GORDON PARSONS applauds a marvellous story of human ingenuity and youthful determination, well served by a large and talented company

ALEX HALL is unsurprised by the evidence of systemic corruption in the US, and unsettled by the undertone of alarm

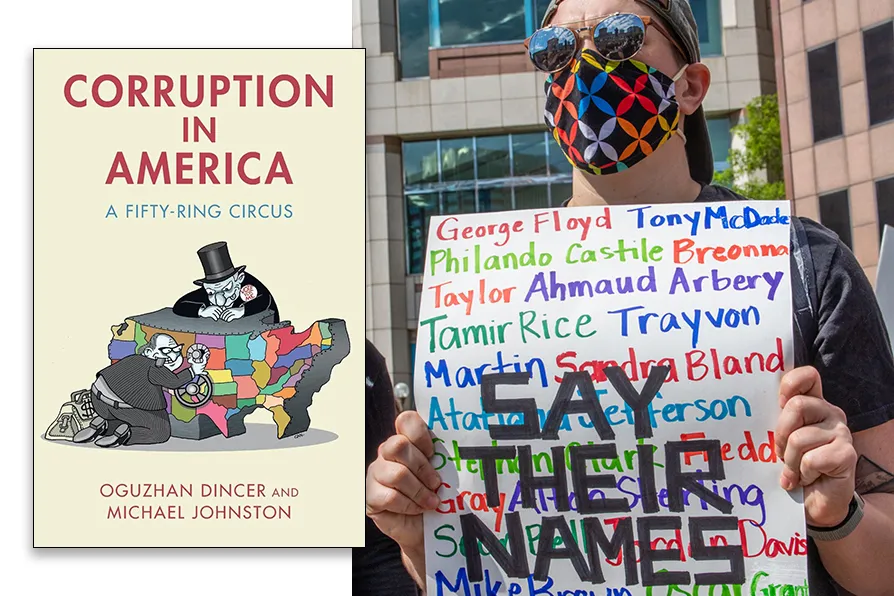

EVIDENCE SPEAKS: At a protest over the killing of George Floyd, a sign lists a few of the many unarmed African Americans killed by law enforcement officers in the US, May 30 2020. [Pic: Becker1999 from Grove City, OH/CC]

EVIDENCE SPEAKS: At a protest over the killing of George Floyd, a sign lists a few of the many unarmed African Americans killed by law enforcement officers in the US, May 30 2020. [Pic: Becker1999 from Grove City, OH/CC]

Corruption in America: A Fifty Ring Circus

Oguzan Dincer and Michael Johnston, Cambridge University Press, £26.99

THERE’s an unsettling undertone in this academic treatise by two professors of economics and politics, respectively. While the ostensible subject under examination is evident by its title, the conclusions do not paint a picture of a society that merely needs a few technical tweaks to reset course. That was not the point of the book, in any case, so it’s notable that some of the conclusions are far reaching.

The authors set out to examine empirically corruption in the individual states that make up the US. To this end they corral an impressive array of statistical indexes and quantifiable evidence to produce rankings, indications of cause and effects, and also apply economic indicators and theories. The work also draws on a wide review of published literature.

This analysis is then focused onto real-world phenomena as it seeks to elucidate key relationships between corruption and the real lives of Americans. This includes relationships between corruption and economic and political outcomes, the killing of black Americans by the police, environmental policy and its implementation, and public health with a focus on the Covid-19 pandemic.

Firstly, what is corruption? In itself this isn’t a single measurable thing, and throughout the book the authors distinguish between legal and illegal corruption. Legal corruption includes the revolving door between politics and lobbying, for example, and the fact that in the US political funding is protected as free speech under the first amendment. Illegal corruption is that which is legislated against, such as paying bribes to government officials for contracts, and is detailed in prosecutions.

Either way, corruption itself is a slippery thing to define, but throughout the work the authors are clear that it involves unequal access to power and decisions taken which exclude and abuse the people it affects unfairly. This is complicated by the size and scale of the US government. While there are more than 93,000 “units of government” in the US, California would be the world’s fifth-biggest economy and Texas the fourth-biggest oil producer.

Corruption effects the economy, and in particular economic inequality. It favours the haves rather than the have-nots. It affects public services in reducing their quantity and quality, increases tax burdens on those who don’t have the resources to avoid it and skews redistribution programmes. Trust itself, in government and each other, declines. A 2015 poll showed that nearly 80 per cent of respondents agreed that “when it comes to politics, people like me get overruled by the big campaign contributors”. In the US, big campaign contributions are protected speech.

The police maintain a social order, and as such, also hierarchies of power. They have powerful unions which are political players in themselves. Corruption weakens environmental safeguards and makes big challenges ineffective. In matters of public health, corruption is embedded in and perpetuated by the workings of institutions, and by economic and political inequality. In short, it intertwines with many other facets of US society.

The authors repeatedly draw links and inferences from across the spectrum of US malaises. Despite some key historical strengths, the US is not a well society. Dealing with corruption isn’t something they can prescribe with a 10-point plan, or just by voting the right way.

They say: “At the moment it seems hard to envision any process of democratic renewal taking place at the ballot box without the intervention of some system-shaking crisis. That we may be in the opening stages of such a crisis casts some of the implications of this book in a particularly discouraging light.“

The empire is rotting from within.

Looking for moral co-ordinates after a tough year for rational political thinking and shared human morality

ALEX HALL is frustrated by a book that ducks a clear definition of terrorism and fails to perceive the role of the state in sponsoring it