VIJAY PRASHAD examines why in 2018 Washington started to take an increasingly belligerent stance towards ‘near peer rivals’ – Russa and China – with far-reaching geopolitical effects

Democracy and the Labour landslide

So huge a majority on so small a vote points to the widening gulf between rulers and ruled and a deep crisis of bourgeois democracy, argues BEN CHACKO

TODAY’S march for Palestine will send an uncompromising message to Keir Starmer: there is no honeymoon for a government that backs Israel’s Gaza genocide.

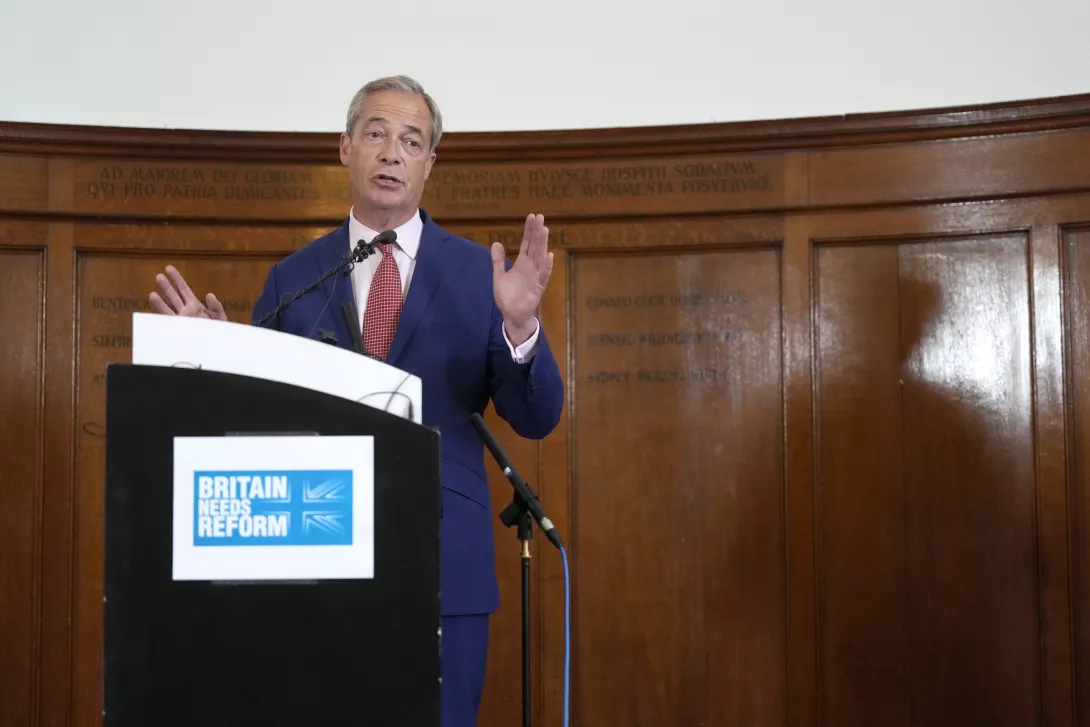

Palestine was an issue at the general election. Four independent MPs have taken seats from Labour standing essentially as single-issue Palestine solidarity candidates: an equal number to the parliamentary breakthrough of the Greens on the soft left and not far behind the five taken by far-right Reform UK.

Many others came close, with Leanne Mohamad falling a few hundred short of ousting the appalling NHS privatisation fan Wes Streeting, perhaps the most frustrating result of the night.

More from this author

Long having been considered the ‘US’s backyard,’ Latin America is the crucible of anti-imperialist struggle – yet with the rise of China as an economic and ideological counterweight to Washington, we see a new phase of that struggle emerge, writes BEN CHACKO

Similar stories

Labour’s low-vote landslide was enabled by the far right and opens the door wider to fascism, argues CLAUDIA WEBBE

by Radhika Desai, Alan Freeman and Carlos Martinez

Communist Party leader ROBERT GRIFFITHS dissects the election results, looking at all of the political spectrum, from the hard right to the far left, and assesses the political landscape it reveals