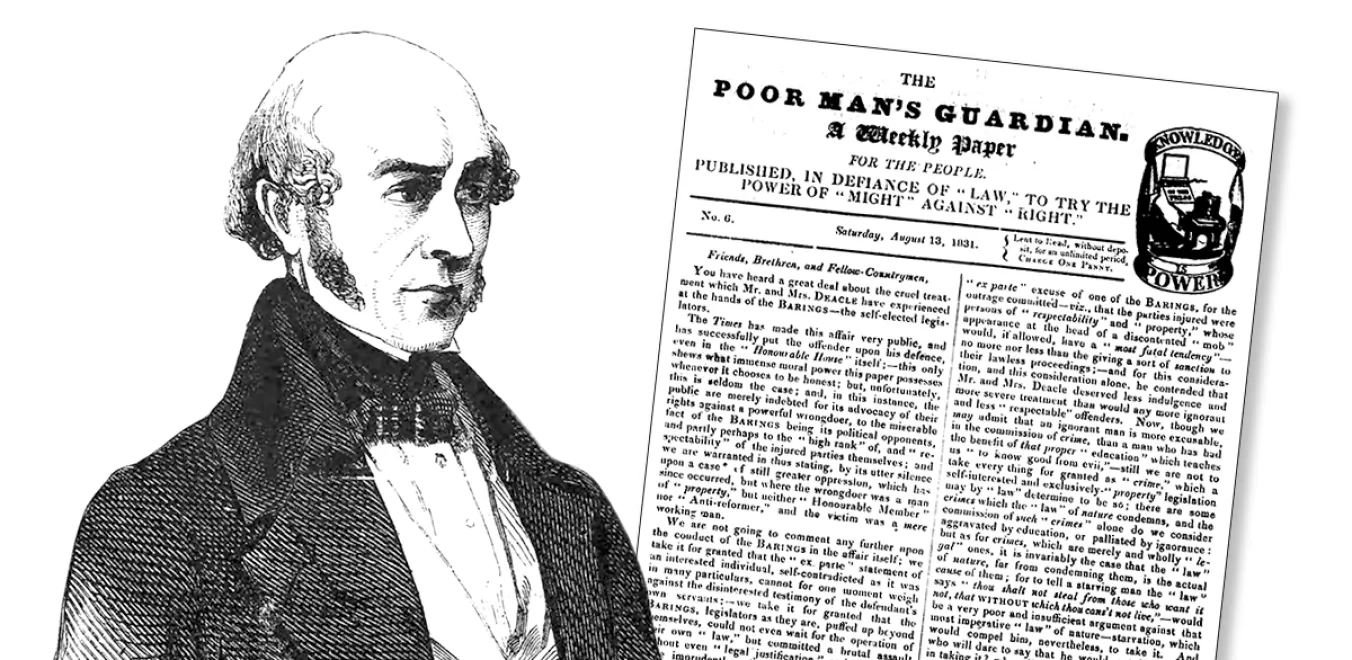

WHEN it came to opposing the Poor Law, said the reverend, it was every man’s Christian duty “to have his firelock, his cutlass, his sword, his pair of pistols or his pike, and for every woman to have her pair of scissors, and for every child to have its paper of pins and its box of needles, and let the men with torch in one hand and a dagger in the other put to death any and all who attempt to sever man and wife.”

Amen.

Clearly, he agreed with his contemporary, the Newcastle trade unionist Robert Lowery, that “All should have guns, for the man that could shoot a Pheasant would shoot a Tyrant.” (It’s often forgotten that the right to bear arms was a left-wing cause for centuries before it became identified with the US right).

Of course, we’re used to meeting “red vicars” in Rebel Britannia, but the odd thing about the Reverend Joseph Rayner Stephens is that he was no revolutionary.

For a short while, the Reverend Stephens was one of the best-known Chartist agitators in the country — but he always insisted that he was not a Chartist. He might sound red to our modern ears, but historians generally class him as a Tory-Radical, that curious 19th-century phenomenon that’s easier to recognise than to define.

Richard Oastler, who Stephens worked closely with, is the best remembered of the Tory-Radical faction, a man who believed that the old, tradition-based Toryism was being replaced by modern, ultra-capitalist Conservatism, under which the ruthless pursuit of profit and nothing else would create a spiritually dead country, disfigured by awful poverty and constant bloodshed between the classes.

Stephens, future firebrand and political prisoner, was born in Edinburgh in 1805, the son of a Methodist minister. He himself was ordained in the 1820s, starting his ministry in Stockholm and ending up in Ashton under Lyne.

But he was effectively expelled from the Wesleyan movement in the 1830s because he refused to stop campaigning for disestablishmentarianism — the idea that England should not have an official church (as it did then and does now, in the embarrassingly comical form of the Church of England).

He was also in trouble over less obscure matters. This was the time of the new Poor Law, an anti-welfare measure brought in by a free-market-obsessed government, which often resulted in families being confined in workhouses, split up into separate sexes and generations.