Gloucestershire’s phlebotomists have brought their historic strike to a close after almost a year of action, leaving a legacy of determination – and a clear lesson about the power of solidarity in the face of anti-union laws and austerity, says FBU general secretary STEVE WRIGHT

THE Good Food Guide has its roots in a unique account of the 1926 General Strike. Although edited by a prominent journalist, A Worker’s History of the Great Strike wasn’t a top-down record of events as seen from the centre but was based on direct reports from activists nationwide.

As explained in the introduction, “In effect the writing of this book is a first essay in a form of co-operative inquiry which we believe will be to the greatest benefit of the workers if it can be extended.”

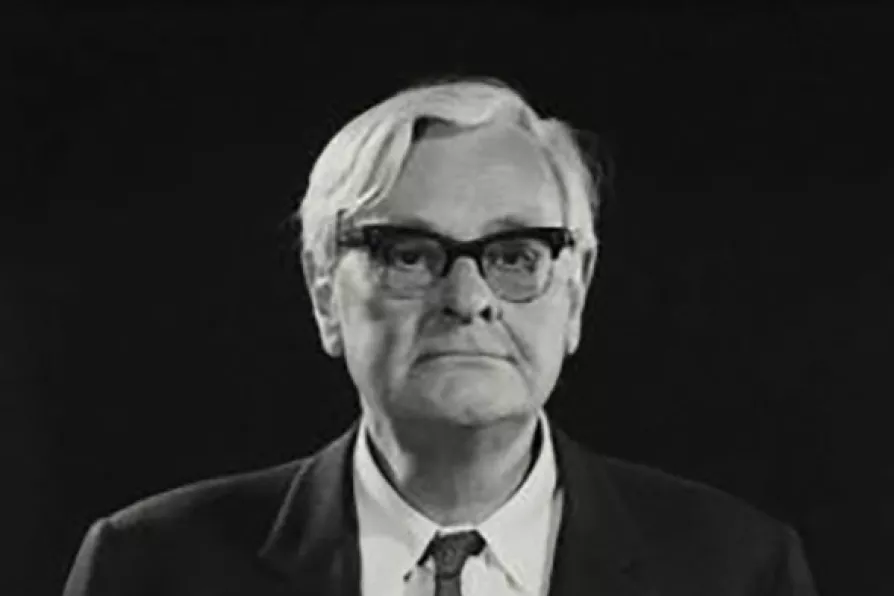

Many years later that book’s editor, Raymond Postgate, used the same proto-wiki style of knowledge pooling to create The Good Food Guide. In between and either side of those two achievements, he spent time as a political prisoner, was a founding member of the Communist Party of Great Britain, got sued by Babycham, and became one of the most lauded writers of British crime fiction — based on just one novel.

Latest editorial

Latest editorial