Climate activist and writer JANE ROGERS introduces her new collection, Fire-ready, and examines the connection between life and fiction

ALEX HALL is thrilled by a grassroots history of of Swindon’s stunning industrial and creative past

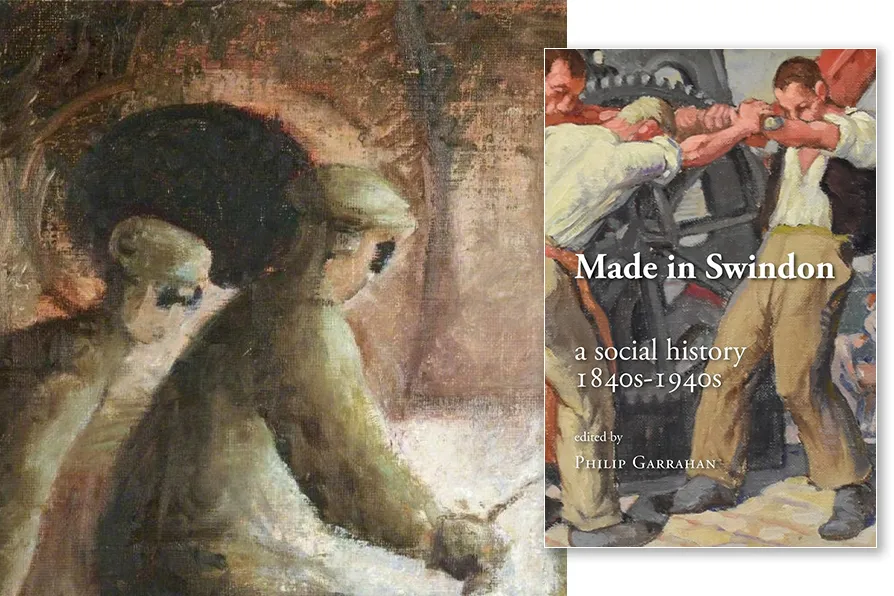

Foundry, Hubert Cook (1901 - 1966). Cook was a painter, printmaker and teacher who was educated and worked in Swindon. [Pic: Courtesy of Museum & Art Swindon]

Foundry, Hubert Cook (1901 - 1966). Cook was a painter, printmaker and teacher who was educated and worked in Swindon. [Pic: Courtesy of Museum & Art Swindon]

Made in Swindon: A Social History 1840s-1940s

Philip Garrahan, Hobnob Press, £16.95

FEW towns in the south of England have been as battered by neoliberalism as Swindon, and the town centre can be depressing as much as it can demonstrate diversity and energy. Over the last 40 years, production has been replaced by consumption. But the town that has been frayed by capital was also created by capital, and the movements that came with it.

In 1840 Swindon was a village on top of a hill in agricultural Wiltshire with a population of 2,500. The Anglo-Saxon name of the village literally means “Pig hill.” But the directors of Great Western Railway had permission to build their London-Bristol line, Swindon Junction was opened in 1841, and Swindon became the location chosen to build locomotives and carriages.

The area was utterly transformed from agricultural to industrial, and by 1939 the population was 40,000 of whom 14,000 entered GWR Works daily. Swindon was a company town through and through. But the transformation wouldn’t have been possible without providing housing and public services for the workforce.

Infectious diseases remained prevalent, the workforce needed education, healthcare, and entertainment. Some of this was provisioned by the company, but much was also provisioned by the workers.

This collection of contributions from professional and lay researchers including proud Swindonians is a welcome history of this transformative time. The lens is firmly on the workers, their innovations, institutions and interactions with the company structures. We hope, however, that the role of women in Swindon (such as Edith Stevens) is detailed in a later volume.

The Medical Fund Society was set up in 1847 and run as a mutual aid society, managed by workers democracy. Over a century before the NHS, healthcare was provided by mutual subscription to build the infrastructure and employ the doctors and nurses.

At first the GWR bosses supported this innovation financially, but also by compelling all employees to join the Society. Thus they also relieved themselves of some responsibility for the health and safety conditions that came with 19th-century industry.

The Mechanics Institute was created in 1843, and provided for the social and educational needs of the workers and their families. A prime example of Victorian industrial design it housed a library and theatre, and hosted a market. “The Mechanics,” as it came to be known, ran lectures, evening classes and promoted performances.

For 20 years from the 1930s Swindon Mechanics became a leading centre of opera, hosting numerous Rimsky-Korsakov pieces. Again, GWR supported this innovation as of course it relieved the costs of providing an education to the workforce.

Both the Medical Fund and Mechanics were run democratically, well before the working man was allowed to vote in general elections.

Further contributions tell the account of the autodidact Alfred Williams who taught himself four languages including Sanskrit, writing school textbooks, detailed accounts of rural Wiltshire, life at the factory, and poetry. This was achieved despite his day job being a labourer at the steam hammer, a job he detested.

Swindon had a notable and highly productive art output. Initially conceived to assist workers produce recognisable and beautiful industrial output for the benefit of capital, this developed into significant socially inspired art, including notable local artists Harold Dearden, Hubert Cook and Leslie Cole. The latter became a war artist and was present at the liberation of Bergen-Belsen extermination camp and a Japanese internment camp for women, both of which he painted.

Made in Swindon is an unusual book in that it details the grassroots and comes from the grassroots. It transforms one’s view of Swindon from a slightly depressing nondescript former industrial town to one with a vibrant workers’ history, and much to be proud of.