DAVIE COOPER, a socialist, trade unionist, and one of the driving forces behind the legendary 1972 work-in at Upper Clyde Shipbuilders has died at the age of 84.

Born on the eve of the outbreak of WWII, he was raised by his wider family, including by an international brigader uncle, after the untimely death of his mother while his father fought Nazism.

In 1950s Glasgow, it is often said that as the school gates opened to let the weans out, the shipyard gates opened to let young men and women in.

That journey, familiar to thousands of his generation, was one Cooper made, leaving North Kelvinside Secondary School to take up an apprenticeship in marine engineering at then-expanding Yarrow Shipbuilders on the Clyde.

That was not the end of the journey for Cooper though. He soon made the leap from dry land onto the river itself, joining the merchant navy and travelling the world.

This would bring with it experiences which would go on to further hone his already well-developed sense of socialism, not least when he saw first-hand the realities of apartheid South Africa — and the price paid for defying it — while docked in Cape Town.

When he returned to the Govan shipyard, the boom postwar years of British shipbuilding had given way to decline and bankruptcies on the Clyde as years of underinvestment in plant and workers took their toll.

The Geddes report of 1966 recommended the formation of regional shipbuilding consortia around Britain and by 1968 — under the watchful eye of then minister for technology Tony Benn — Upper Clyde Shipbuilders (UCS) was formed to deliver the economies of scale thought to be needed to save the industry.

In return for a 48 per cent stake, the Labour government provided millions of pounds in interest-free loans to retool the industry for survival, but by 1971 — despite a healthy order book — UCS was plunged into crisis when the profit-making Yarrow Shipbuilders left the consortium and a new government turned its back on the industry.

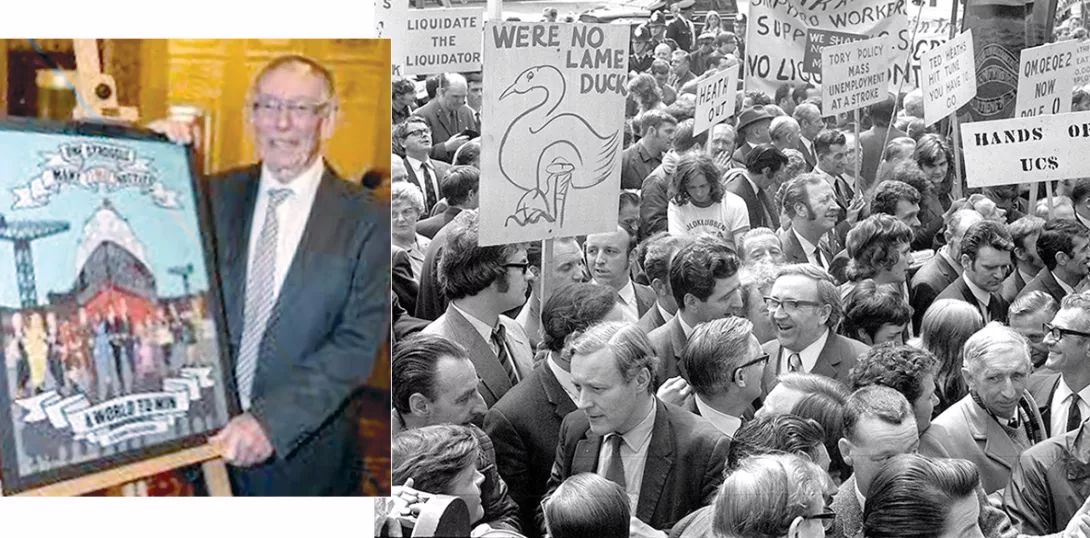

The new Tory government, led by Edward Heath and under the influence of free-marketeers in the Selsdon Group, made clear that they would no longer provide state backing for what it branded “lame duck” industries and refused pleas from the UCS for emergency working capital to allow it to complete its orders.

That decision could have been the end of the story for the Clyde shipbuilding industry, once the heart of the whole British industry and which had built more than 40 per cent of world tonnage by the first world war.

The Tories had not, however, reckoned with the organisational genius, the skill and the creativity of the working people of Glasgow, the working people of the yards, and the joint stewards at UCS.

What followed has become the stuff of legend. Stewards, many of whom — like Davie Cooper — had received a political education in, and were members of, the Communist Party, chose not to fight for the right to work by strike action, but instead by taking over the yards to complete the order book in what became known as the “work-in.”

Support — moral and financial — trickled in from across the city, growing across Scotland, across Britain, until finally a flood of solidarity from across the world sustained their battle against Heath and for the dignity of work.

Cheques arrived from Soviet shipyard workers, and £5,000 and a bunch of flowers from John Lennon and Yoko Ono were reportedly greeted by the cry “But Lenin’s deid,” while gigs and socials were held across Scotland to build support even further.

It took more than just cash, solidarity and moral support from the outside to sustain the action however, it took discipline, and while Jimmy Reid’s oft-quoted “no bevying” speech warning workers that the eyes of the world were upon them took the headlines, the less publicised, calm, clear and firm speeches to comrades from Cooper were crucial to maintaining support and organisation in the heart of the yards.

The sight of the workers of the Clyde fighting to build ships while the prime minister raced his yacht only brought the class conflict at the heart of the battle into further contrast, and after a year of hard work Heath finally capitulated and UCS was awarded a £35 million government grant.

Cooper later commented: “The government knew it was defeated although it fought on for another six months, and then sought to gain credit for the settlement that preserved all four yards.”

Cooper continued to work at the yard, through the nationalisation, privatisation, and changes of ownership that were to come, before a long retirement filled with books alongside his wife of more than 40 years, Ann, and their oil rig worker son, David, who survive him.

He and his fellow UCS work-in veterans leave another legacy though, one that they shared at its 50th-anniversary celebration at the Glasgow City Chambers less than two years ago — an example of where the power really lies in the world and a challenge to the next generation to realise it.

As Cooper said himself: “It was working-class solidarity, nothing else, that saved the yards” — a lesson to us all.

Davie Cooper, socialist, trade unionist and UCS veteran, born on July 15, 1939, died of sepsis on January 26, 2024, aged 84.