ALAN McGUIRE welcomes the complete poems of Seamus Heaney for the unmistakeable memory of colonialism that they carry

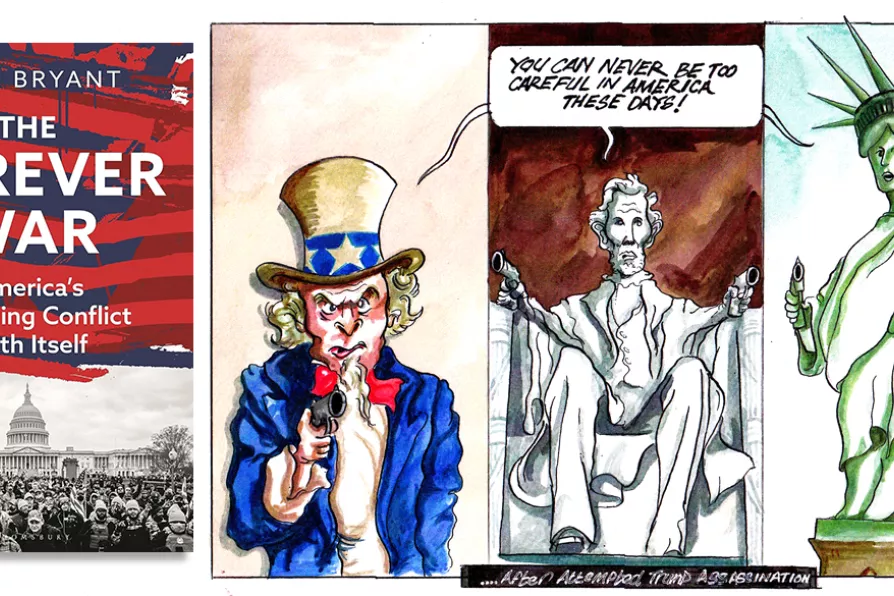

Cartoon by Steven Ashman

Cartoon by Steven Ashman

The Forever War: America’s Unending Conflict with Itself

Nick Bryant, Bloomsbury, £25

IF you select “virtually any date in US history, it would be possible to find the same poisonous ingredients [that] percolated violently to the surface on January 6, 2021,” writes journalist and historian Nick Bryant in his new book, The Forever War: America’s Unending Conflict with Itself.

Donald Trump, and the movement behind him, is both new and old; times are unprecedented but also, to historians of the US, frighteningly familiar. Bryant, a historian by training, meticulously makes sense of these contradictions, methodically unpicking the mythology of US history to clearly argue that Trump — and his support — is the product of that history.

If true, the photo’s history is a damning indictment of the systematic exploitation of non-Western journalists by Western media organisations – a pattern that persists today, posit KATE CANTRELL and ALISON BEDFORD

The global left must be unwavering in it is support for Venezuela as Washington increases its aggression, and clear-eyed about the West’s cynical motives for targeting it, says CLAUDIA WEBBE