Black & White Knight

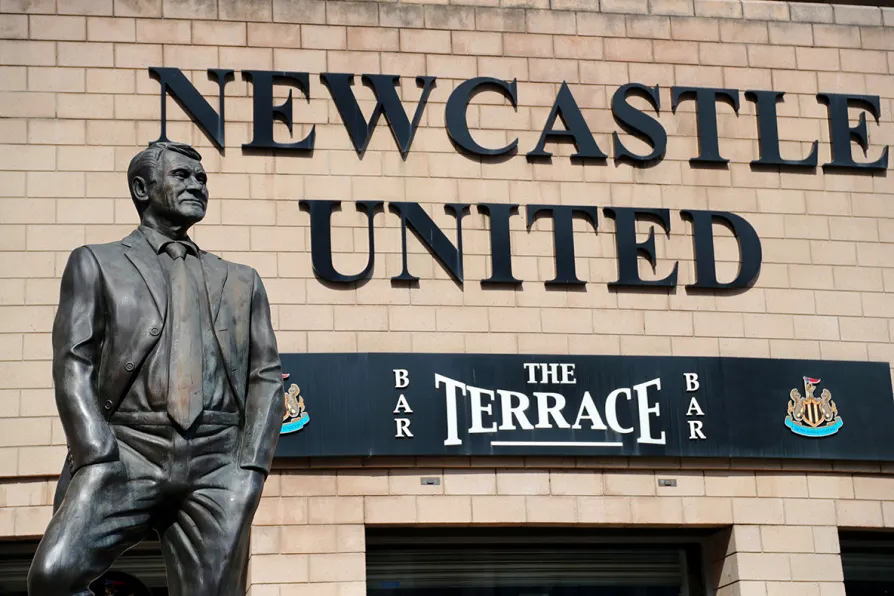

A statue of Sir Bobby Robson outside The Terrace Bar ahead of a Premier League match at St James' Park, Newcastle

A statue of Sir Bobby Robson outside The Terrace Bar ahead of a Premier League match at St James' Park, Newcastle

IT’S rare that an English football figure garners widespread acclaim and respect beyond the British Isles, but this something the late Sir Bobby Robson was able to do thanks to his time working as a manager across Europe.

Robson managed more clubs outside of England than he did in it, and even in his first successful and most prolonged stint as a manager of one club, Ipswich Town, he tasted success in Europe winning the Uefa Cup in 1981.

His success in Suffolk earned him the England manager’s job in 1982, a role he held until after the 1990 World Cup making him the third longest-serving England manager in history.

Similar stories

A celebration of Diogo Jota and his time in English football, after he and his brother Andre Silva died following a car accident in the early hours of Thursday morning in Spain. By JAMES NALTON

DAVID CONWAY writes how recognising trade unions for non-playing staff could help the club rediscover success both on and off the football pitch

Victims were forgotten until a far-right billionaire posted a series of tweets on Britain’s grooming gangs. ANN CZERNIK separates the grains of truth from the chaff of media frenzy in the story that has appalled one and all