The Bard stands with the Reformers of Peterloo, and their shared genius in teaching history with music and song

Comma Press Bertolt Brecht

[Roger and Renate Rossing/Creative Commons]

Comma Press Bertolt Brecht

[Roger and Renate Rossing/Creative Commons]

PLAYWRIGHT and poet Bertolt Brecht (1898-1956) is one of the most significant Marxist literary figures of the last century and it seems appropriate that a new translation of his collected poems has just been published at a time when the centenary of the political assassination of Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht is being marked.

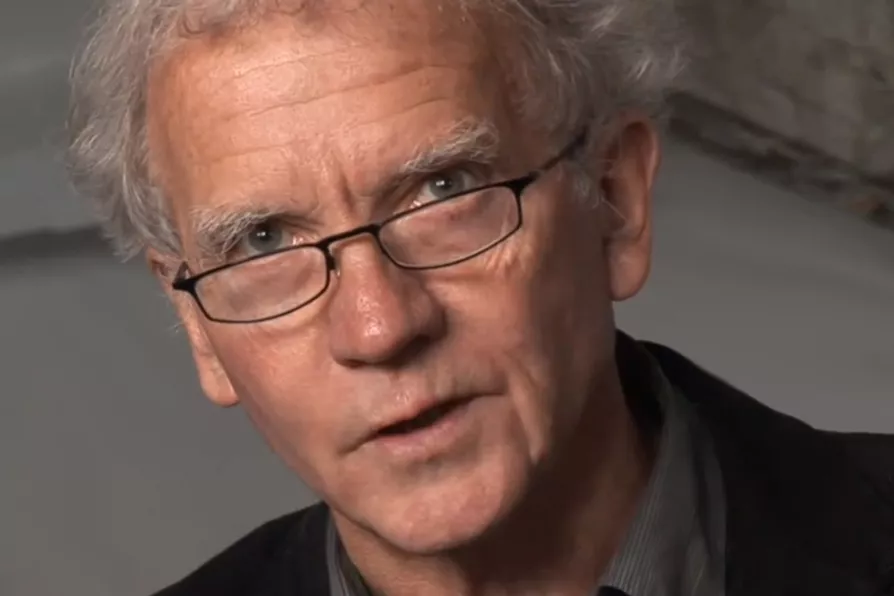

This massive joint undertaking by David Constantine and Tom Kuhn is a highly welcome contribution to Brecht’s study and enjoyment in English. Salford-born Constantine, a highly regarded poet in his own right, is an award-winning translator and short-story writer and here he answers questions about this major task and the pleasures and pains of translating poetry.

RUTH AYLETT reviews two collections of outright political poetry

FIONA O'CONNOR recommends a biography that is a beautiful achievement and could stand as a manifesto for the power of subtlety in art