IN NORMAL times, where the main parties of capitalist continuity compete for the mandate to govern Britain they do so compelled by the perceived logic of Britain’s wildly undemocratic electoral system to chase after floating voters in a slice of marginal constituencies where slight shifts in turnout or choice can make a Commons majority or a largely impotent Opposition.

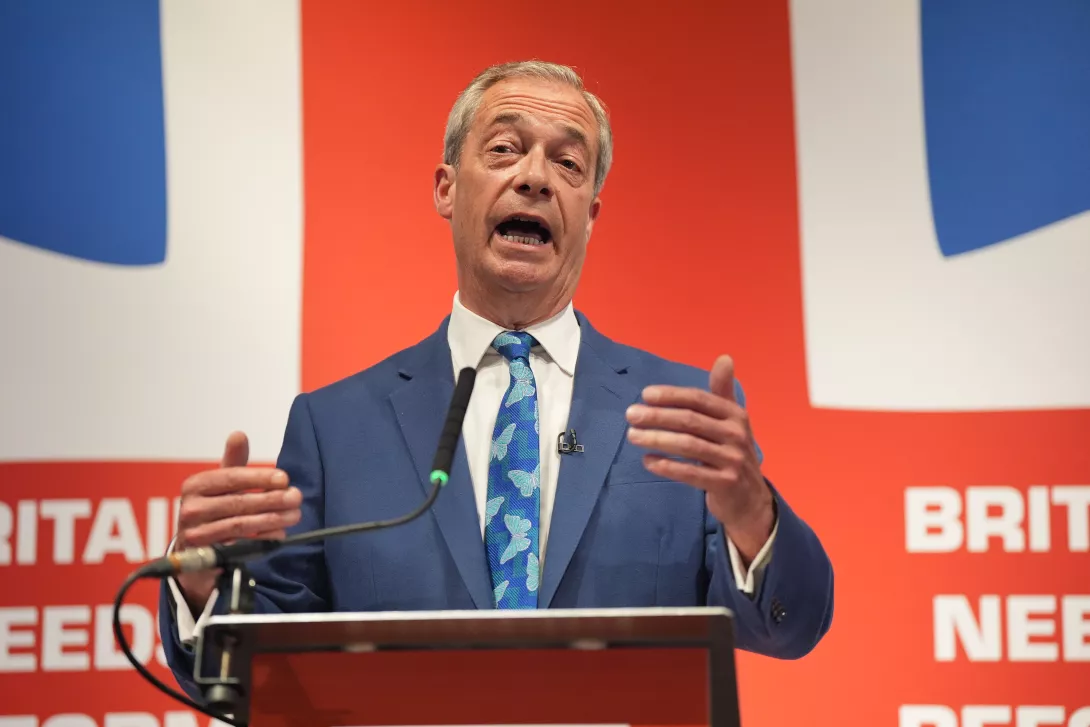

These are not normal times. The latest polling figures have Labour on 41 per cent, down a bit on last month; the Tories on 20 per cent, up a percentage point; the Lib Dems – their former partners in Cameron’s austerity coalition – on 11 per cent and Nigel Farage’s privately owned Reform outfit on 9 per cent, down four points with the Greens up four points on 11 per cent.

Other regional parties make up 8 per cent, up two points.

If Reform maintains its hostility to the Tories at a pitch where to stand down would totally compromise their raison d’etre, the Tories are in deeper trouble than even the polls show.

Farage’s bunch of maverick venture capitalists, racist ranters and finance-sector chancers are unlikely to give the Tories a clear run in risky constituencies unless Labour presents much of a threat to their collective class interests. Given that Starmer has largely convinced the ruling class that nothing vital for capitalist stability is present in Labour’s policy, this seems unlikely.

The UK is not anything like a homogenous entity. Wales and Scotland have a different electoral dynamic to Britain as a whole, the British-ruled slice of Ireland not only another country but another world, while England is a country riven by class, poverty and profound regional differences. This will be a fight constituency by constituency.

Starmer’s managerial appeal explicitly eschews radical claims and is defined by his self-mutilating reprise of Gordon Brown’s explicit 1997 commitment to maintain Tory spending levels.

Thus the reported electoral benefit accruing from Starmer’s wholesale abandonment of Jeremy Corbyn's 2017 election manifesto (the main points of which constituted his leadership pitch to Labour Party members) is a runaway increase of exactly one per cent on Corbyn's 40 per cent of the actual vote. And that in a situation where the Tory vote has eroded to an unprecedented extent.

Recollect that apart from its effect in driving up Labour’s vote by raising working-class participation and energising youth, the radical content of Labour's 2017 manifesto also mobilised a decisive Tory constituency – but one which today is fragmented, demoralised and divided in its loyalties.

The Tory response to their dire polling figures is a barely credible attempt to present Labour under its present leadership as an existential threat to stability, territorial integrity and public order.

This is combined with the opening shots in what looks like becoming a race to the gutter on migration myths and refugee scares shot through with racist appeals to the toxic remnants of imperial nostalgia, British exceptionalism, war hysteria (bring back conscription!) and xenophobia.

How the working class can exert its influence in this election is the political pachyderm in the room.

Labour’s conditional, infinitely negotiable and fragmentary commitment to limited measures of labour law reform is the fetish upon which some trade union leaders fix their hopes and dreams.

Others are absolutely clear that holding Westminster Labour even to this will be a battle.

Ruling-class power in Britain resides not simply in institutions like Parliament, the state, in the ownership of the means of production, distribution and exchange, but in ideas and in the ways we are forced to live. A working class mobilised across a whole range of issues is a force able to change parliamentary arithmetic.

This election campaign is a good place to start.