CHRISTOPHE DOMEC speaks to CHRIS SMALLS, who helped set up the Amazon Labor Union, on how weak leadership debilitates union activism and dilutes their purpose

Kenny MacAskill remembers a ‘Sovietologist’ and voice for peace and reconciliation at the Carnegie Council for Ethics in International Affairs

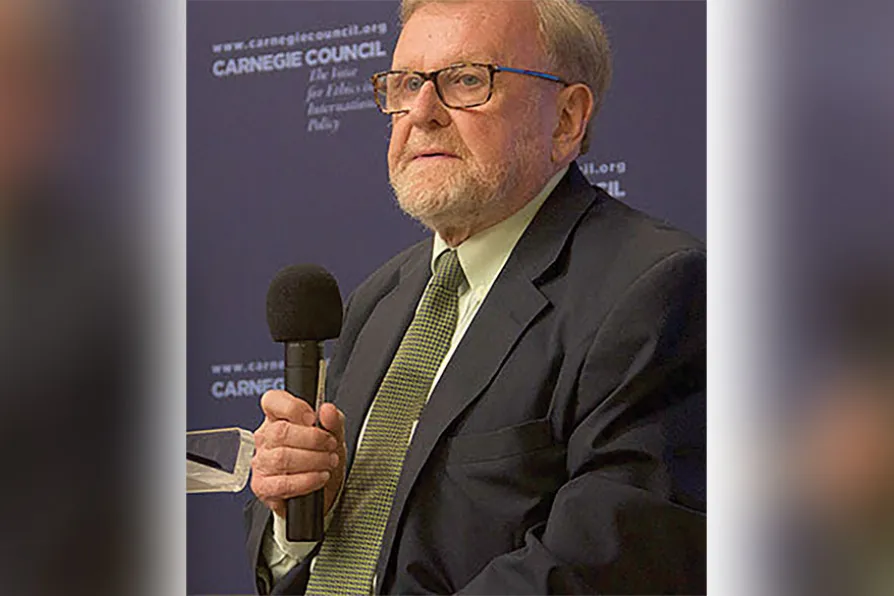

David Speedie

David Speedie

ANDREW CARNEGIE was one of America’s “robber barons,” but also stated that “true success is measured not by how much we accumulate, but by how much we give back.”

His philanthropy’s well known around the world. Libraries, halls and even public parks in his native Dunfermline testify to that. What’s less well known is his opposition to war and the legacy he left to promote global peace and understanding.

The Carnegie Council of New York stands at the centre of that work, and at the heart of that organisation for decades was another emigrant Scot, David Speedie — chairing the Programme on International Peace and Security from 1992-2007, then senior fellow on US global engagement at the sister organisation, the Carnegie Council for Ethics in International Affairs from 2007-17.

His tenure there covering the fallout from the collapse of the Soviet Union saw him involved at the highest levels in international affairs and domestic US politics, making him well-known and even on first-name terms with many international leaders and senior politicians across the globe

Born in Stirling in 1946, David Speedie, grew up in nearby Bridge of Allan and was the archetypal Scottish lad o’pairts. His grandfather was a sergeant major in the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders but when he died, his father, also David, was required to give up a legal apprenticeship and take employment as an electrician.

Marrying Catherine from the Hamilton area, life wasn’t easy for the family, with business failures and numerous house flits. But despite that, David and his two brothers would be high achievers. He was the first in the family to go to university when he went to St Andrews, studying English language and literature, needless to say gaining a first-class honours degree.

A postgraduate degree and some lecturing at St Andrews were followed by a Kennedy Scholarship to Harvard. There from a selection panel chaired by the philosopher Sir Isaiah Berlin, studying alongside the likes of Mervyn King, the future Bank of England governor. While on that sojourn he met an American girl Eveline, whom he would marry and who would become his lifelong partner until her death in 2016.

A brief return to Scotland saw him lecturing at Telford College during the day and at night at Saughton Prison. Evidence if ever there was that David had no airs or graces and could mix easily in any company, the rank for him, as Rabbie Burns would say, “was but the guinea’s stamp.”

He returned to the US, working for the British embassy in Washington DC before moving to Philadelphia to become the city’s director of cultural affairs.

However, moving to the Carnegie Council it was there that he found his forte, striving for global peace and understanding. Working his way up from being a programme officer in the Co-operative Security Programme to being the programme chair. These were both interesting and dangerous times, stretching from the dark days of the cold war to the fractious world following the Soviet Union’s collapse — arms control as weapons of mass destruction threatened humanity, followed by regulating and monitoring nuclear and chemical stockpiles, all as new fields of conflict evolved.

David humorously recalled meetings in The Hague on Chechnya. Noting that he was Scottish, the Chechen delegation, dressed in full battle regalia, told him that their leader Maskhadov, was a huge fan of “Braveheart” which had just been released, seeing it 10 times. David sagely advised that it wasn’t the example to follow. His work saw him visiting Russia often and bearing witness to many of the problems the world faces today.

As the Soviet Union collapsed, he was there to support peace and understanding. Others, such as the Heritage Foundation though, had malign intent. A DVD sent by him disclosed a supposed briefing on democracy provided by that group to Russians who would now be described as the oligarchs. Two aspects were starkly exposed — firstly how they pushed that a lower turnout could work well by offering increased leverage and that scapegoating minorities also had a major role. Hardly a rallying call for public participation in a fledgling democracy and the outcome shown in recent elections and social ills in Russia.

Having been present when assurances were given to Russia by Western leaders that there would be no Nato expansion, he had forewarned of the risks being taken in Georgia and Ukraine — attacks in past centuries whether by Mongols, Napoleon or Hitler being burned deep in the Russian psyche. While condemning the Russian invasion of Ukraine, David was always counselling for peace and the avoidance of any escalation.

As the world’s focus changed, David moved from being as he described it a “Sovietologist” to becoming project director on Islam and special adviser to the president of the council. Upon his retirement, he remained involved in peace and politics, writing, lecturing and sitting on the board of the American Committee for US-Russia Accord, which sought to lessen tensions between the two great powers, also assisting the efforts of Rust Belt Rising, a Democrat organisation which sought to get the party and movement back and reconnected with its grassroots.

Though settled in the US David never forgot his native land, retaining both his accent and an affection for football throughout his life. His uncle, Finlay Speedie, had played for Rangers, but he was friendly with George O’Neil, a former Celtic player who had also moved across the Atlantic.

David had been the Labour agent when Sir Alex Douglas-Home was parachuted into West Perthshire and Kinross to become prime minister. In his later years though he became a great supporter of Scottish independence, facilitating Alex Salmond’s talk at the Carnegie Council and being wise counsel to the wider movement.

Passing away in Virginia on October 2, he’s survived by his son David, granddaughter llsa, and brothers Alan and Denis. As the US-Russia Accord website recorded, “Those who knew David will remember him not only as a brilliant man but as a decent and empathetic one.”

Building is the solution for much of our housing crisis – and will also help to address poverty, ill health, and even anti-social behaviour and alienation, writes KENNY MacASKILL

KEN COCKBURN assesses the art of Ian Hamilton Finlay for the experience of warfare it incited and represents