Recent research pushes back the date of the earliest cave art by several thousand years. ROX MIDDLETON, LIAM SHAW and MIRIAM GAUNTLETT look into the science applied

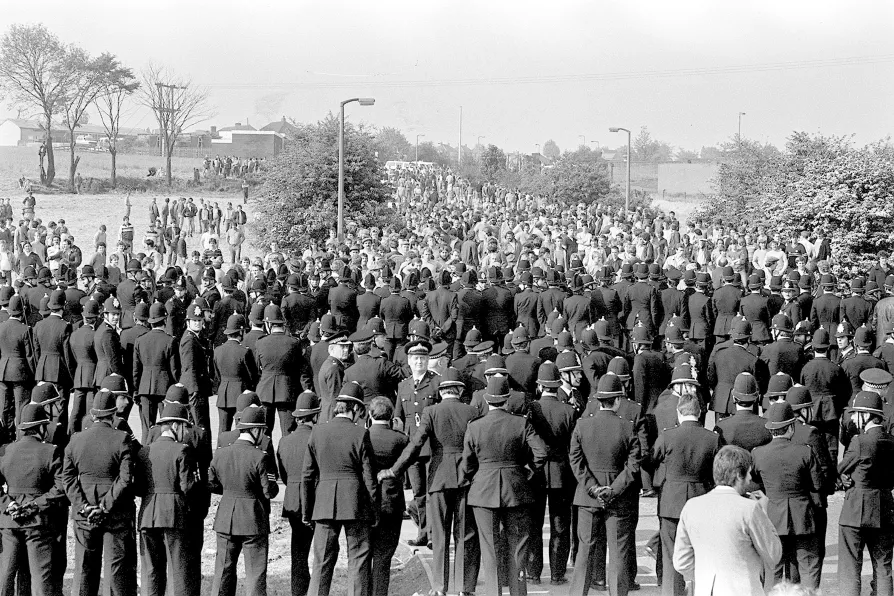

THE STATE vs THE PEOPLE: Massive police presence greets pickets as they arrive on the hill heading to the Orgreave Coking Plant near Rotherham during the miners disputes

THE STATE vs THE PEOPLE: Massive police presence greets pickets as they arrive on the hill heading to the Orgreave Coking Plant near Rotherham during the miners disputes

AS we commemorate the 40th anniversary of the 1984/85 miners’ strike I remember the feeling of excitement I had as a 17-year-old miner at the start of the strike — excitement at doing something different from what had become the norm, giving my support to fellow miners whose jobs were under threat.

A lot was said at the time and over the years since the strike, about if there should have been a ballot to legalise the strike. As a 17-year-old at the time the ballot question never made any sense to me. We were part of a trade union. The purpose of the trade union was to collectively organise everyone and support each other when in need.

We had been asked by fellow miners whose pits were being threatened by closure and were facing losing their jobs for our support. There was no need for a ballot. We were obliged to give them our support as we would have expected them to support us had the roles been reversed.

Listening to my more experienced workmates who had taken part in the strikes of 1972-74 it was expected to be “a long strike,” maybe six to eight weeks. Some were even talking about it lasting up to or even over the summer as the National Coal Board (NCB) had been preparing to take us on and the timing was not on our side. No-one expected it to last 12 months, no-one knew the extent of the planning and preparation that had been done by not only the NCB but by the government.

There was some debate about the timing of the strike at the time and there has been much more since. Should we have waited until the autumn when the demand for coal would have been higher?

How could we have delayed going on strike? How many pits would have closed and fellow miners lost their jobs before the timing was in our favour? You could not justify holding off as there would never have been a right time to go on strike and as more pits were closed and fellow miners lost their jobs it would have been harder to draw a line in the sand and make a stand.

At the start of the strike, there was a feeling that this was bigger than an industrial dispute between employees and employers, a feeling that intensified as the strike went on and with good justification.

As a flying picket, I picketed in Lancashire, Nottinghamshire and north Wales. At the start of the strike, there was a police presence on the picket lines but nothing like it ended up being towards the end.

Who would have thought there would have been police roadblocks on the exits from the motorways, checking for pickets and turning us around? Having to take the back roads and service roads in a game of cat and mouse with the police to get to the picket lines?

That tactic changed at Orgreave where the police roadblocks were still there but they were not trying to turn us back, they were giving us directions where to go, or more accurately where they wanted us.

The excuse that the police were trying to limit the number of pickets getting to the picket line in large numbers fearing a breach of the peace didn’t apply at Orgreave. They wanted us there in large numbers.

There is no doubt in my mind that there was a plan to incite a riot at Orgreave on June 18 1984. But it was not the ones who were turning up in T-shirts, jeans and trainers who were planning a riot.

It was the ones who turned up in body armour with riot shields and truncheons and supported by the mounted police and K-9 units. How can it be possible that this was allowed to happen unless it was sanctioned from the very top?

It is an injustice that there has never been an inquiry into the policing at Orgreave. While Orgreave was a well-documented event with the press and media there the tactics used by the police that day were used on picket lines and in mining communities up and down the country throughout the strike.

Maybe that is what the Tory government are afraid of, that an inquiry into the policing at Orgreave would expand into an inquiry of the policing of the whole of the strike.

When she was home secretary Amber Rudd MP refused an inquiry into Orgreave on the basis that “no-one died.” Well that was more down to luck than judgement as some of the injuries to pickets on that day were horrific and life-threatening.

“No-one went to prison,” she said. That was because, at the start of the first batch of cases for riot, it became clear that every police officer who took the stand was committing perjury, an offence that no police officer was ever charged with. That would not have happened had it been us lying under oath.

“It was a long time ago,” said Amber Rudd. There should be no time limit on justice. “The police had changed over the years.” Well, that is open to debate.

While Rudd was right about no-one dying at Orgreave she dismissed the fact that people did die during the strike on and off the picket lines, including Yorkshire miners Davy Jones and Joe Green whose lives we commemorate at our Memorial Lecture today.

People did go to prison and — as the Scottish government inquiry has shown — on trumped-up charges. There was then and there still is now a justifiable case for an inquiry into the policing at Orgreave and the whole of the strike.

Who was responsible for instigating the police riot? On whose instruction? Why were police officers compelled to be complicit and stay quiet about it?

These questions must be answered not just to get justice for those who were there but to ensure safeguards can be put in place to ensure what happened back then can never happen again, to ensure that the police cannot be used as a paramilitary force against the public to push a political objective.

While the pit closure programme has decimated many mining communities the half-hearted attempts at regeneration have not replaced the jobs lost like for like. Many of the jobs are low-paid, insecure and un-unionised warehouse jobs. To add insult to injury many of the former pit sites have been developed into housing estates with houses that are unaffordable to local people working in the warehouses.

They may have destroyed the mining communities but as this year will show with the many local anniversary events being organised they have not destroyed the community spirit.

There is also the continuation of collective punishment of former miners, their families and communities introduced at the time the remaining pits were privatised when the Mineworkers Pension Scheme (MPS) was closed and guaranteed by the government which would underwrite any losses.

The government has taken £4.7 billion from the scheme but has never had to pay a penny piece into it under its guarantee.

If nothing changes it will take at least £1.4 billion more from the scheme’s Investment Reserve surpluses and tens of millions more from past surpluses.

It cannot be right that any government should make billions of pounds’ profit from providing a guarantee that has never been called upon. The funds of the MPS should be used to improve pensions for the people who paid into it over their working lives, improving pensions so that they can enjoy a retirement that they worked hard for, look after their families, and spend in their local communities.

Recognition should be given to the trade unions and individuals who supported us during the strike and it should never be underestimated including the invaluable support from the Women Against Pit Closures movement, without who we would never have been able to sustain the strike for as long as we did.

Hopefully, with a change of government, we will get an inquiry into the policing at Orgreave and the whole strike. We can then get closure and start to move on. We will end the injustice of the MPS government guarantee and the funds in the scheme will be used to improve pensions.

I am proud that I supported fellow miners when asked and stayed out until the end, fighting to retain jobs, our industry, our communities — in short, our way of life.

Every miner who supported the strike in 1984-85 can rightly hold his head up high and be proud of the fact that we stood firm, side by side.