THE defeat of the miners’ strike was so profound that even after 40 years, its impacts are still unfolding. In 1984, there were 170 coalmines in Britain; 20 years later, there were just 13. After the defeat, miners’ communities faced a unique combination of concentrated joblessness, physical isolation, poor infrastructure and severe health problems.

Setting the strike in a long view, looking both before and after, we can see that the defeat of the miners changed the trajectory of justice in Britain: what justice means, who can claim it and how. With the loss of the miners’ jobs and communities, we also surrendered collective responsibility for social and industrial justice.

In this long view, I’m going back to the 1919 Treaty of Versailles, an agreement to which Britain was a principal author. It proclaimed: “Peace can be established only if it is based upon social justice,” and it stated that signatory nations, moved by “sentiments of justice and humanity” now recognised that “the well-being: physical, moral and intellectual, of industrial wage-earners” was a matter of “supreme international importance.”

Through the treaty, the nations committed to creating a permanent machinery for industrial justice through which “labour should not be regarded merely as a commodity or article of commerce.” This machinery of industrial justice would protect “the right of association for all lawful purposes by the employed … to confer lasting benefits upon the wage-earners of the world.” The appeal to social justice at the end of the first world war was a social and industrial justice — indeed it was a class justice.

Now fast-forward to 1944, at a point when the end of the second world war was in sight. The international community reached a new agreement in the Declaration of Philadelphia, reaffirming those principles of collective responsibility for social and industrial justice.

Once again, freedom of association was recognised as “essential” to human progress, repeating that “labour is not a commodity” and assuring the right of “all human beings to pursue their material well-being in conditions of dignity and freedom.” Significantly, the Declaration of Philadelphia detailed freedom of association as a right that gave trade unions equal status with government and with employers, to join with them in free discussion and democratic decision-making.

The right of association is the basis of collective social and industrial justice, and it is set out in Conventions 87 and 98 of the International Labour Organisation, ratified by Britain in 1949 and 1950. The right of association is assured in the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), ratified by Britain in 1951, and through judgements of the ECHR.

The machinery of collective justice afforded by the right of association includes the right to organise in trade unions, to represent our interests collectively, a right to be represented collectively, a right to be able to negotiate and bargain collectively, and a right to strike. These collective rights are the legacy of two world wars and provide formal recognition of the collectivism of social and industrial justice.

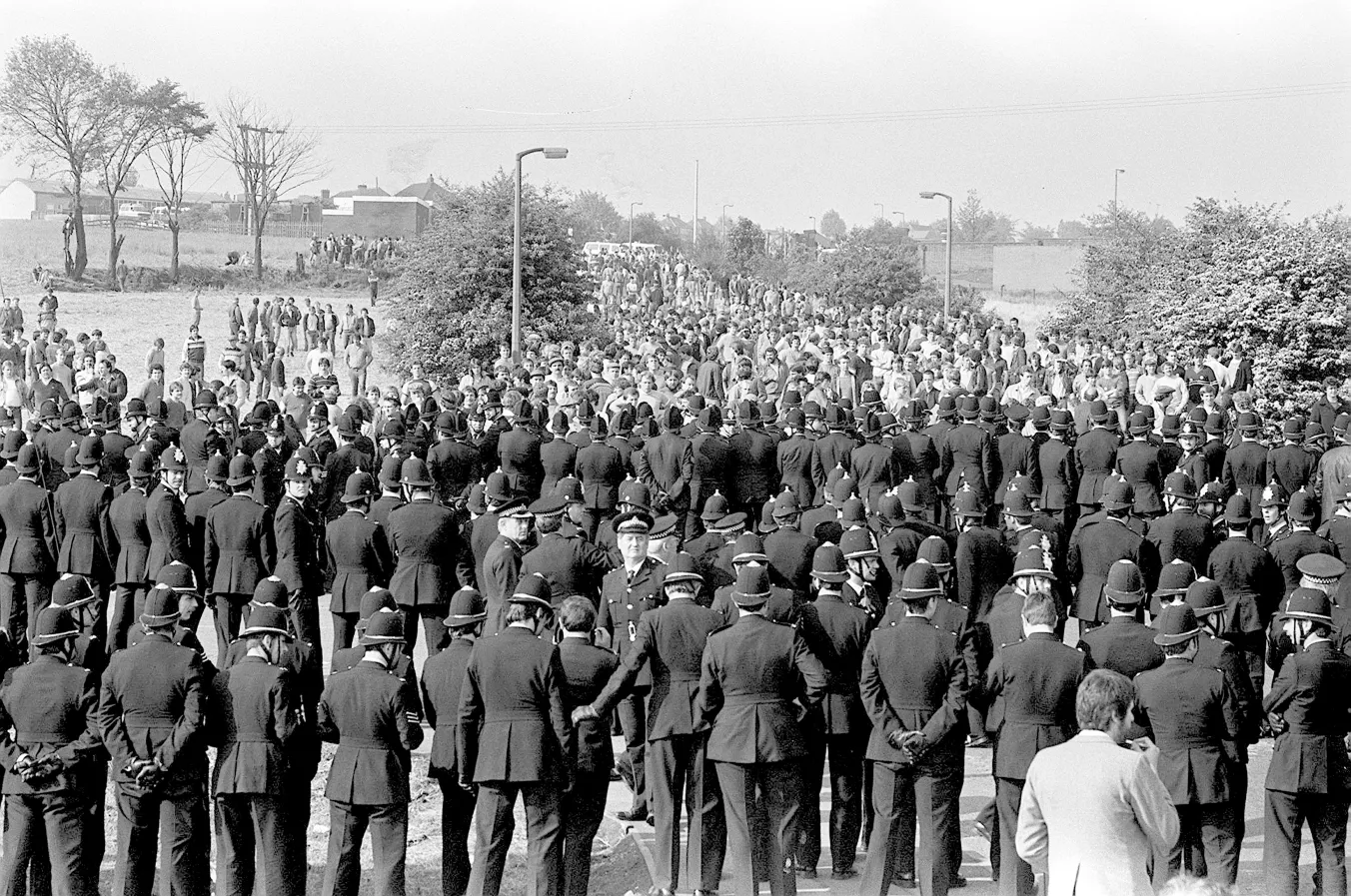

Welsh philosopher Raymond Williams saw the early 1980s as a period in which “the most open class struggle British society had seen since the war” resulted in the defeat of the miners. The apparatus of the state hit the miners so hard that, by the end of the strike, all the unions knew that concerted action anywhere to protect jobs or pursue wages would invite the same ruthless treatment.

Arthur Scargill, when campaigning in 1981 for election to lead the National Union of Miners, observed: “The coal industry and British miners are at the centre of a political maelstrom.” Indeed, the defeat of the miners both symbolised and precipitated a defeat of the class by the state. In that defeat, we lost collective responsibility for social and industrial justice.

Through successive Acts of Parliament designed to restrict protest and weaken trade unions, the Conservative government took union decision-making out of the workplace, stopped workers from acting together in solidarity, criminalised aspects of picketing or protest, and further restricted industrial action.

Hand in hand with the dismantling of our collective mechanisms for securing justice, they dismantled social and public infrastructure, social security and welfare; they imperilled the health service, schools, and British manufacturing industry.

The unions campaigned for the repeal of anti-trade union laws. However, by the time of Labour’s electoral victory in 1997, the trade union movement was assumed to be so weakened that it would accept Labour’s incarnation of parliamentary representation as a substitute for the restoration of collective responsibility for social and industrial justice.

Parliamentary representation through the Labour Party in government delivered reinvestment in public services via private finance initiatives, student fees and corporate sponsorship of schools. It redesigned public services via the power of competition, increased choice and best value. It re-engineered accountability of “them, the elected” to “us, the people,” via arms-length regulatory bodies and quasi-public non-governmental organisations.

It diversified social security provision through the engagement of the third sector, charities and faith organisations together with the introduction of a new welfare contract with wider use of benefit sanctions. It made promises of regeneration and good quality work to ex-industrial communities devoid of jobs by relying on a smoke screen of inward investment and public-private partnership.

And all the while, the Labour government was also plugging the gaps of justice at work by creating individual employment rights. The Labour years not only failed to repeal the anti-union laws, but they also gave rise to an era of individual employment rights in which every worker could supposedly benefit from a special status as right-holders at work.

The Labour years changed the parameters of social and industrial justice. They shackled the reach of our expectations to matters of procedural fairness, equality of treatment, and the removal of discrimination in decision-making.

They gave us individual rights through which we could appeal to the judicial arm of the state to acknowledge the harms of wrongs that had already occurred: dismissals that had already happened, consultations that had not taken place, maternity pay not provided.

All looking backwards, all serving as a limit to our reasonable expectations. None offering the machinery of collective responsibility for social and industrial justice through which workers could have a voice and choice to expect any better.

The promise of individual rights under Labour quickly turned sour once the Labour government fell in 2010. With the Conservative Party back in power, the mechanisms through which individual rights could be secured were under sustained attack.

The Legal Aid Sentencing and Punishment of Offenders Act 2012 removed legal aid from almost all welfare and employment cases. The volume of such cases supported by legal aid fell by 99 per cent within a year and legal aid has never returned. Workers lost access to free legal representation, the costs were shifted onto their shoulders and those of their unions.

In 2013, fees to access the employment tribunals were introduced through new regulations. The volume of claims fell by 70-80 per cent in employment and workplace discrimination matters. Of course, there had been no reduction in the volume of abuse of workers’ rights. Workers continued to have their wages unlawfully deducted, their pay set by sex discrimination, and their jobs ended unlawfully, but from 2013, workers had lost the ability to have the matters heard in law unless they could pay.

Importantly, Unison took the government to court over employment tribunal fees. In Unison v Lord Chancellor [2017] the Supreme Court agreed that preventing workplace rights from being enforced left little prospect of employment law being respected at all.

The regime of fees constituted an unlawful breach of our fundamental, constitutional right of access to a court. In the Unison decision, the judges explained that access to justice was not an individual quest built on individual rights, but a collective matter of public interest that underpinned the functioning of a democratic society.

Democracy depends on our access to justice. Yet since the lifting of employment tribunal fees, the volume of claims to tribunals has never recovered. One reason is the slashing of funding for the operation of the courts and tribunals. In 2023, the average wait for a first-instance employment tribunal hearing was 18 months.

The lack of respect for workers’ access to justice as individuals demonstrates there is no political consensus in Britain about the right to have rights in an industrial context. Yet, the Labour government’s failure to restore collective mechanisms for justice was taken by the ECHR as evidence of a “democratic consensus” for heavy restrictions in Britain on freedom of association. In the case of RMT v UK [2014] the ECHR characterised British law on strikes and freedom of association as being “at the most restrictive end of a spectrum of national regulatory approaches.”

Yet the ECHR would not declare Britain’s blanket ban on secondary industrial action to be “manifestly without reasonable foundation,” in large part because the consecutive Labour governments of Tony Blair and Gordon Brown had not acted to defend collective responsibility for industrial justice.

Emboldened by the idea of a reasonable political consensus on restricting freedom of association, the Conservatives introduced the Trade Union Act 2016. This further increased opportunities for employers to challenge the legality of industrial action ballots, strengthened employers’ ability to prepare to withstand strikes and subjected workers in public services to the most restrictive of balloting thresholds.

In respect of entitlement to individual rights, there was a notable victory in Uber v Aslam [2021], when taxi drivers were recognised as having worker status. However elsewhere, the Supreme Court rejected arguments in favour of statutory minimum terms and conditions by failing to recognise workers as a class.

Despite appallingly low pay, known exploitation and instances of modern slavery, care workers as a class lost the protection of the national minimum wage law for “sleep-in shifts” in the case of Mencap v Tomlinson Blake [2021]. In December 2023, the Supreme Court denied Deliveroo riders access to collective union representation at work. Once again in the context of appallingly low pay, known exploitation and instances of modern slavery, workers were excluded from legal protection.

For Deliveroo riders, this meant the right to freedom of association under the European Convention on Human Rights was denied. Why? because the court would not recognise the riders collectively as workers, they were merely individuals.

Arguably the most prominent examples of the absence of social and industrial justice in Britain since the miners’ strike lie in the scale of unnecessary deaths, life-changing illnesses and lost jobs due to the Covid pandemic.

Now four years on, it’s widely accepted that workers have individual employment rights they cannot access; that record numbers of workers are too poor to afford nutritious and appropriate food; that Britain has record numbers of zero hours and insecure contracts; that there are more working people known to be in ill-health and experiencing disability than ever before.

The chair of the Bar Council drew attention in February 2024 to the threat to the international reputation of England and Wales because of failures in justice. These are failures in the functioning of a democratic society.

At the time of the miners’ strike in 1984, people feared unemployment, Today, people fear unemployment and work because work is too frequently low-paid and cripplingly insecure. They fear work and they cannot shape decent jobs for the future because our collective machinery has never been repaired after the reorganisation of the relations between workers, employers, and the state. Because of the miners’ strike.

The defeat of the miners was so significant because the workers lost to the state, that’s why the anti-union laws have never been repealed. The defeat of the miners transformed the use of law; the design of social and industrial justice; the substance of justice; what it entails, who can get it and how it can be secured.

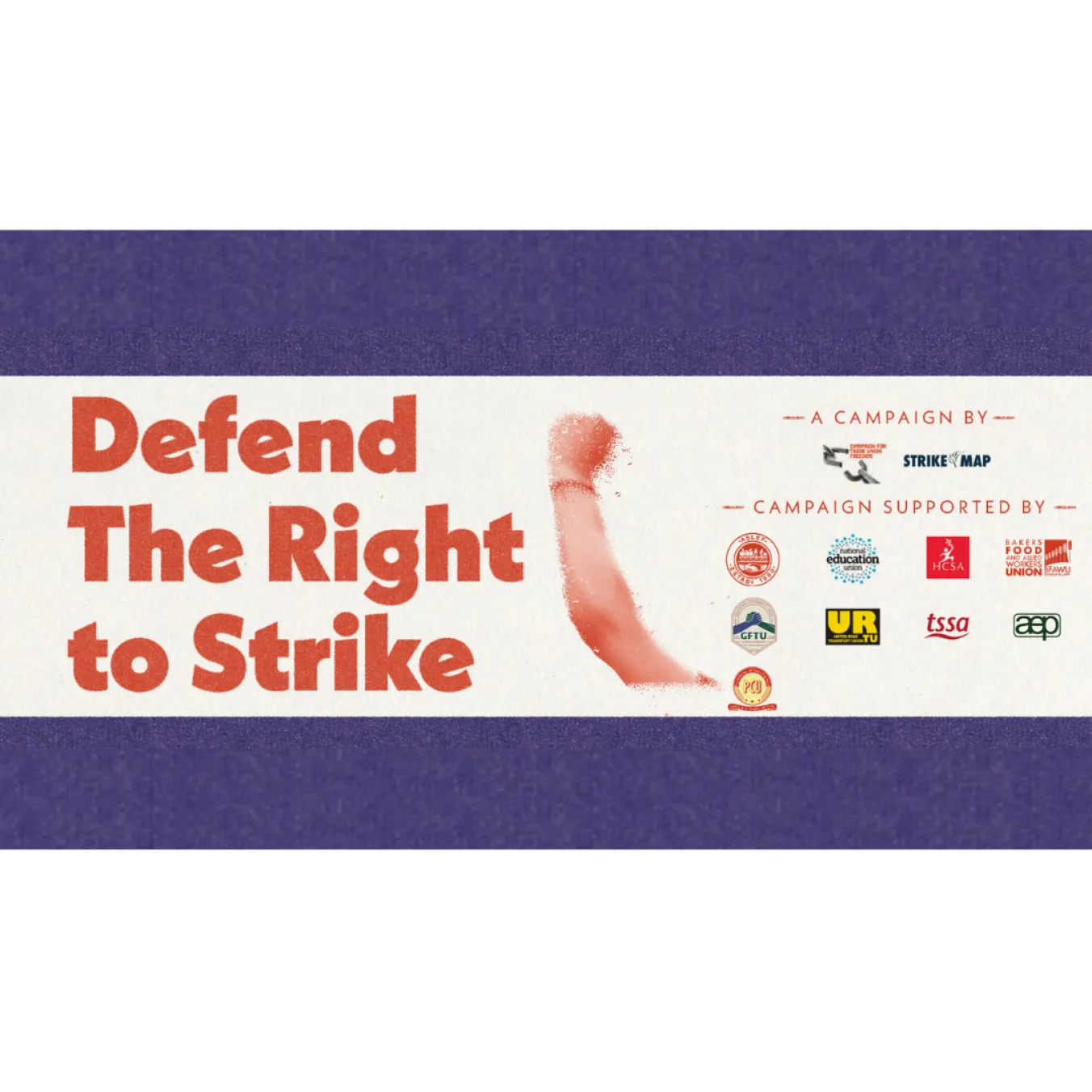

Now, at a time when the freedom of association is most required, trade unions are being assaulted in law once again: a new regime of fines can be imposed by the certification officer; the further shutting down of protests; the Strikes (Minimum Service Levels) Act 2023.

And so it continues. The regulations that enabled employers to hire agency workers to break strikes were quashed in the courts on procedural grounds in August 2023, and yet in November of last year, the government opened a consultation on its intention to reintroduce strike-breaking by agency workers. Further, in February 2024, the government opened a consultation on its intention to re-introduce fees to access employment tribunals.

Industrial and social justice may be understood to be in crisis: no longer fit for protecting workers. In 1984, a majority of people in poverty were in households with no work. Today well over 60 per cent of those in poverty are in households with work.

Work is not paying, and this problem is down to the absence of social and industrial justice that has followed on from the miners’ strike. There are many legacies of the defeat of the miners. One is that it changed the trajectory of justice, what it means, who can claim it and how.

Yet in the words of the writer and poet Maya Angelou, experiencing defeat does not mean we are defeated. It is part of the legacy of the miners’ strike that we must reassert the fundamental necessity of collective machinery for social and industrial justice.