John Wojcik pays tribute to a black US activist who spent six decades at the forefront of struggles for voting rights, economic justice and peace – reshaping US politics and inspiring movements worldwide

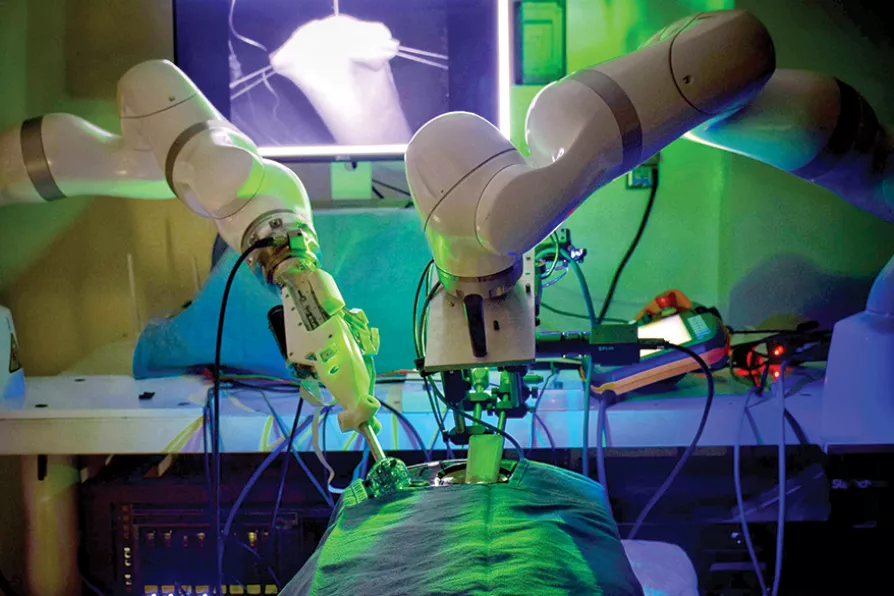

CUTTING EDGE: Smart Tissue Autonomous Robot (STAR) which can perform laparoscopic surgery on the soft tissue of a pig without human help

CUTTING EDGE: Smart Tissue Autonomous Robot (STAR) which can perform laparoscopic surgery on the soft tissue of a pig without human help

LAST month the Advanced Research and Invention Agency (Aria) announced the appointment of a new CEO, in line with its intention to launch around the end of this year.

Aria is a new funding agency modelled on venture capital funding for high-risk “moonshot” research that will sit alongside, although independent of the umbrella British research funding agency UK Research and Innovation.

The new CEO, Ilan Gur, has a background in venture capital.

Neutrinos are so abundant that 400 trillion pass through your body every second. ROX MIDDLETON, LIAM SHAW and MIRIAM GAUNTLETT explain how scientists are seeking to know more about them

A maverick’s self-inflicted snake bites could unlock breakthrough treatments – but they also reveal deeper tensions between noble scientific curiosity and cold corporate callousness, write ROX MIDDLETON, LIAM SHAW and MIRIAM GAUNTLETT

Science has always been mixed up with money and power, but as a decorative facade for megayachts, it risks leaving reality behind altogether, write ROX MIDDLETON, LIAM SHAW and MIRIAM GAUNTLETT