Labour prospects in May elections may be irrevocably damaged by Birmingham Council’s costly refusal to settle the year-long dispute, warns STEVE WRIGHT

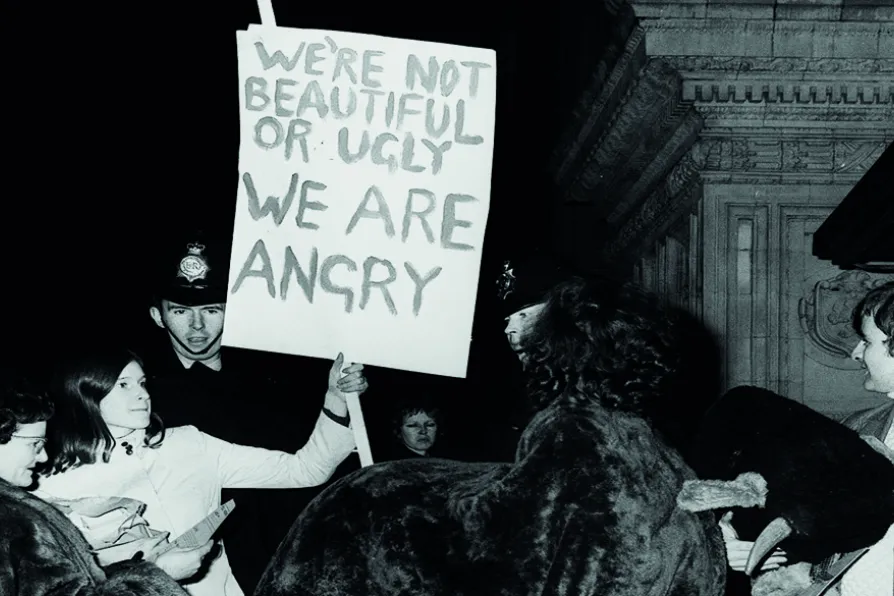

Miss World is the oldest 'beauty pageant.' November 1970 it was disrupted by women's liberation protesters (pictured) who stormed the event armed with flour missiles, water pistols filled with ink, rotten fruit and stink bombs. The event however, still takes place today.

Miss World is the oldest 'beauty pageant.' November 1970 it was disrupted by women's liberation protesters (pictured) who stormed the event armed with flour missiles, water pistols filled with ink, rotten fruit and stink bombs. The event however, still takes place today.

THE film Misbehaviour is currently on general release. It is about the protest at the 1970 Miss World beauty contest, compered by reactionary “comic” Bob Hope, where feminists disrupted proceedings at the Albert Hall by throwing flour bombs and rotten vegetables.

In the film Keira Knightley plays one of the protesters, Sally Alexander. The film also features a scene, manufactured for dramatic effect, with her then partner Gareth Stedman Jones.

Both are socialist historians and founding editors of the History Workshop Journal, which continues to be published to this day, styled as a journal of socialist and feminist historians.

Research shows Farage mainly gets rebel voters from the Tory base and Labour loses voters to the Greens and Lib Dems — but this doesn’t mean the danger from the right isn’t real, explains historian KEITH FLETT