IT WAS people taking to the streets that ended Suella Braverman’s second, if mercifully brief, period as home secretary.

Her main claim to infamy was her suggestion that “rough sleeping” is a lifestyle choice, while it was whispered on the grapevine that she wanted a law that would prevent the homeless from pitching their tents on our high streets.

Indeed among her more perverse ideas was a scheme to fine charities that provide the homeless with the very tents she aimed to ban.

As if she could not bear to abandon her heartless search for even more unfortunates to persecute, she said she made an extra point of scapegoating refugees and migrants: “… we cannot allow our streets to be taken over by rows of tents occupied by people, many of them from abroad.”

The mistress of joined-up prejudice she may be, but joined-up logical thinking is not her strong suit.

Among the factors which drive a small fraction of the global tide of refugees and migrants that find their way to our shores are the very policies of her government and its Tory, Lib Dem and New Labour predecessors.

When Afghans, Iraqis, Libyans and Syrians, for example, arrive here, their journey will often be traced back to a cataclysmic life event, family disaster or economic difficulty arising from the long history of colonial domination and the more recent experience of Nato, US and British bombing, military intervention and illegal occupation.

They are on our streets because we were on theirs.

And when Africans from the Sahara and the parched lands further south arrive here, it is because they know English as the endowment colonialism bestowed them. Africans from French colonies rarely make it to Calais’s beaches.

The main factor driving these migrant flows is the global warming and climate change crisis for which they have little responsibility.

And where they join the homeless on our streets, including not inconsiderable numbers of military veterans whose personal histories often entail the same conflicts which drove migrants and refugees here, it is our government’s responsibility to solve this crisis.

Sunak and the Marbles

IN REFUSING to meet the Greek Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis, Rishi Sunak demonstrates that extreme wealth is no guarantee of good manners, astute political judgement or deep culture.

Greece is a country with which Britain enjoys a fund of goodwill. We can still benefit from Lord Byron’s role in fighting for Greek freedom, and if our good standing is undermined to an extent by Winston Churchill’s barbaric post-war suppression of the Greek anti-fascist partisan movement, the firm support our labour movement gave to the overthrow of the cold war military dictatorship that ruled Greece in the service of Nato counts in our favour with the Greek people.

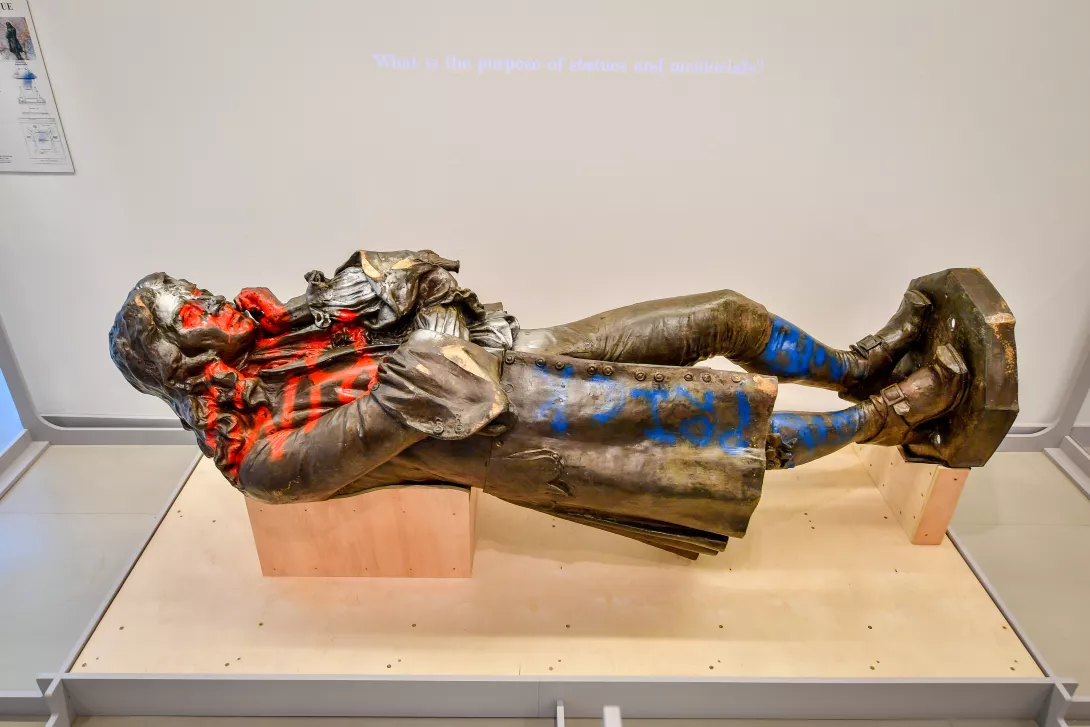

The Elgin Marbles, torn from the still-standing edifices of classical Greece, belong to the Greek people and they are displayed in the British Museum as a trophy of Britain’s 19th-century imperial might. Better we should view them in their original setting.