LABOUR is moving on pay. But in a framework which pits pay rises against other much-needed investment in public services and seeks to divide unions, which exist to fight for workers at work, from those campaigning to reverse Tory attacks on social security.

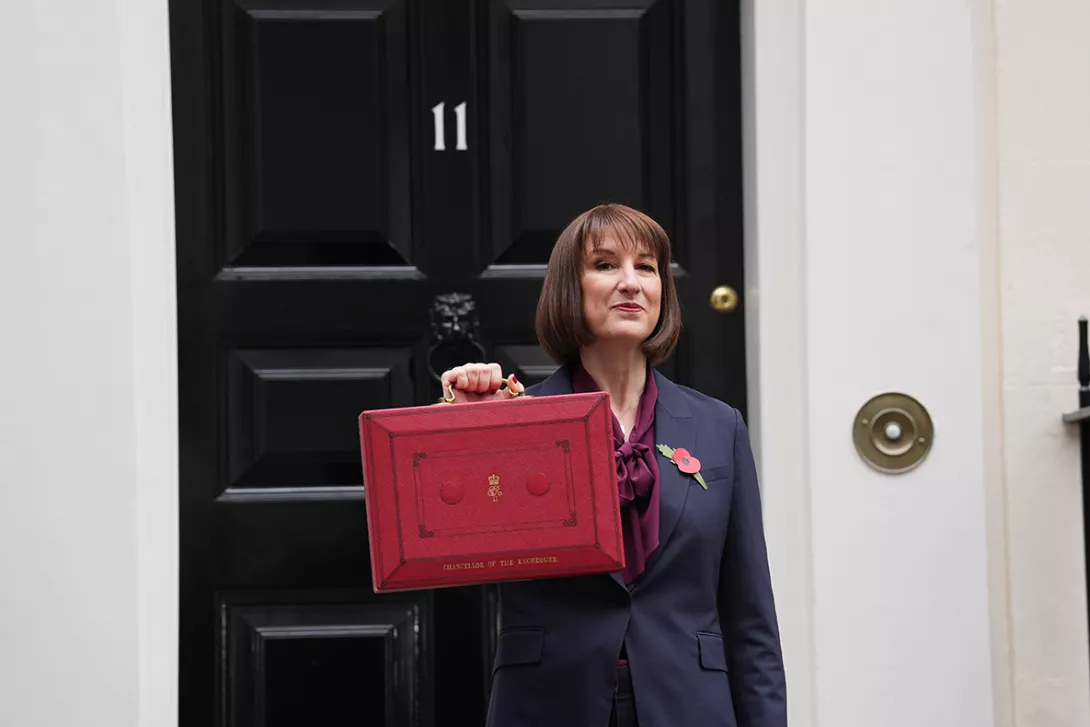

This does not mean the pay rises announced by Rachel Reeves on Monday, or today’s movement on the minimum wage — changing the Low Pay Commission’s remit to take the cost of living into account when setting it, committing to abolish age bands for adults and targeting alignment with the higher National Living Wage — are not most welcome.

About £9 billion of the £22bn budget overspend Reeves says the Tories hid stems from Labour agreeing pay review bodies’ recommendations to award teachers and NHS staff 5.5 per cent raises, well over double the 2 per cent planned by the Conservatives.

As National Education Union leader Daniel Kebede observed, this is only a step in the right direction: it does not restore the value of pay lost since the bankers’ crash; and it is the result of sustained industrial action, something Reeves admits, since she cited the costs of continuing strikes when asked to justify the awards. But it is still a step, and may avert significant industrial action across public services this year.

Recruitment and retention difficulties are a key driver of the crisis across public services and raising pay is the single most effective way to address them (since overwork and burnout, which also drive people out of careers in teaching or the NHS, are themselves linked to understaffing).

But they are not the only crisis. Scrapping plans to repair, renovate and build new hospitals in a bid to “balance the books” — by which Reeves means hit arbitrary targets for eliminating the budget deficit by a particular date — echo former Tory minister Michael Gove’s disastrous decision to abolish the Building Schools for the Future programme in 2010, which directly led to last year’s crumbling schools emergency.

Avoiding necessary infrastructure investment is a false economy. This is particularly true when a whole society needs adapting to changing conditions, in our case primarily climate change (an ageing society is, thanks to immigration, less of a challenge in Britain than in some other rich countries).

The axe falling on rail upgrades and reopening old routes is bad enough, but the logic must be defeated before the Chancellor is able to unleash her promised “difficult choices” in the autumn, given the enfeebled state of everything from local government to flood defences.

Nor is Britain’s health crisis forged in a health sector bubble. The Tories saw rising sickness absence as evidence of a work-shy culture, proposing “solutions” like stopping GPs from writing sick notes. The reality is that Britain has become physically and mentally sicker: a development inextricably linked to rising poverty.

Cutting winter fuel payments to millions of households is ominous: it will lead to more winter deaths. It also imitates Tory divide-and-rule tactics, pitting pay rises for those in work against social security payments for those who are not.

And Labour is setting in stone inflexible fiscal targets by boosting the powers of “independent” overseers like the Office for Budget Responsibility.

In reality no more independent than the corporate voices on pay review bodies, this simply empowers conformist economists trained in neoliberal dogma, whose disastrous record at the Bank of England has included interest rate rises that impoverish ordinary people and deliver super-profits for the banks. It is an anti-democratic move trying to disguise economic choices as laws of nature.

If industrial action forced the changed tune on public-sector pay, a means must be found to force ministers to raise overall spending too. We need a united campaign for an alternative economic strategy, working with and through organisations like the People’s Assembly to build power in the community.