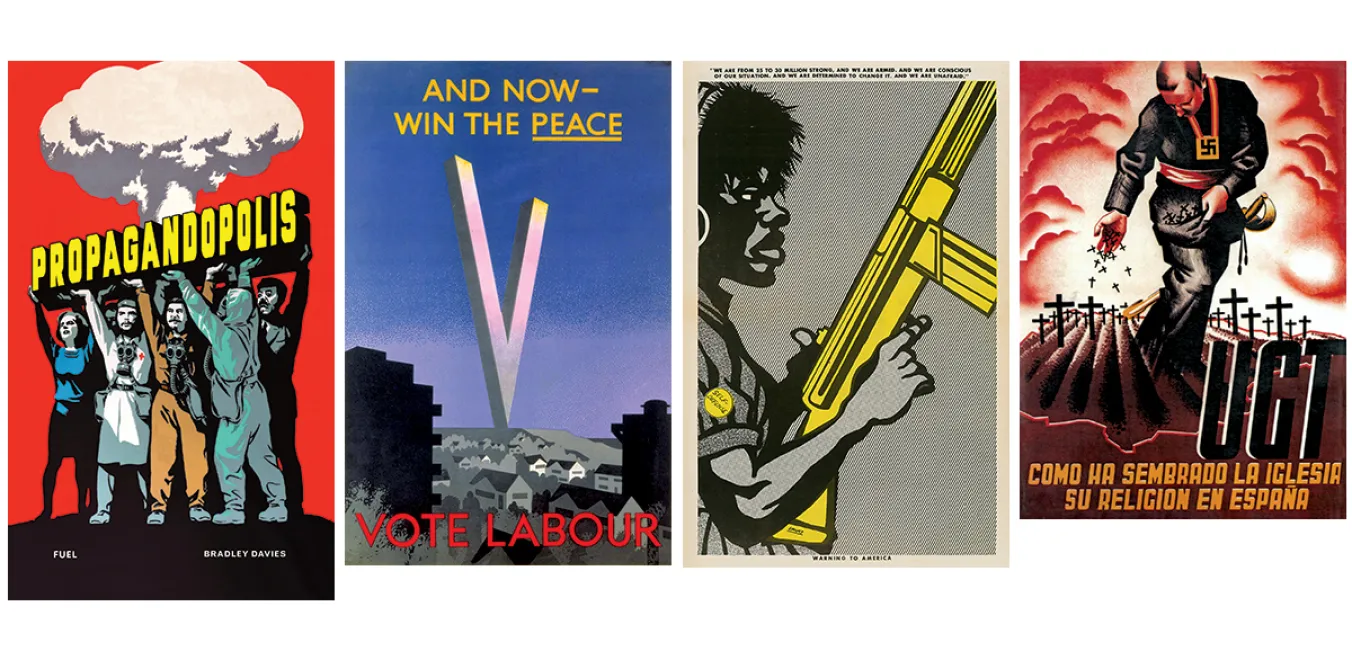

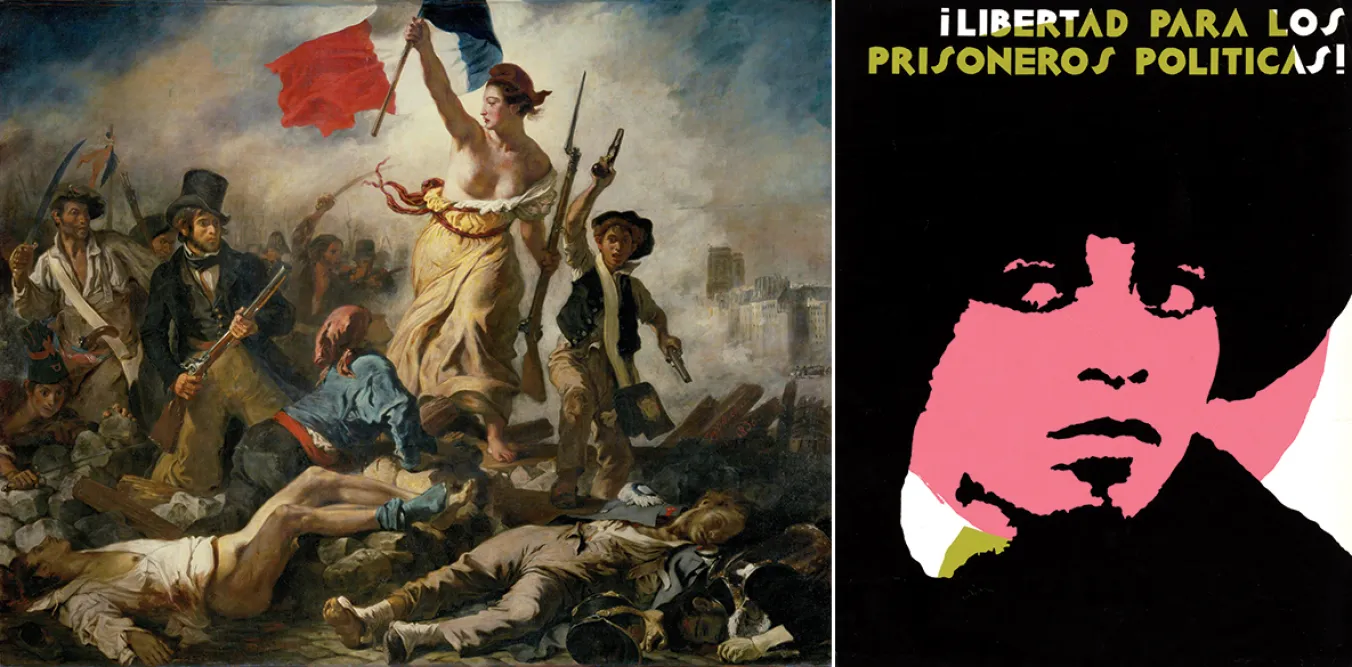

MICHAL BONCZA recommends a compact volume that charts the art of propagating ideas across the 20th century

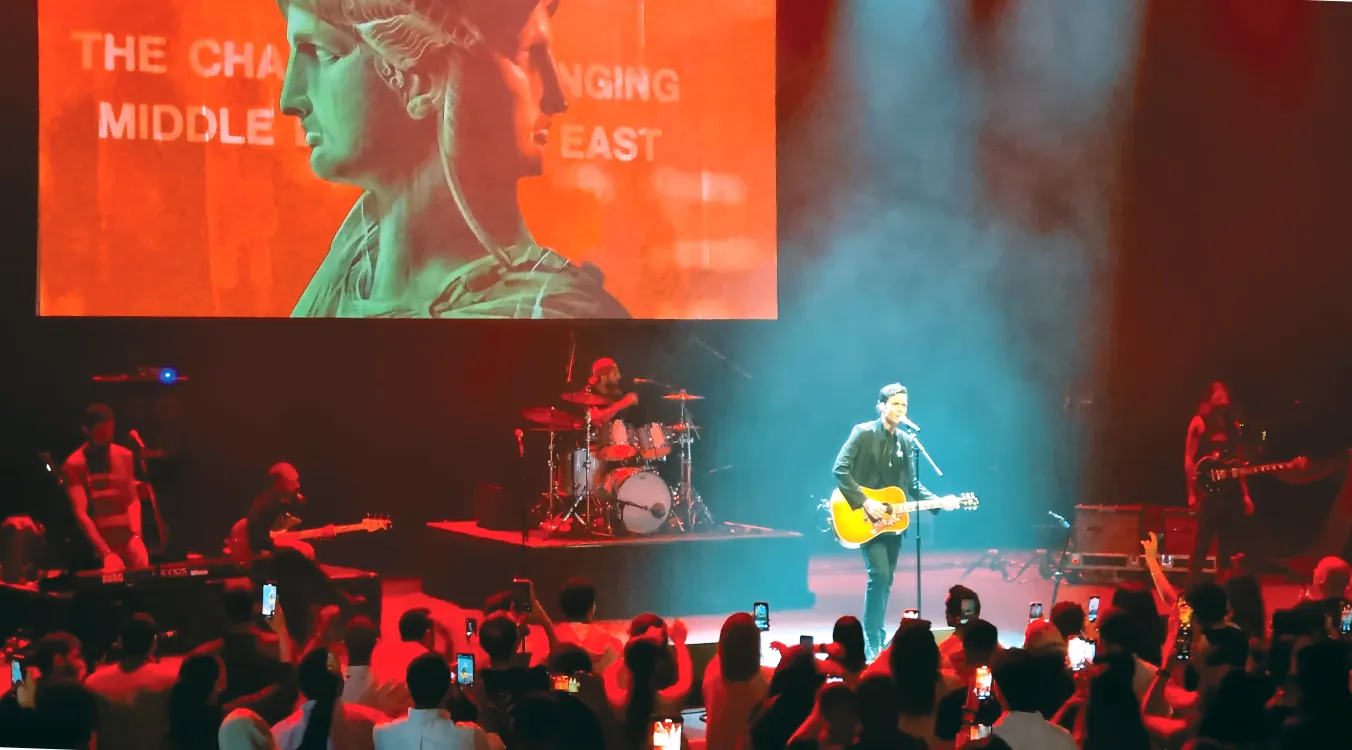

MICHAL BONCZA reviews Cairokee gig at the London Barbican

MICHAL BONCZA rounds up a series of images designed to inspire women

Similar stories

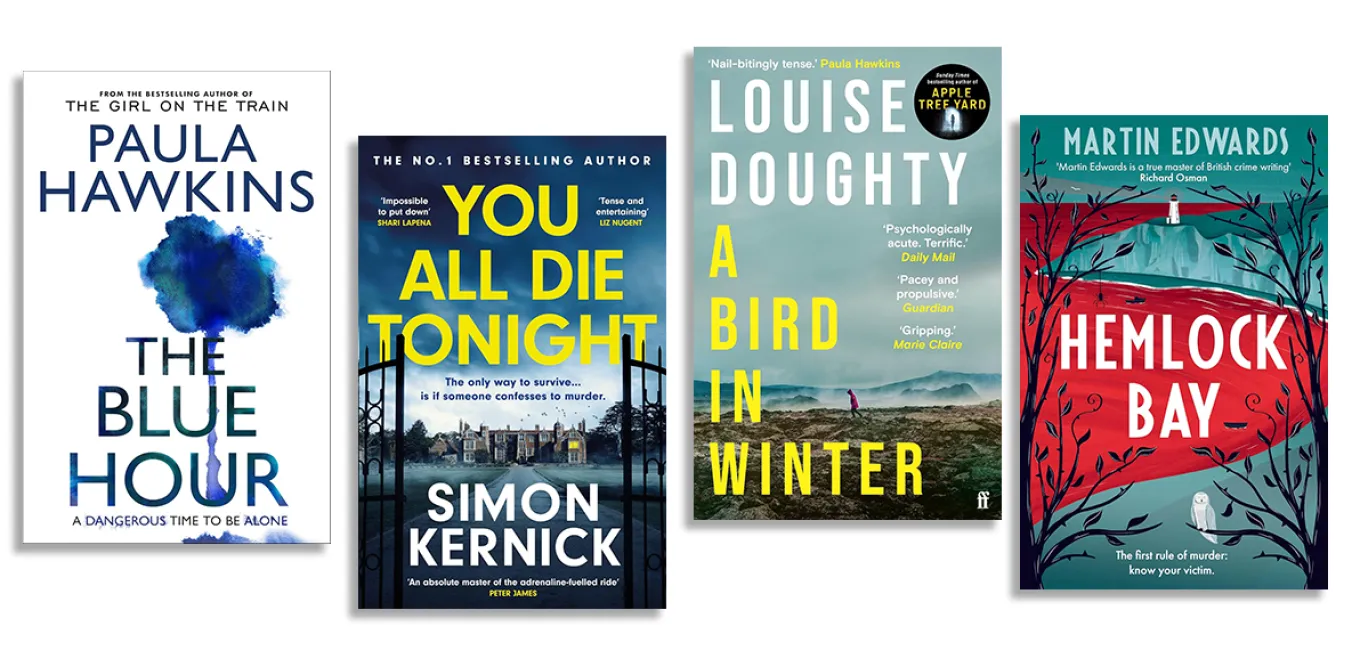

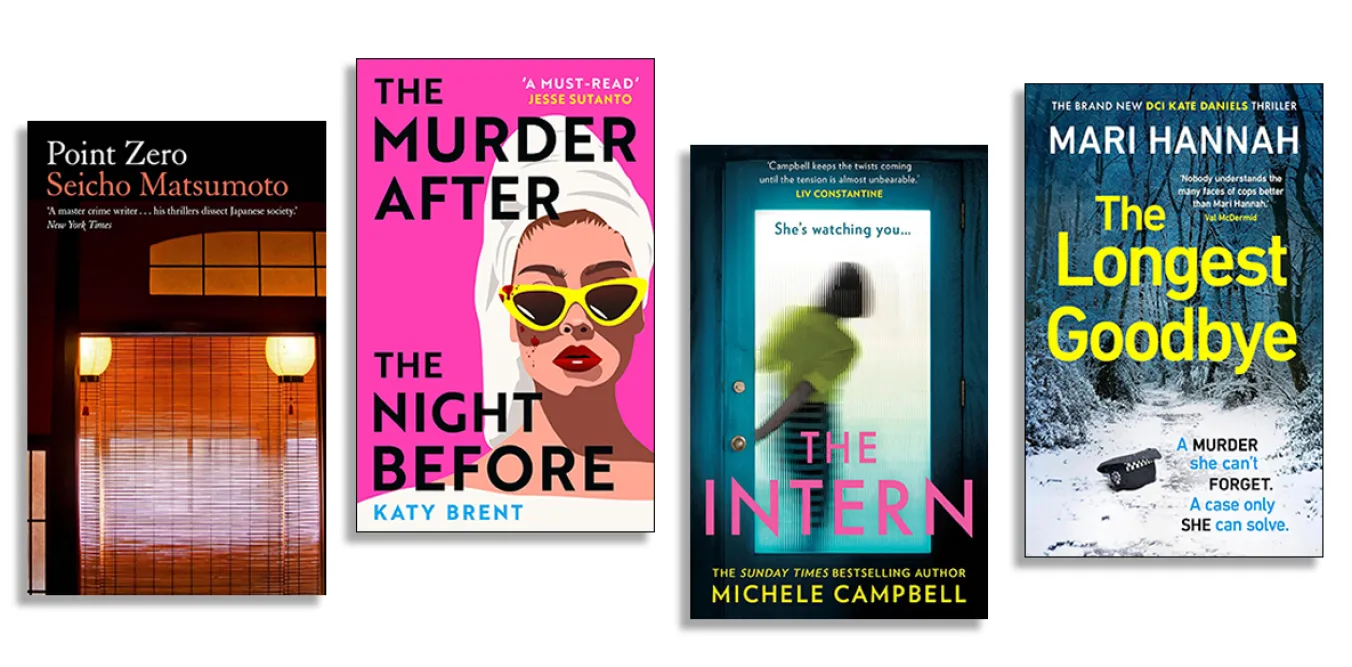

Daring Scottish gothic, a murderer in their midst, the best spy story of the year and a classic list of clues

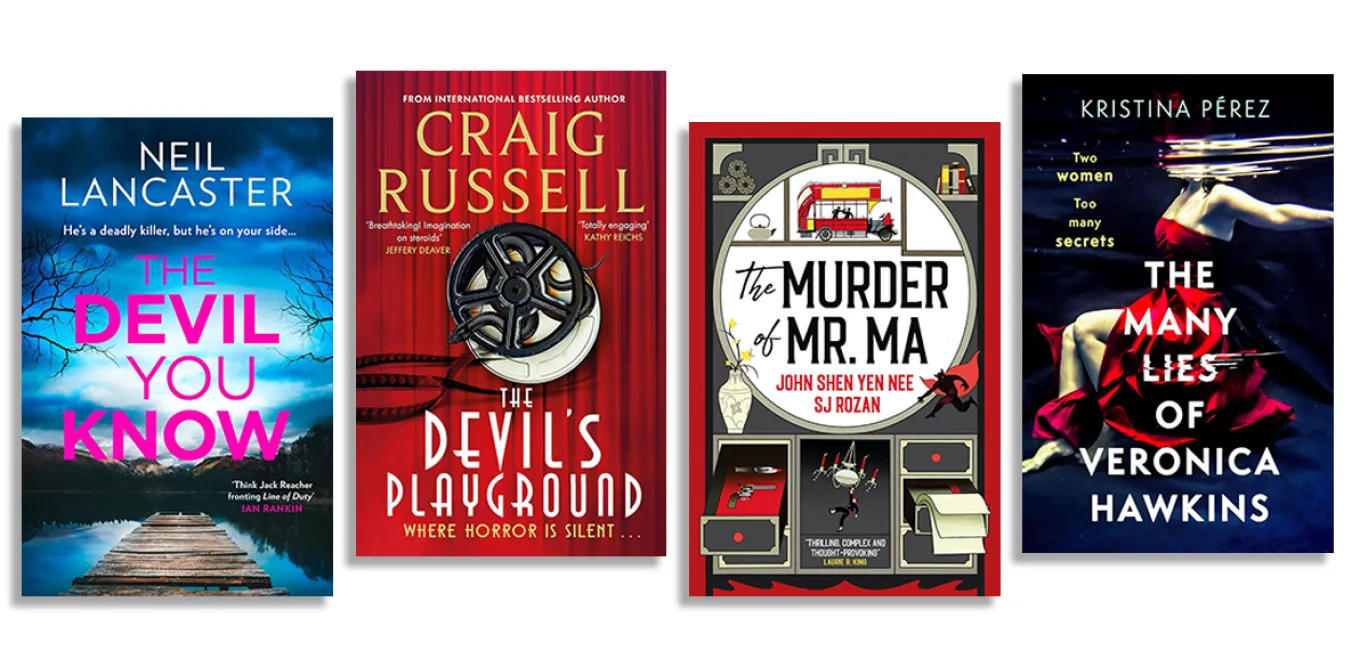

Dodgy deals in Fife, trouble in Tinseltown, London Chinese, and traps for ex-pats

Japan’s post-war secrets; a missing journalist; courtroom face-off; and a killer cop