Labour prospects in May elections may be irrevocably damaged by Birmingham Council’s costly refusal to settle the year-long dispute, warns STEVE WRIGHT

WITH the government’s chaotic handling of Covid-19 lockdown restrictions, suddenly announcing changes late at night on Twitter, the attractiveness of a summer break in Britain, for those still able to afford it, has more attraction than usual.

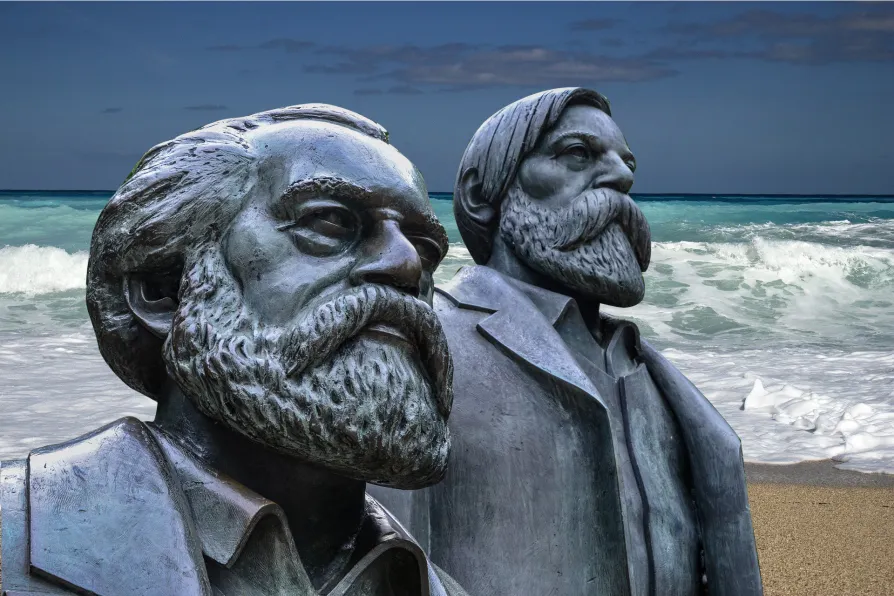

The August weather is notoriously unreliable, but for socialists there is a chance to visit some of the locations that Marx and Engels enjoyed in the second half of the 19th century.

Not quite all are by the sea. There are references in the correspondence to Buxton, then a major spa town, and within reach of Manchester, for example.

The summer saw the co-founders of modern communism travelling from Ramsgate to Neuenahr to Scotland in search of good weather, good health and good newspapers in the reading rooms, writes KEITH FLETT