Channel 4’s Dirty Business shows why private companies cannot be trusted with vital services like water, says PAUL DONOVAN

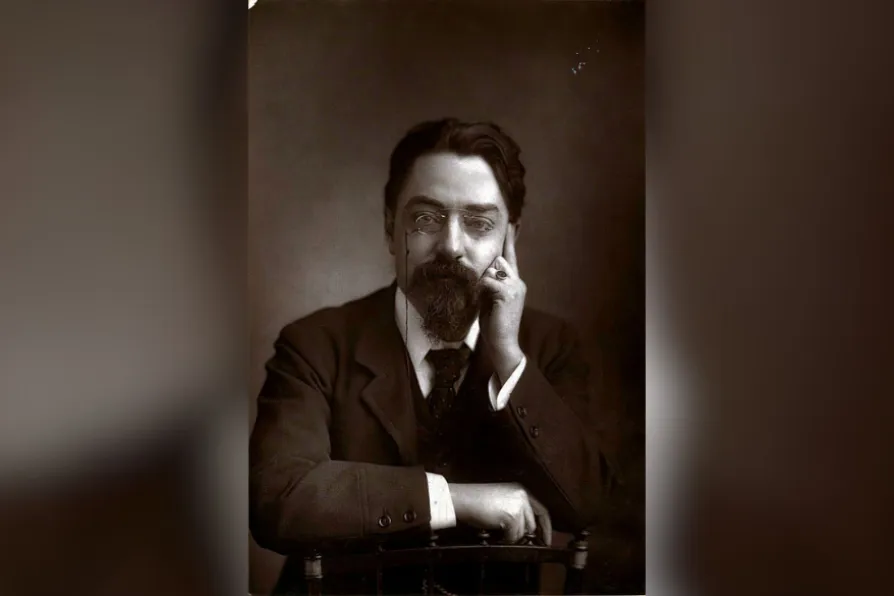

LABOUR GRANDEE: Sidney Webb

LABOUR GRANDEE: Sidney Webb

THE Labour Party’s history is not something much discussed at Labour conferences. There are occasional nods to Clement Attlee and Harold Wilson and of course Tony Blair.

The Labour Party constitution, written by Sidney Webb in 1918 and amended since, is usually only discussed when the leadership is trying to work out how to gather more power for itself and less for the unions and ordinary members.

A recent exception was the period from 2010 to 2019 under the leadership of Ed Miliband and then Jeremy Corbyn, when more power was given to members and membership numbers boomed. The current leadership of Sir Keir Starmer owes a good deal to the fact that the Labour right was concerned that the left might gain control of the order of service in Labour’s broad church, as Ralph Miliband put it.

While Hardie, MacDonald and Wilson faced down war pressure from their own Establishment, today’s leadership appears to have forgotten that opposing imperial adventures has historically defined Labour’s moral authority, writes KEITH FLETT

Research shows Farage mainly gets rebel voters from the Tory base and Labour loses voters to the Greens and Lib Dems — but this doesn’t mean the danger from the right isn’t real, explains historian KEITH FLETT