MARJ MAYO recommends a lyrical and disturbing account of the tragic suicide in Venice of Pateh Sabally, a refugee from the Gambia

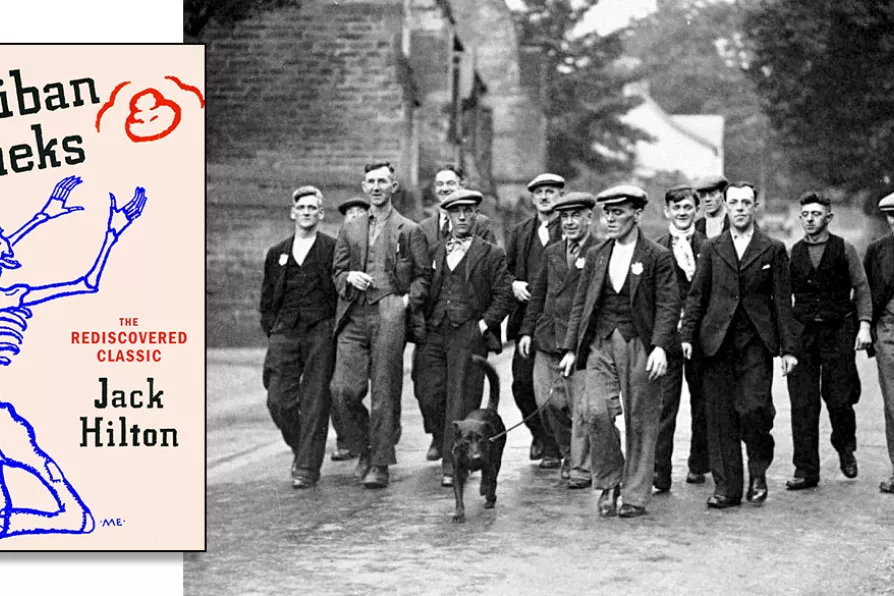

Unemployed workers from Jarrow marching to London in 1936

[National Media Museum/CC]

Unemployed workers from Jarrow marching to London in 1936

[National Media Museum/CC]

Caliban Shrieks

Jack Hilton, Vintage Classics, £16.99

BILLING a novel as “the rediscovered classic” makes it a hostage to fortune: there’s a danger readers will focus on the literary detective work implied by that strapline at the expense of the book itself. In this new edition of Caliban Shrieks, a book first published in 1935, the risk is exacerbated by two absorbing introductions.

In the first, poet Andrew McMillan situates Jack Hilton’s work in the traditions of experimental and working-class fiction, lamenting the capricious nature of literary reputation and the enduring influence of regional and class inequalities in the arts.

In the other, Jack Chadwick focuses on his serendipitous encounter with a copy of the original edition in Salford’s Working-Class Movement Library. His fascination with this yellowing volume led him to delve into the author’s life and, ultimately, to bring the book back into print. Chadwick’s quest amplifies one of Hilton’s major themes — the crushing limitations imposed on working-class culture by capitalism.

Looking for moral co-ordinates after a tough year for rational political thinking and shared human morality

Looking for moral co-ordinates after a tough year for rational political thinking and shared human morality

New releases from The Dreaming Spires, Bruce Springsteen, and Chet Baker