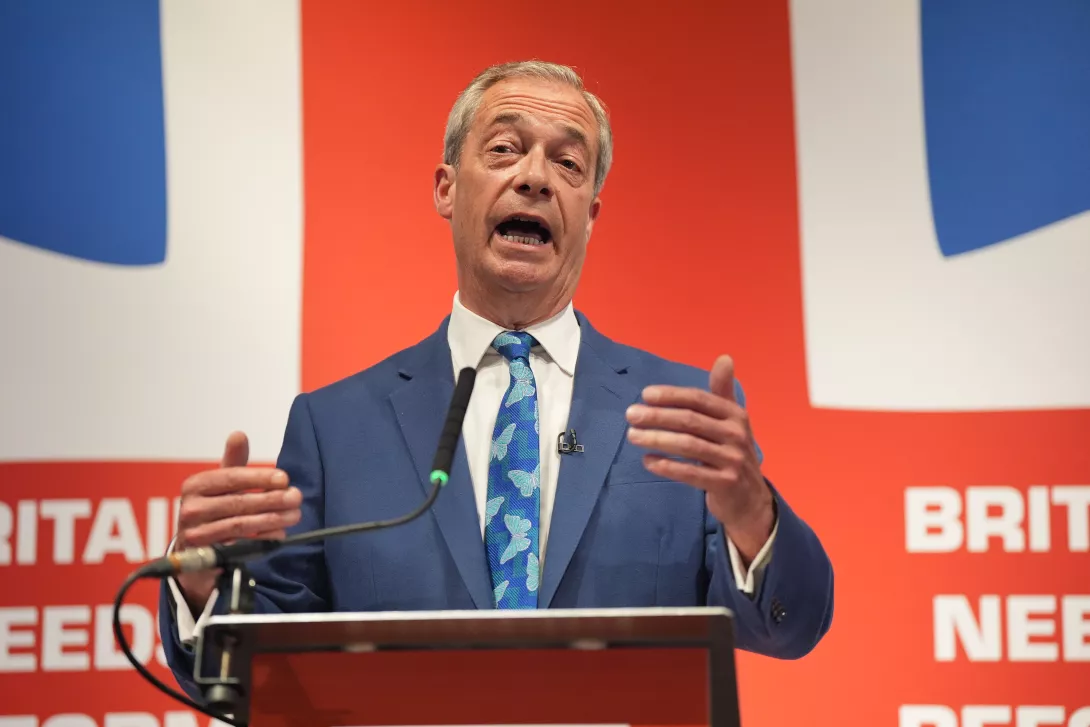

THE shadow of Nigel Farage hangs heavy over the Tory conference in Birmingham. Uniting the right is the theme of endless formal and informal debates.

That is scarcely surprising. The Tories’ huge defeat in July owed little to Conservative voters shifting to Labour, and far more to ex-Tory voters turning to Farage’s Reform UK party, or simply sitting the election out in disgust at their failures in office.

This a phenomenon reproduced elsewhere as mass centre-right parties find themselves hamstrung between their commitment to capitalist globalisation and a surging national populism.

Conservative activists claim that their party could have 100 more seats in the Commons — for a still unimpressive 221 — had just two-thirds of Reform voters plumped for the Tories instead.

This seems to considerably underestimate the problems in rebuilding an election coalition on such a basis.

Firstly, many Reform voters in working-class communities are unprepared to ever countenance voting for the Tories for class and cultural reasons. That would seem like a betrayal of traditions in a way that support for Farageist populism does not.

Secondly, moving towards a Reform agenda, majoring heavily on anti-migrant sentiment, will risk haemorrhaging votes to the Liberal Democrats or Labour, negating any gains made in one direction through losses in another.

And votes won from Reform may pile up in seats which the Tories have no realistic chance of winning, while the losses would be in marginals where the Liberal Democrats threaten.

Thirdly, while many Reform voters could be attracted to the Tories through a more strident culture war and neo-racist approach, they will be far more reluctant to sign up to the neoliberal economics that remain a central part of the Tory right’s package.

Boris Johnson, recall, married populist nationalism with the promise of state intervention to address social inequalities, even if such a pledge remained entirely unredeemed when in office.

The attraction of Reform to the Tory right persists, however, for reasons unconnected to electoral considerations. It is a lever to pull the Tory Party to the right, and to set its course in the direction they have always desired.

That is the pantomime horse of an aggressive nationalism and cultural conservatism joined to Hayekian free-market economics, making of Britain a hybrid of Singapore and Mississippi.

It is a project the left needs to take seriously. The Labour government started from a weak position in public esteem, and its own blundering combination of austerity for the poor with self-entitlement for ministers has only made matters worse since.

The idea that Starmer could be only a one-term prime minister is gaining traction among Tories. While Jacob Rees-Mogg’s call for an electoral pact with Reform is unlikely to be implemented by the next Tory leader, the project of an ideological fusion is advancing.

To prevent the danger of a hard-right takeover in 2029 or even earlier, the labour movement must act to impose a change of course on the government.

It needs to reverse austerity measures aimed at pensioners and impoverished children, introduce a wealth tax, scrap the Treasury’s fiscal rules, invest in disadvantaged communities — and explicitly challenge cultural nationalism and anti-migrant racism.

Such a programme could start to suck the air out of the putative Tory-Reform love match by addressing the problems on which it bases its appeal.

Farage and the Tories who seek to ape him are class enemies whose populist rhetoric conceals their commitment to absolutely subordinating working people to the bourgeoisie.

Asserting that fact will only defeat the hard right if backed by a serious programme to tackle the problems it feeds off. That work should start without delay.