MARIA DUARTE and ANGUS REID review Materialists, Unmoored, Together, and Bambi: A Tale of Life in The Woods

The language of the working class soldier

MARTIN HALL steps gingerly through a fragmentary novel about WWI by one of France’s greatest prose stylists, and most notorious fascist sympathisers

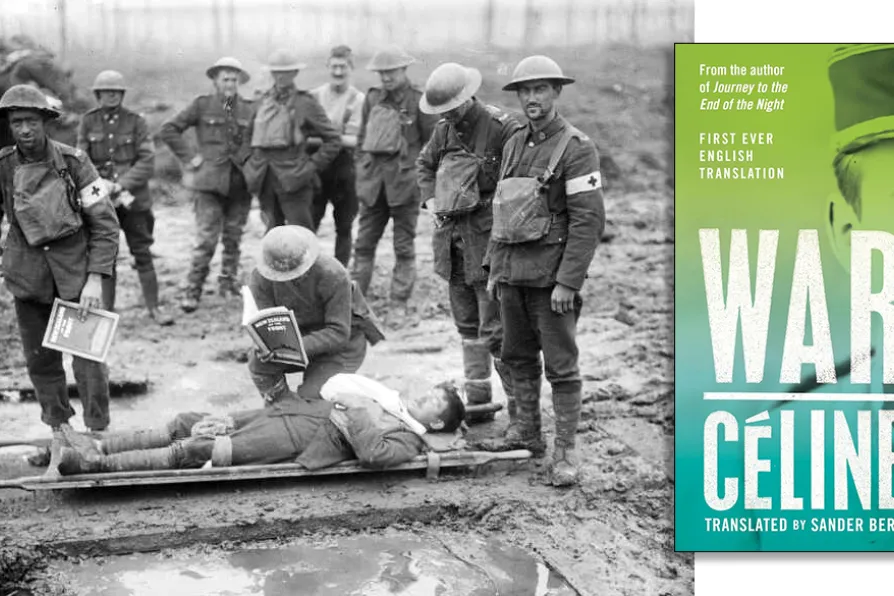

TRENCH HUMOUR: World War I soldiers of 3rd Battalion, New Zealand Rifle Brigade, reading jokes from the publication "NZ at the Front" in muddy conditions at "Clapham Junction" in the Ypres Salient, Belgium. 20 November 1917

[Henry Armytage Sanders/CC]

TRENCH HUMOUR: World War I soldiers of 3rd Battalion, New Zealand Rifle Brigade, reading jokes from the publication "NZ at the Front" in muddy conditions at "Clapham Junction" in the Ypres Salient, Belgium. 20 November 1917

[Henry Armytage Sanders/CC] War

Louis-Ferdinand Céline, translated by Sander Berg, Alma Classics, £14.99

A NEWLY discovered novel by one of France’s most celebrated writers is not a common occurrence. When that writer is Louis-Ferdinand Celine, anti-semite, collaborator and friend of fascists, there may be some readers who would prefer that it had been left lost.

However, War, written in 1934 but only discovered in 2021, is very much worth your time.

Similar stories

Travelogue/reportage by Argentinean Maria Sonia Cristoff, and poetry by Peruvian Gaston Fernandez and Puerto Rican Cristina Perez Diaz

An outstanding novel by Chilean writer and activist Pedro Lemebel, a poetry pamphlet by Venezuelan Natasha Tiniacos, and a children’s book of haikus singing the beauty of Cuba

LEIGH WILSON applauds the new translation of a novel from 1932 that is a hymn to values inimical to the forces that were growing in Germany in the early 1930s

ANDY HEDGECOCK relishes a novel by a dazzling prose stylist and a subtle player of literary games