VIJAY PRASHAD examines why in 2018 Washington started to take an increasingly belligerent stance towards ‘near peer rivals’ – Russa and China – with far-reaching geopolitical effects

Another dimension to the Tolpuddle story: colonialism

KEITH FLETT uncovers the links between Dorset landowners, Caribbean plantations, slavery and the prosecution of trade unionists, revealing a darker side to the Tolpuddle Martyrs’ story

WILLIAM CUFFAY, the black leader of London Chartism in 1848, is a well-known figure in British history thanks in part to the pioneering work done by the later Peter Fryer with his book Staying Power.

There is now a good deal more research and published history about black people in Britain going back at least to Tudor times. Yet it remains the case that little is known about a black presence in the Chartist movement.

The presence of black workers who had come to Britain on navy or merchant ships, servants and others, meant there was a considerable black population in Victorian Britain.

More from this author

KEITH FLETT looks back 50 years to when the Iron Lady was elected Tory leader…

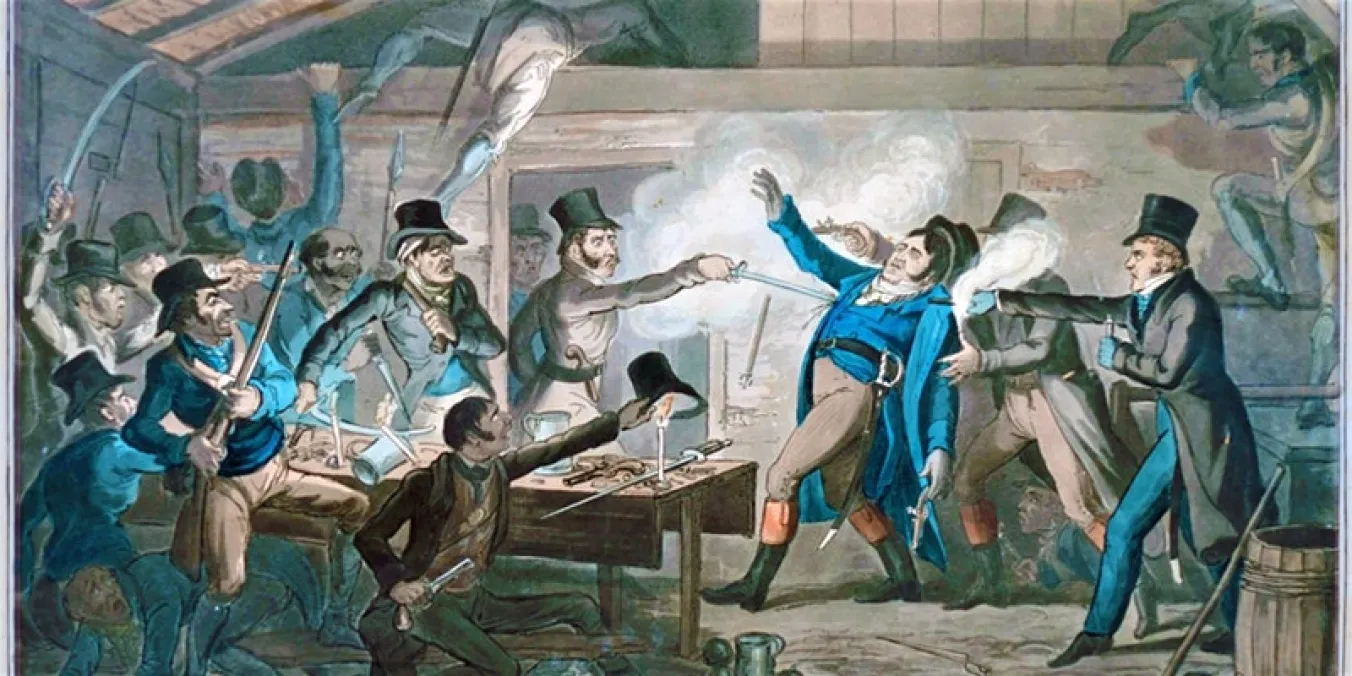

The legacy of an 1820 conspiracy in revenge for Peterloo resonates down the ages, argues KEITH FLETT

Britain’s first woman Chancellor delivers the same old fudge, as Labour’s commitment to economic orthodoxy, seen throughout its history, always betrays working people, writes KEITH FLETT

Every few years, it seems like the ‘right time’ to build a new left party — but what are the right conditions, asks socialist historian KEITH FLETT, looking back at the last two centuries and the insights of Ralph Miliband and EP Thompson

Similar stories

Union leaders demand Labour deliver ‘deep and ambitious change’ as thousands attend the Tolpuddle Martyrs Festival in Dorset

Unison South West regional secretary KERRY BAIGENT charts the recent successes for industrial action and organising in her area, and outlines the challenges ahead, urging Labour to deliver on workers’ rights and social care

With a Labour government now in power it’s time to rebuild in the interests of working people, says MICK LYNCH

After 14 years of Tory rule, Labour are finally in power, with some welcome measures announced in this week’s King’s Speech — but, as ever, the Devil will be in the detail, warns STEVE PREDDY