Recognising the humanity of Ethiopia

An encounter with a cabbie has ROGER McKENZIE reflecting on the remarkable history of a great African nation and the importance of migrants and their skills for our beloved NHS

AFTER the relief of finally tracking down a taxi that would take a debit card on a hectic Saturday night near Cardiff railway station, my wife and I got chatting with the driver.

The driver, who was willing to take us back to our hotel by a convenient cash point, originally hailed from Ethiopia and, it turned out, knew our home town of Oxford because he had trained there as a radiologist.

There is so much to unpick from that one sentence.

More from this author

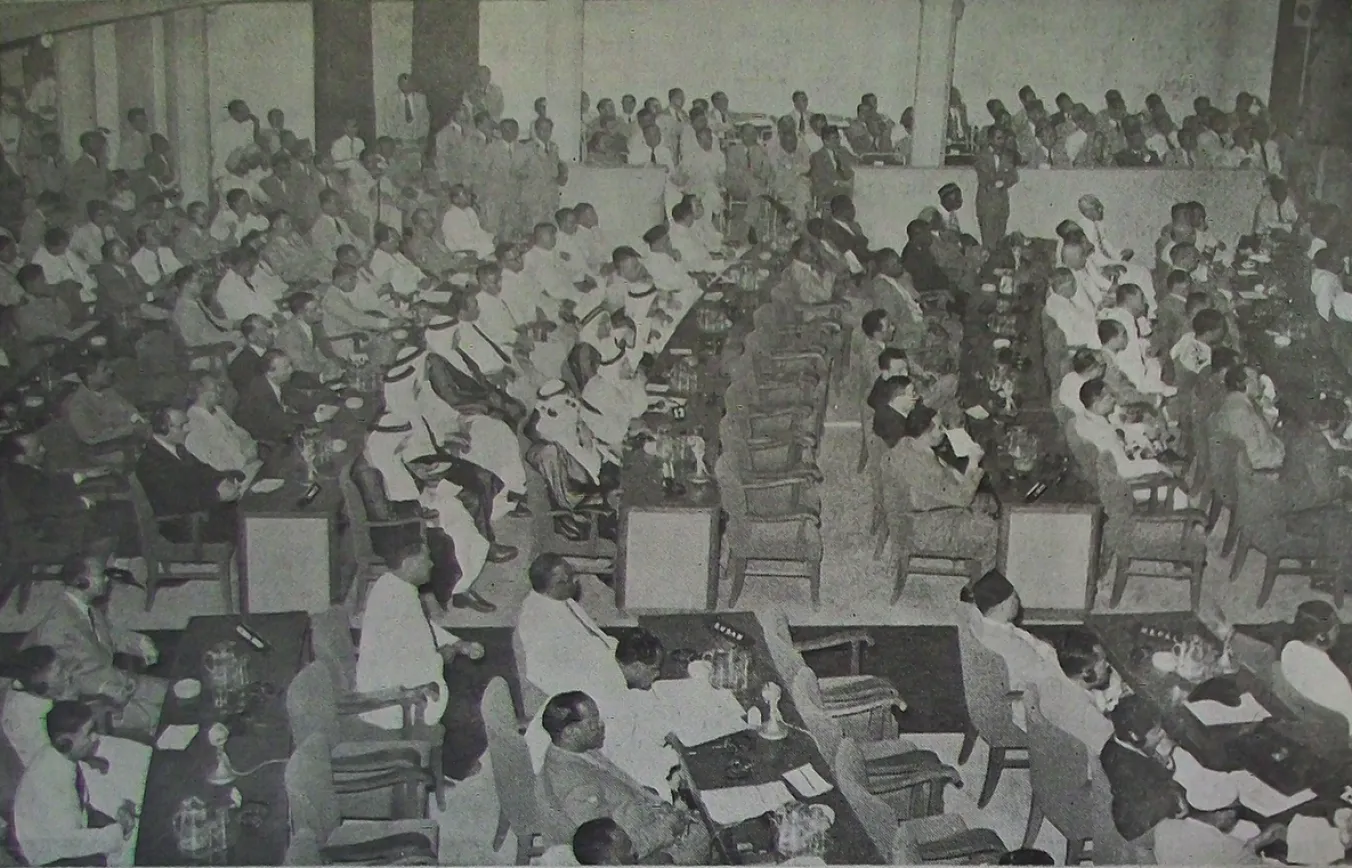

China’s huge growth and trade success have driven the expansion of the Brics alliance — now is a good time for the global South to rediscover 1955’s historic Bandung conference, and learn its lessons, writes ROGER McKENZIE

The revolutions in Mali, Niger and Burkina Faso against the old colonial powers are seldom understood in terms of Africans’ own agency and their rejection of the imperialist humiliation thrust upon them, writes ROGER McKENZIE

From Zimbabwe’s provinces to Mali’s streets, nations are casting off colonial labels in their quest for true independence and dignity in a revival of the pan-African spirit, writes ROGER McKENZIE

Challenging critics of the Sandinista government, the young Nicaraguan union leader FLAVIA OCAMPO speaks to Roger McKenzie about the nation’s progressive health system and how trade unions have been at the centre of social progress

Similar stories