STEPHANIE DENNISON and ALFREDO LUIZ DE OLIVEIRA SUPPIA explain the political context of The Secret Agent, a gripping thriller that reminds us why academic freedom needs protecting

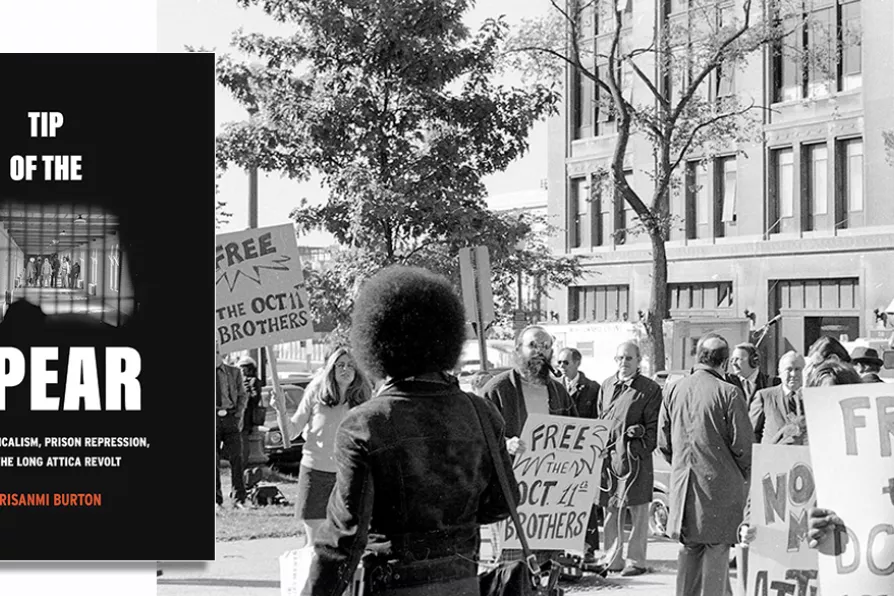

REVOLUTIONARY ACTS: Demonstrators demand the release of the “October 11 Brothers” in February 1974 on trial after the October 11 1972 uprising The Central Detention Facility DC

[Washington Area Spark/Reading/Simpson/flickr/CC]

REVOLUTIONARY ACTS: Demonstrators demand the release of the “October 11 Brothers” in February 1974 on trial after the October 11 1972 uprising The Central Detention Facility DC

[Washington Area Spark/Reading/Simpson/flickr/CC]

Tip of the Spear: Black Radicalism, Prison Repression, and the Long Attica Revolt

by Orisanmi Burton

University of California Press, £23.59

THIS new book changes the narrative around the 1971 Attica Prison Revolt in a substantial, even revolutionary way.

In the text, Burton reframes the uprising at Attica State Prison in 1971 as part of an ongoing revolt. In doing so, he shifts the emphasis from the massacre by law enforcement that is most present in other tellings. In addition, his repositioning of that incident as part of a longer, ongoing movement by black, Latino and other prisoners for the abolition of prisons and jails in general makes the history of Attica a living fact.

RON JACOBS is enthralled by an account of the surveillance and political repression on the left in the US

RON JACOBS welcomes a survey of US punk in the era of Reagan, and sees the necessity for some of the same today

RON JACOBS salutes a magnificent narrative that demonstrates how the war replaced European colonialism with US imperialism and Soviet power