Labour prospects in May elections may be irrevocably damaged by Birmingham Council’s costly refusal to settle the year-long dispute, warns STEVE WRIGHT

Profit before people: how pandemic restrictions ended in the 19th century

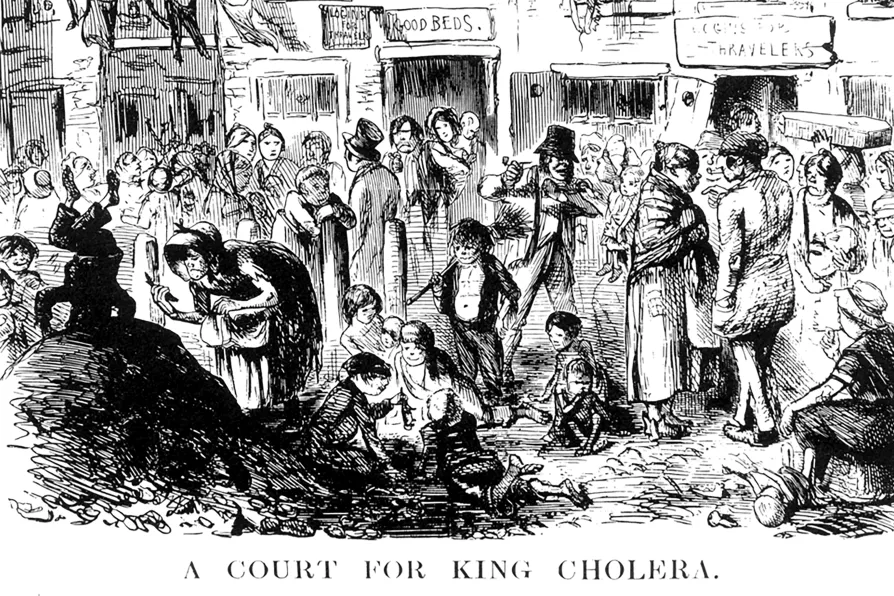

Unsurprisingly, the Tories’ reluctance to effectively fight Covid follows the same logic as the Victorian government during the cholera epidemics of the 1830s, writes KEITH FLETT

A 19th-century illustration from Punch magazine

A 19th-century illustration from Punch magazine

BORIS JOHNSON announced the end of most compulsory Covid restrictions in England on January 19.

On the same day it was announced there were 96,545 Covid infections in England and 301 reported deaths. The figures were a reduction but remain high.

In 2021 it was suggested in the other three UK nations that to lift restrictions entirely would mean infections had dropped below 50 people in 100,000.

Similar stories

The summer saw the co-founders of modern communism travelling from Ramsgate to Neuenahr to Scotland in search of good weather, good health and good newspapers in the reading rooms, writes KEITH FLETT

Starmer’s slash-and-burn approach to disability benefits represents a fundamental break with Labour’s founding mission to challenge the idle rich rather than punish the vulnerable poor, argues KEITH FLETT

The legacy of an 1820 conspiracy in revenge for Peterloo resonates down the ages, argues KEITH FLETT