The Star's critic MARIA DUARTE recommends an impressive impersonation of Bob Dylan

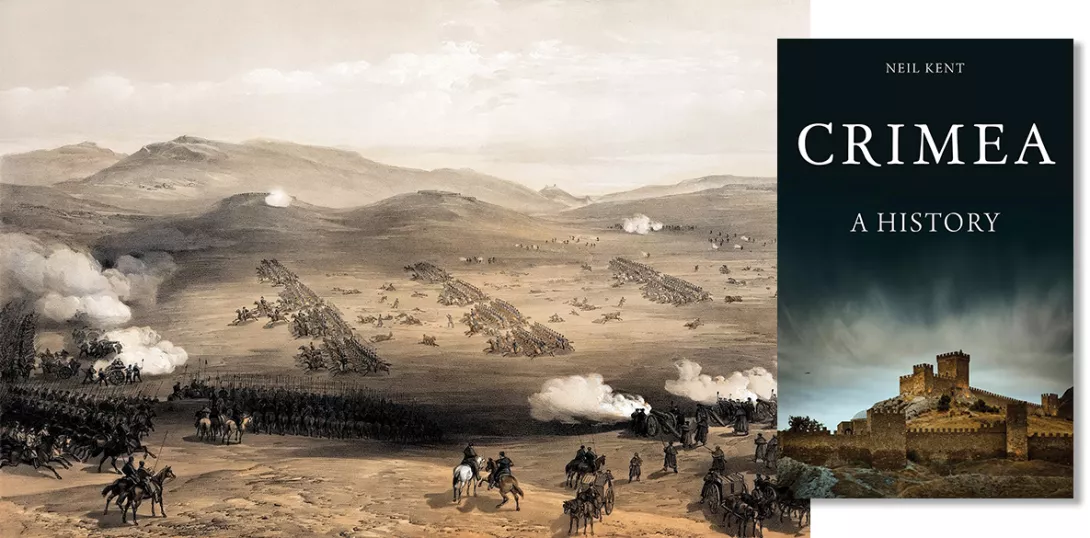

Crimea scene investigation

JOHN GREEN recommends a history of the Black Sea peninsula, situated at a crossroads between Europe and Asia

The Crimea - a History

Neil Kent, Hurst, £16.99

THIS fascinating history through the ages is essential reading for all those wishing to understand the background to the present conflict in Ukraine. In this ongoing war between Ukraine as a Nato proxy and Russia, the Crimea has played a key role.

It shapes the headlines much as it did some 160 years ago, when the Crimean War pitted Britain, France and Turkey against tsarist Russia. Yet few books have been published on the history of this peninsula. For many readers, Crimea seems as remote today as it was when colonised by the ancient Greeks.

More from this author

Driven on by novel forms of hard-right populism like Modi and Trump, European neofascists are skillfully rebranding themselves and taking power by copying the left's language — just as they did in the last century, writes JOHN GREEN

JOHN GREEN debates the potential of a book that explores fascism in US history and its contemporary impact to reach the audience it deserves

JOHN GREEN wades through the autobiography of Angela Merkel in search any trace of political vision or historical awareness

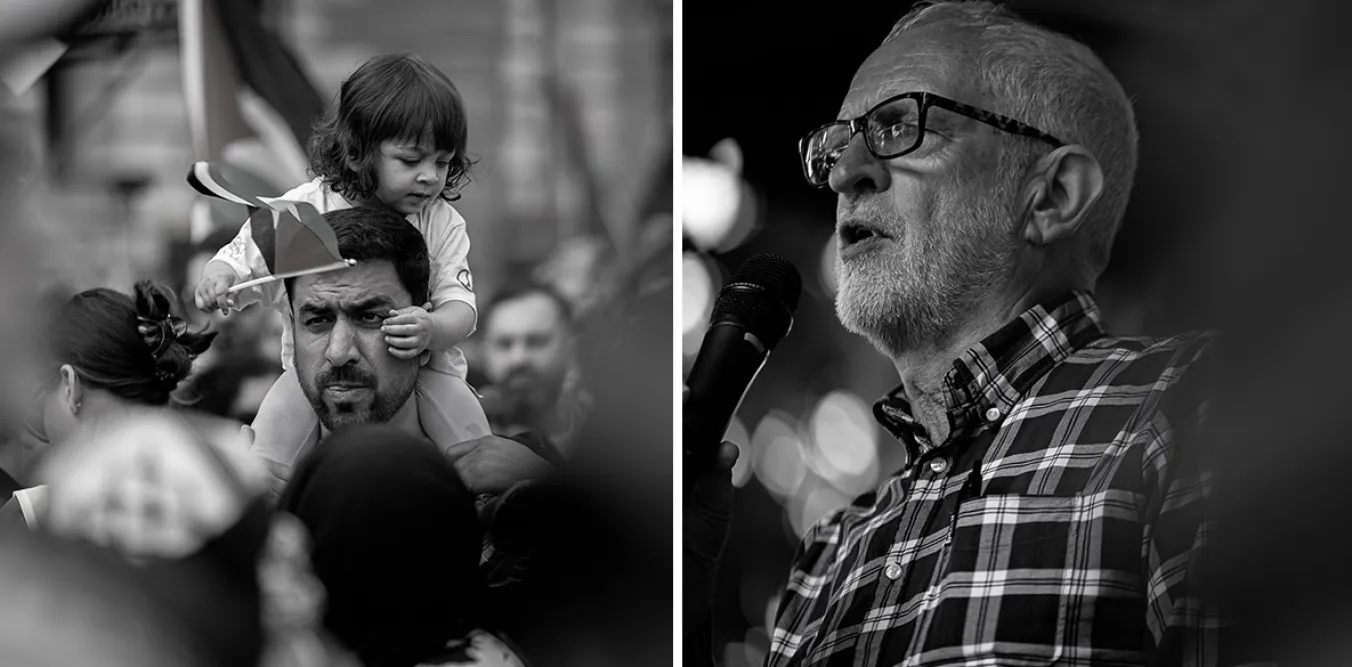

JOHN GREEN appreciates a stunning record of the pro-Palestinian demonstrations in London

Similar stories

EU's top diplomat calls on Ukraine's Western allies to allow their weapons to be used inside Russia