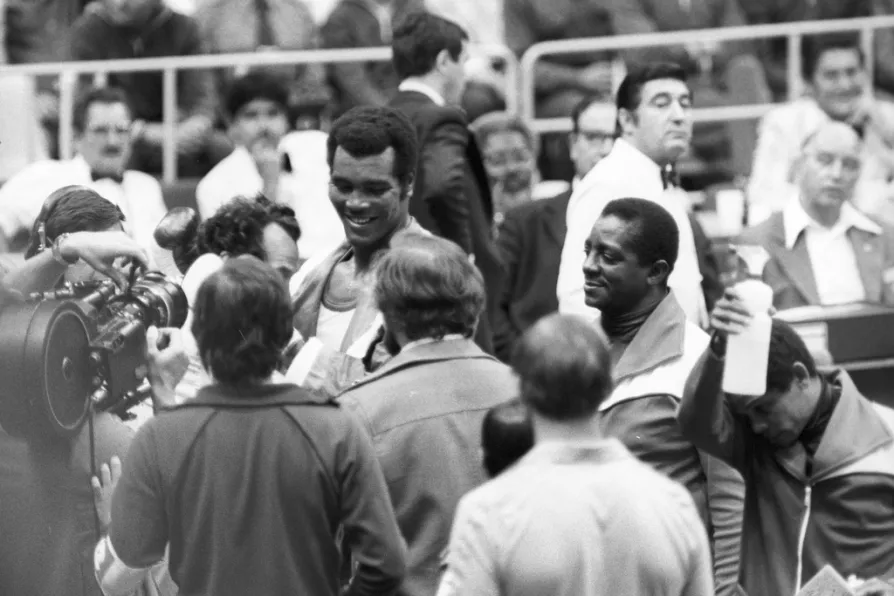

Teofilo Stevenson talking with journalists during the 22nd Summer Olympic Games held in Moscow in 1980

[RIA Novosti archive / Creative Commons]

Teofilo Stevenson talking with journalists during the 22nd Summer Olympic Games held in Moscow in 1980

[RIA Novosti archive / Creative Commons]

THESE were the words of the legendary Cuban amateur heavyweight, Teofilo Stevenson, in response to a lucrative multimillion dollar offer to turn pro and fight Muhammad Ali after the Montreal Olympics in 1976. They remain as powerful a testament to the nature and character of the Cuban Revolution today as they did when spoken over 40 years ago.

Stevenson dominated world amateur heavyweight boxing in a career that spanned 14 years and three Olympic Games. He returned to Cuba on each occasion with a gold medal to make him one of only three boxers to achieve this remarkable feat in the history of the Games, among them fellow Cuban Felix Savon.

To add to his haul of three Olympic golds, Stevenson also won three World Amateur Boxing Championship gold medals and a further two golds at the Pan American Games, before announcing his retirement in 1986 at 34.

JOHN WIGHT tells the riveting story of one of the most controversial fights in the history of boxing and how, ultimately, Ali and Liston were controlled by others