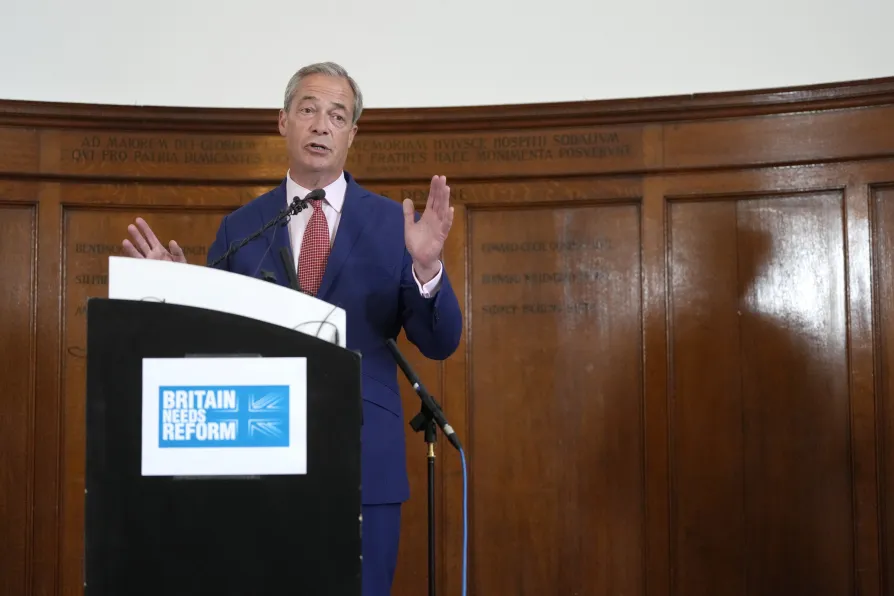

Nigel Farage leader of Britain's Reform Party, speaks during a press conference in Westminster in London, June 14, 2024, while on the General Election campaign trail

Nigel Farage leader of Britain's Reform Party, speaks during a press conference in Westminster in London, June 14, 2024, while on the General Election campaign trail

JUBILATION at the collapse of the Conservatives should be tempered by a look across the Channel. The rise of Reform UK — which even overtakes the Tories in some polls — could forecast a France-style far-right lead in elections in a few years’ time. Nigel Farage certainly hopes it does.

The extent of the Tory rout looks to be historic. Some MPs panic it could be reduced to 60 seats.

Vision narrowed by a long fixation on parliamentary arithmetic, most commentators are unconcerned that the Tory meltdown doesn’t consist of voters flocking to Labour, but to Reform UK. Labour will be the beneficiary anyway, they assume: and they’re probably right. This year.

But the Tory crisis points to something deeper. Why such a catastrophic decline, five years after achieving an 80-seat majority?

Keir Starmer is kidding himself if he thinks this is simply an awakening to Tory sleaze or economic incompetence.

It’s the bitter harvest of decades. Wages have shrunk as a share of national income since the 1970s: something which became painfully clear during the inflationary crisis of 2022-23.

Years of cuts are now causing the breakdown of systems people expect to be there when they need them, from NHS appointments to schools that aren’t falling down, and privatisation has delivered us a water sector in such poor shape that it leaks raw sewage into water courses even on dry days.

These chickens have come home to roost on Rishi Sunak’s watch. But the scale of the earthquake shows we should place the Conservative implosion of 2022-24 alongside the Brexit vote of 2016 and the Corbyn surge of 2015-17: all reflections of revolt against the system, which millions of people now understand works against them, not for them.

Corbynism was mainly a movement of hope. In Brexit hope and anger were mixed. But the Tory haemorrhage to Reform UK is simply a movement of anger. It offers no solutions.

That doesn’t mean it cannot triumph. In France similar grievances have already eclipsed the old parties of left and right.

Emmanuel Macron sought to reboot centrist liberalism with a shiny new electoral vehicle and a raft of concessions to the Islamophobic right. His success was always exaggerated. The “anti-system” vote remained much larger than Macron’s in 2017 and 2022, but he remained ahead of either the far right or socialist left individually.

That is no longer the case. A poll cited by the Financial Times for the snap parliamentary election under way shows Marine Le Pen’s bloc in the lead in 362 seats: against her, the Popular Front of socialists and communists leading in 211, since they rightly refused Macron’s ploy to line them up behind him; and Macron’s allies leading only in three.

The French left understands that alignment with the liberals is the road to oblivion. It is to side with the very status quo that ordinary people are rejecting, and allows the far right to pose as champions of the discontented majority.

Labour should watch out. Its economic orthodoxy means the system failure people now blame on the Tories will be blamed on it soon enough. Even now, there is little enthusiasm for a Starmer government: a YouGov poll last week put Labour support on 37 per cent, lower than Corbyn’s 2017 vote and only on course for a landslide because of the Tory collapse.

The Tories have gone from political dominance — something they achieved by posing as the party of rupture with the system in the form of Brexit — to near-pariah status in five years. Starmer’s team, showing no understanding that Britain’s economic model can no longer reward anyone but the super-rich, looks capable of repeating the feat.

And unless the left is able to build a coherent system-challenging movement in the meantime, Farage may then be where Le Pen is now — on the cusp of power.

Every Starmer boast about removing asylum-seekers probably wins Reform another seat while Labour loses more voters to Lib Dems, Greens and nationalists than to the far right — the disaster facing Labour is the leadership’s fault, writes DIANE ABBOTT MP

Reform’s rise speaks to a deep crisis in Establishment parties – but relies on appealing to social and economic grievances the left should make its own, argues NICK WRIGHT