Labour prospects in May elections may be irrevocably damaged by Birmingham Council’s costly refusal to settle the year-long dispute, warns STEVE WRIGHT

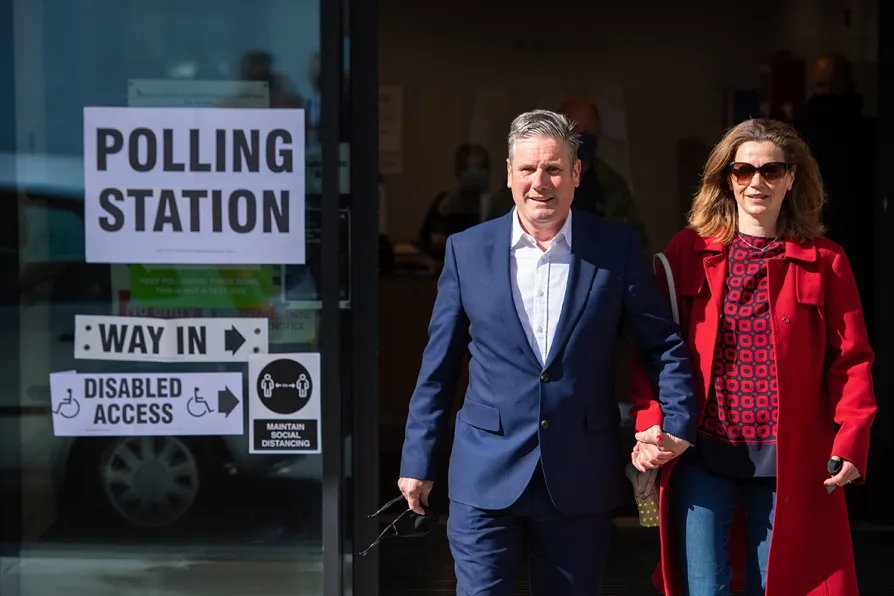

Labour leader Sir Keir Starmer and his wife Victoria leave after casting their votes at Greenwood Centre polling station, north London, on May 2021

Labour leader Sir Keir Starmer and his wife Victoria leave after casting their votes at Greenwood Centre polling station, north London, on May 2021

THE Tory culture war, which sees incessant media talk about a Red Wall of north of England parliamentary seats that have been Labour since the 1950s or ’60s, has a complex and interesting history.

The original motor was George Osborne’s Northern Powerhouse which did little or nothing to address issues of deprivation and poor public services. More recently a focus was on Brexit, where it was argued, with a degree of justification, that some Labour voters would not vote for a party that backed Remain.

Jeremy Corbyn did a good deal to address this point successfully in 2017 but then came arch-remainer and former director of public prosecutions Sir Keir Starmer.

Who you ask and how you ask matter, as does why you are asking — the history of opinion polls shows they are as much about creating opinions as they are about recording them, writes socialist historian KEITH FLETT

The historic heartland of anti-fascist resistance and mining militancy now faces a new battle — stopping Nigel Farage. ANDREW MURRAY meets ex-Labour MP Beth Winter and former Plaid leader Leanne Wood, the two socialists leading the resistance

Research shows Farage mainly gets rebel voters from the Tory base and Labour loses voters to the Greens and Lib Dems — but this doesn’t mean the danger from the right isn’t real, explains historian KEITH FLETT