ALAN McGUIRE welcomes the complete poems of Seamus Heaney for the unmistakeable memory of colonialism that they carry

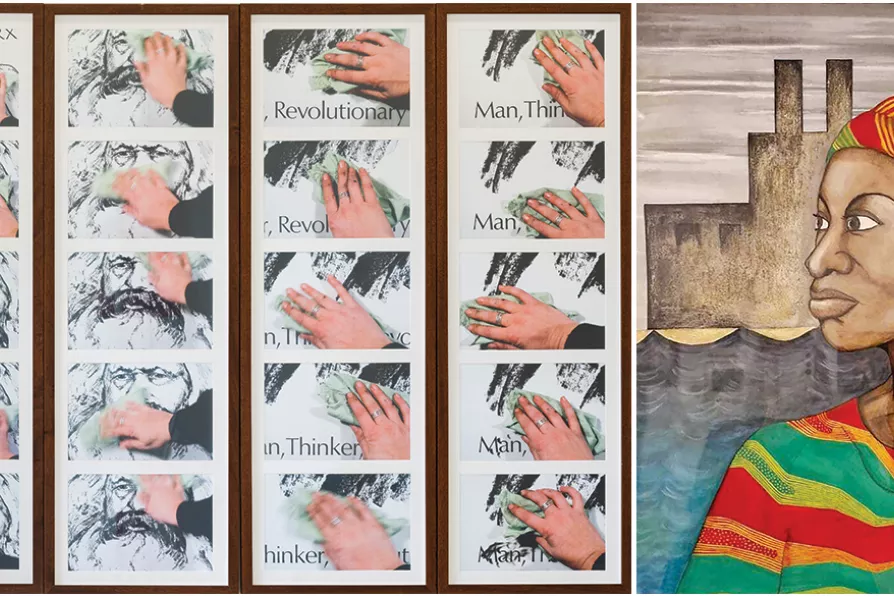

WHAT'S CHANGED? (L to R) Alexis Hunter, The Marxist Wife Still Does The Housework, 1978/2005; Stella Dadzie’s Motherland, 1984

[(L to R) Tate Britain / Author supplied]

WHAT'S CHANGED? (L to R) Alexis Hunter, The Marxist Wife Still Does The Housework, 1978/2005; Stella Dadzie’s Motherland, 1984

[(L to R) Tate Britain / Author supplied]

Women in Revolt! Art and Activism 1970-1990

Tate Britain, London

THIS is a significant, high profile and very political exhibition presenting “two decades of art as provocation, protest and progress.”

Chronologically, starting with the first women’s liberation conference in Britain in 1970, it spans second and third wave feminism (the first wave being the suffrage movement of the early 20th century). It ends somewhat arbitrarily in 1990 with a note on the commercialisation of art and the marginalisation of “artists engaged in socially motivated practices.”

For many of us caught up in the debates of the women’s movement in the 1970s the questions the exhibition raises retain much of their fascination and the diversity, awareness, experimentation and rawness of the output is nostalgic and heady. The exhibition is large, detailed and richly repays a visit.