JOHN GREEN, MARIA DUARTE and ANGUS REID review Fukushima: A Nuclear Nightmare, Man on the Run, If I Had Legs I’d Kick You, and Cold Storage

MARJORIE MAYO recommends a compelling account of how women survived a Nazi concentration camp and lend their experience to today’s fight against the far right

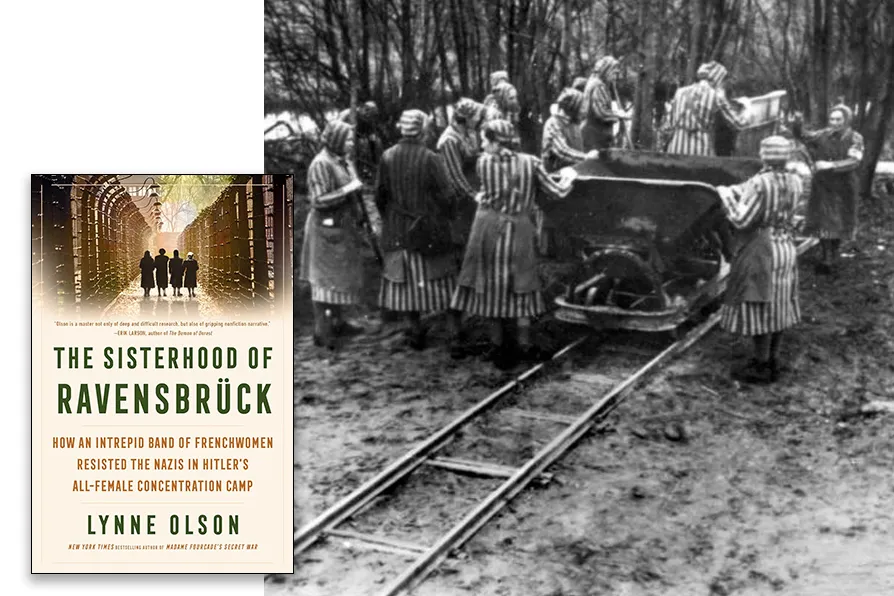

Women prisoners in Ravensbruck concentration camp, working under extreme duress, 1939. [Pic: German Federal Archives/CC]

Women prisoners in Ravensbruck concentration camp, working under extreme duress, 1939. [Pic: German Federal Archives/CC]

The Sisterhood of Ravensbruck

Lynne Olson, Scribe, £22

THE subtitle of this compelling book summarises the story that follows: “How an intrepid band of Frenchwomen resisted the Nazis in Hitler’s all-female concentration camp.”

Although far from being the first publication to celebrate the extraordinary courage and resilience of these remarkable women, The Sisterhood Of Ravensbruck has particular relevance in the current context. The survivors themselves were only too aware of the continuing need for sisterhood and solidarity in face of the challenges from the far right, in more recent times.

The women came from a variety of backgrounds, including traditionally conservative, Catholic backgrounds. One of them, Genevieve de Gaulle, was the niece of Charles de Gaulle (whom she strongly supported). But they shared a passionate commitment to resisting Nazism.

The book starts with the back stories of several of the most prominent women, including teenager Anise Girard, who was only 18 when she became involved in the Resistance. Resistance groups were very amateur initially, Olson goes on to explain, and very vulnerable to being infiltrated, although the communists were more organised. Olson refers to the efforts of Resistance hero, Jean Moulin, to bring the different groups together.

Once captured and imprisoned in Ravensbruck concentration camp — described as “Dante’s seventh circle of hell.” This was initially a work camp rather than an extermination camp but it was still organised with extraordinary brutality and gratuitous violence. The situation deteriorated even further subsequently, towards the end of the war, when the Nazis installed a gas chamber to exterminate those who could bear witness to their crimes.

An estimated 130,000 women from Nazi-occupied Europe were sent to this camp, but as many as 40,000 died there, of starvation, disease, torture, shootings, lethal injections and medical experiments.

Faced with these horrors, the French women developed extraordinary bonds of solidarity, bonds which were essential to their survival. They helped each other out in very practical ways, covering for those who became sick, sharing food and fuel, for example — and never betraying one another despite the threats and punishments that they faced from the Nazi guards.

Most importantly, they provided each other with moral support, keeping alive a shared commitment to resistance. “We helped each other — and joked a lot,” one of them reflected. And “To laugh is to resist”; a view that some of the other prisoners found completely bizarre.

The French women’s composition of a series of operetta sketches was beyond the Polish women’s comprehension. The operetta was never actually performed in Ravensbruck, but a version was eventually performed in 2007 and subsequently.

While the French women spoke of their intense bonds with each other, their sense of sisterhood and solidarity extended to other groups as well. Anise Girard was particularly instrumental in enabling a group of Polish women to survive, despite having been the victims of horrific Nazi medical experiments. After the war, she was determined to keep her promise to these women, working with others to enable them to gain compensation and treatments for their injuries and associated medical conditions.

The Resisters were also determined to tell their stories, to document the atrocities that had been perpetrated against them and against other victims including the Poles. Between them they subsequently produced a book to bear witness, although French publishers were not initially interested, preferring not to dwell on such a traumatic past period. A film was eventually made and shown, as well.

One of the key figures in these processes of documentation was an anthropologist, Germaine Tillion. She was already well experienced, with professional interview and recording skills, having worked in Algeria before the war. Becoming a famous public intellectual, after the war, she revisited Algeria, expressing her horror at the use of torture by French troops during the war of independence. The French were behaving like Nazis, in her view.

More recently, those of the resisters who were still alive also voiced their concerns about the rise of the far right, being only too well aware of where this could lead.

“Yes we have worries,” they explained, although they continued to have hope. Such appalling crimes had been committed. But the resisters had also experienced acts of such generosity and kindness that the bonds of solidarity remained strong among those who survived, as they supported each other through their varying experiences, and the ups and downs of readjusting to life after Ravensbruck.

Their stories provide an important corrective to earlier accounts of the Resistance, accounts which tended to focus on the achievements of male heroes. There was little, if any, recognition of the contributions of these courageous women. This has been a continuing struggle. It was only in 2015 that two of them, Germaine Tiller and Genevieve de Gaulle, were publicly honored at the Pantheon, only the second and third women to be honored in this way.

Morning Star readers will find The Sisterhood of Ravensbruck disturbing yet compelling. Whatever their backgrounds and political affinities, these courageous women were able to build and maintain solidarity and commitment to humane values, commitments that they succeeded in maintaining in subsequent years.

I feel that there are contemporary implications here, in the context of the growth of the far right.