JOHN GREEN is fascinated by a very readable account of Britain’s involvement in South America

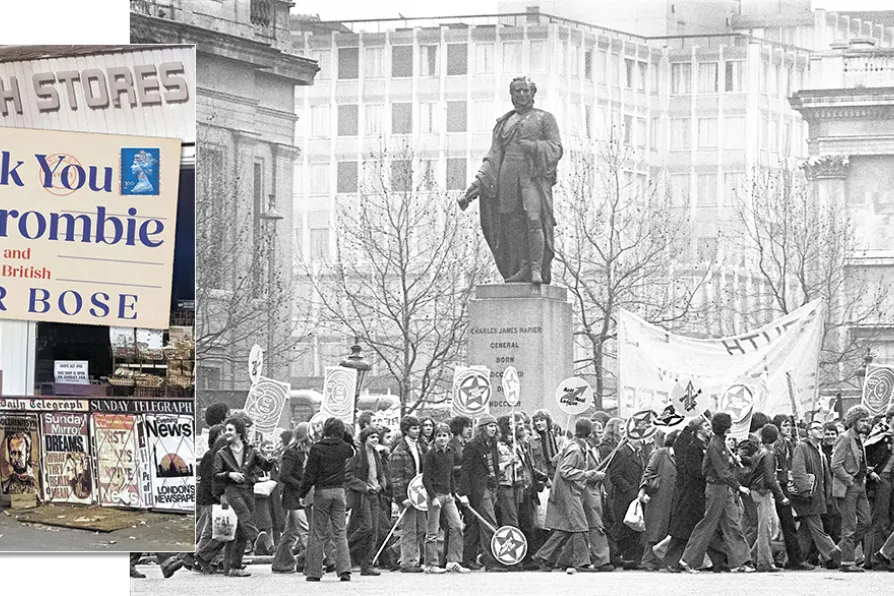

FIGHTING RACISM: Trafalgar Square, London, April 1978

[Sarah Wyld/CC]

FIGHTING RACISM: Trafalgar Square, London, April 1978

[Sarah Wyld/CC] Thank You Mr Crombie – Lessons in Guilt and Gratitude to the British

Mihir Bose

Hurst, £25

JOURNALIST Mihir Bose has produced a fascinating book chronicling his life: growing up in India, then moving to Britain, where he eventually works his way into journalism.

The title, Thank You Mr Crombie, refers to a letter Bose wrote some years later thanking the civil servant, John Crombie, who confirmed his permanent right to remain in Britain in 1975.

The great attraction of the book is the many avenues it travels down. These include the world of being brought up in a traditional Hindu family, in post-independence India. Then, the changing face of Britain that the young Bose encounters in the 1960s and early ’70s, a world that changes in the second half of the 1970s, as racist attitudes harden, with the National Front on the streets. Bose encounters racism from football supporters, as well as landlords — turning him away from renting rooms due to the colour of his skin.

Bose makes his name as a writer on sport, getting the stories behind what goes on in the sporting arena. He becomes the BBC’s first sports editor in 2006, before leaving in 2009. But he has many strings to his bow.

In the early days, he works in an engineering firm, then on to accountancy, with writing his passion, yet only a sideline at that stage. He gets his break, writing for the Sunday Times, then the Daily Telegraph.

Readers of this paper will be interested to learn how in the early 1980s, Stan Levenson, sports editor at the Morning Star, was football editor on the Sunday Times at the weekend. He was joined by Alan Bromley, who subbed for the Daily Mail during the week.

Bose declares: “Under Stan the Star had developed a superb sports desk which was a nursery for many journalists who then went on to work for the Sunday Times and other papers.”

Bose sporting scoops, like the football bungs story and the inside story of the 2012 successful London Olympic bid, will fascinate sport enthusiasts. Also, how football manager and businessman Terry Venables sought to sue him personally, rather than the title he wrote for.

But this book goes much wider than just sport and journalism.

There is much on the British empire and the relationship between Britain and India, particularly in the post-independence period, all viewed through the lens of Bose’s own personal story.

He looks at the role of Indians in collaborating in furtherance of the British empire and how the British managed to control such a large part of the world with a relatively small military force. The co-opting of native peoples ensured this was done for them. He also highlights the somewhat reductionist take on history adopted by Europeans, with a view to their own imperialist pasts.

Bose is a great observer, highlighting how football changed, with traditional white working-class people moving out from areas around city centre-based football grounds. They were then replaced by migrant communities, who in the early days had little interest in the sport.

Another observation is the evolution of Indian food to suit the British palate and how this went from an alien import to become the most popular food in Britain.

Bose also admires the abilities of Indians and English to adjust to each other. The flexibility of society to react and change.

If I have a criticism, it is when Bose chronicles the early years of growing up in a traditional Hindu family in Mumbai. He provides fascinating insights but at times the detail is too dense and his coverage of all the religious customs drags a bit.

The lack of any photos accompanying a life in the media is also odd.

However, overall this is a fascinating read. Accessible, entertaining and covering a vast canvas through the story of one man.

Highly recommended.

JOHN GREEN is fascinated by a very readable account of Britain’s involvement in South America