As Colombia approaches presidential elections next year, the US decision to decertify the country in the war on drugs plays into the hands of its allies on the political right, writes NICK MacWILLIAM

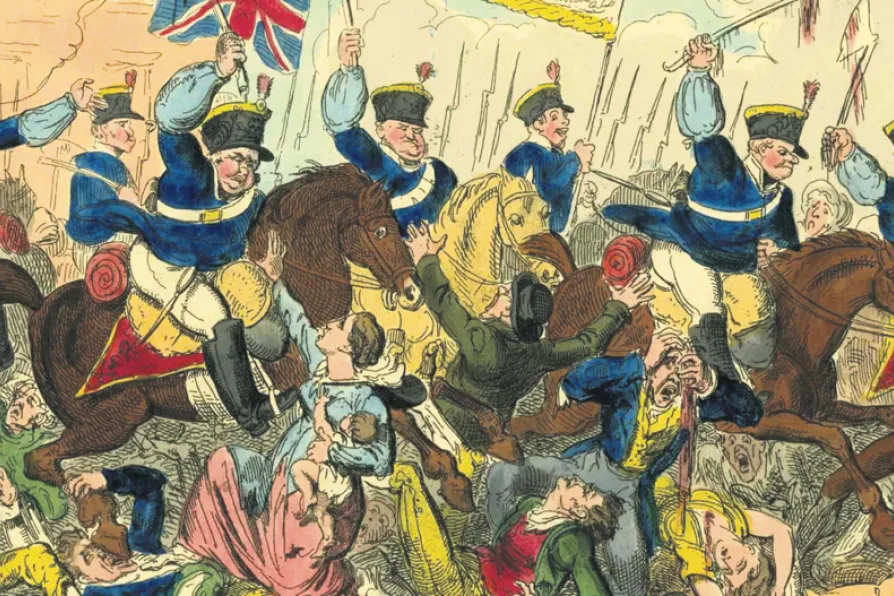

The charge of the Yeomanry left 15 marchers dead

The charge of the Yeomanry left 15 marchers dead

WILLIAM HULTON (1787-1864) is not a name that features significantly in British history, he deserves more recognition, as does what eventually happened to the vast estate he owned on the edge of what is now Greater Manchester.

It’s thought that the Hulton family may have held the land since as early as 989AD, which made it until very recently the longest period in which a piece of land had been held by a single family in British history.

Hulton came into his inheritance in 1808 aged 21 and married Maria who bore him 13 children.

In 1981, towering figure for the British left Tony Benn came a whisker away from victory, laying the way for a wave of left-wing Labour Party members, MPs and activism — all traces of which are now almost entirely purged by Starmer, writes KEITH FLETT

Who you ask and how you ask matter, as does why you are asking — the history of opinion polls shows they are as much about creating opinions as they are about recording them, writes socialist historian KEITH FLETT

KEITH FLETT revisits debates about the name and structure of proposed working-class parties in the past

The summer saw the co-founders of modern communism travelling from Ramsgate to Neuenahr to Scotland in search of good weather, good health and good newspapers in the reading rooms, writes KEITH FLETT