The selection, analysis and interpretation of historical ‘facts’ always takes place within a paradigm, a model of how the world works. That’s why history is always a battleground, declares the Marx Memorial Library

WINSTON CHURCHILL was no friend of the working class, but we should follow his advice of never letting a good crisis go to waste, and not repeat the mistakes of 2008, when we did exactly that.

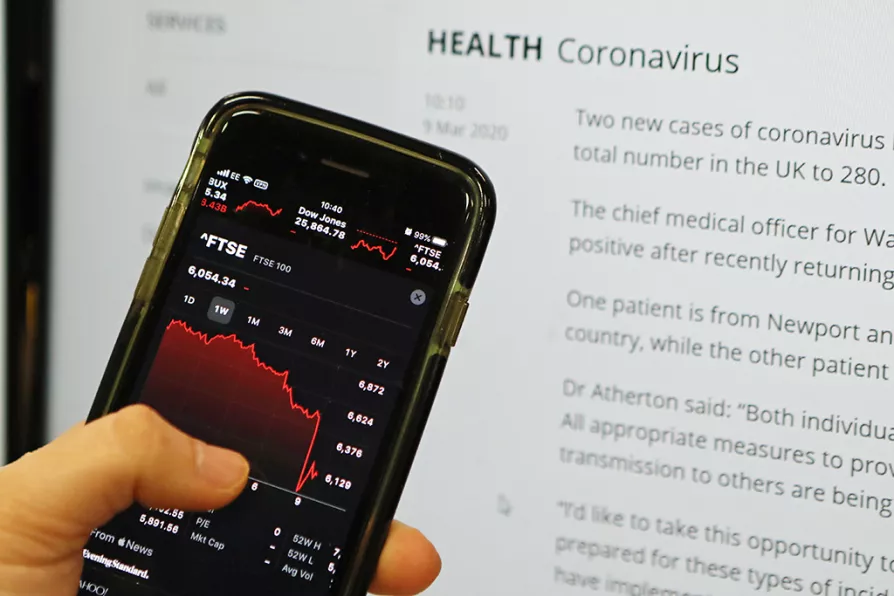

Back then, the subprime mortgage scandal threatened to bring down the entire capitalist infrastructure, prompting the US Federal Reserve to invest an estimated $16 trillion in bailouts to banks and corporations around the world.

Rampant speculation on obscure and risky financial instruments unleashed by globalised financial capital seeking investment opportunities, unrestrained by national constraints, had brought the international banking system close to collapse.

From summit to summit, imperialist companies and governments cut, delay or water down their commitments, warn the Communist Parties of Britain, France, Portugal and Spain and the Workers Party of Belgium in a joint statement on Cop30

In 2024, 19 households grew richer by $1 trillion while 66 million households shared 3 per cent of wealth in the US, validating Marx’s prediction that capitalism ‘establishes an accumulation of misery corresponding with accumulation of capital,’ writes ZOLTAN ZIGEDY

With turnout plummeting and faith in Parliament collapsing, BERT SCHOUWENBURG explains how radical local government reform — including devolved taxation and removal of party politics from town halls — could restore power to communities currently ignored by profit-obsessed MPs

The US president’s universal tariffs mirror the disastrous Smoot-Hawley Act that triggered retaliatory measures, collapsed international trade, fuelled political extremism — and led to world war, warns Dr DYLAN MURPHY