VIJAY PRASHAD details how US support for Syrian President Ahmad al-Sharaa allowed him to break the resistance of the autonomous Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF)

New research into mutations in sperm helps us better understand why they occur, while debunking a few myths in the process, write ROX MIDDLETON, LIAM SHAW and MIRIAM GAUNTLETT

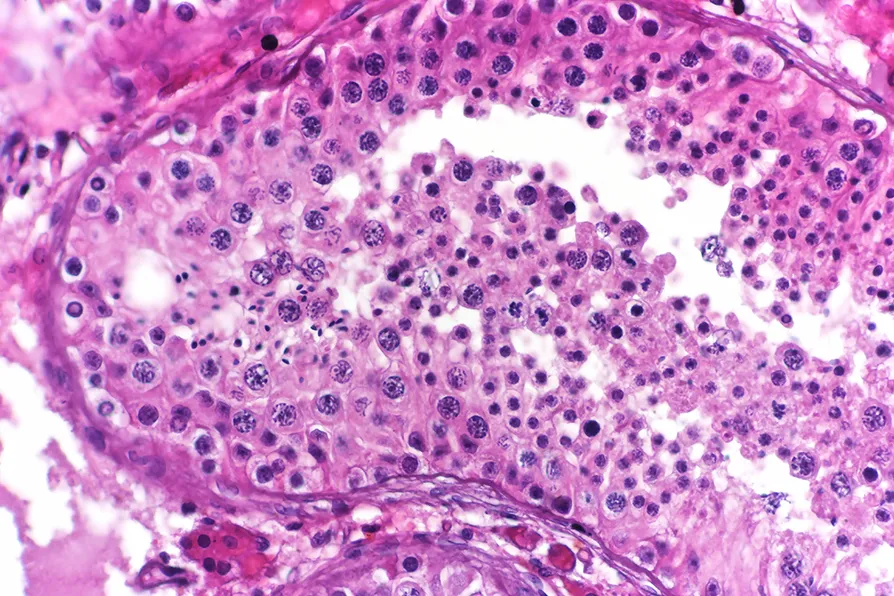

LIFELONG MUTATIONS: Spermatogenesis commences during puberty and continues throughout life and until old age because of the inexhaustible stem cell reservoir - an abundance of germ cells are developed and delivered / Pic: CoRus13/CC

LIFELONG MUTATIONS: Spermatogenesis commences during puberty and continues throughout life and until old age because of the inexhaustible stem cell reservoir - an abundance of germ cells are developed and delivered / Pic: CoRus13/CC

THE development of life on Earth means that every living organism is related to every other.

Whatever the pair of organisms, if you could rewind history and trace their evolutionary paths back in time, eventually you’d reach a common genetic ancestor.

Two siblings need go back only one generation; two cousins two generations; for a person and their dog, about 85 million years.

It’s the mutation of genetic material through history that has produced the diversity of life we see today.

In humans, the cells that combine to pass on genetic material are egg cells and sperm cells. These are known as the germline cells. All the other types of cells that make up our bodies – from red blood cells to bone cells, skin to muscle – don’t get passed on. Whatever happens to them in our lifetimes dies with us.

That doesn’t mean that they don’t evolve. Within our bodies, our cells are always accumulating mutations.

These can arise from external damage, like when photons of ultraviolet light give a DNA molecule a jolt of energy and break it apart, or from our internal cellular processes of DNA replication that intrinsically make a small number of copying mistakes.

From experiments with known causes of mutation (such as tobacco smoke or radiation) it’s been possible to work out their characteristic signatures in the genome, but recent studies have shown that not all sources of mutations that happen in our bodies are understood.

The upshot is that mutations are happening all the time. Most of these mutations are harmless, but each time a cell picks one up it will be passed onto all its descendants within the body. That means that mutations build up over our lifetimes.

One estimate from 2016 is that the rate is about 40 new mutations per cell per year. We have three billion “letters” of DNA in our genome, so even adding up these changes over a lifetime is only a tiny fraction of difference.

But this tiny fraction does create a patchwork of genetic relatedness in our bodies: we are all mosaics of very closely related cells, sharing almost (but not exactly) the same genome.

Most of these mutations are harmless, but some of them can have negative effects. For example, they can make a cell start to divide more quickly than it would otherwise, creating a lump of related cells that grows where it shouldn’t. This is the problem of cancer.

However, usually these mutations aren’t in the germline cells. So if a person with cancer has children, the changes that developed the cancer won’t be inherited by the next generation. But each time the germline blooms to make another body, new mutations could make cancer happen again.

It’s reasonable to ask why cancer happens at all. Surely natural selection should have eliminated it? But natural selection only “cares” about the passing on of genetic information between generations, not about how long, happy or illness-free an organism’s life is.

Moreover, our best understanding of the propensity for cancer is that it’s intimately linked to things our cells need to do.

For example, during the early development of an embryo cells need to grow and divide quickly to build a body. These are “cancer-like” properties. So organisms that evolved to be less prone to cancer would experience other difficulties.

Natural selection is about trade-offs, and it seems that the possibility of developing cancer is one of them.

Most mutations that occur in our bodies aren’t passed on to the next generation. However, mutations in the germ cells can be.

All egg cells are formed in a foetus before it’s even born, meaning any copying errors are already in place before birth. Sperm cells, however, are regenerated by cell division throughout a person’s lifetime. This means that any mutations they accumulate through time are passed on.

It’s been established for some years that sperm cells gain increasing mutations over a lifetime.

Now, a recent study published in Nature has studied sperm samples from individuals between the ages of 24 and 75, with new techniques allowing researchers to accurately calculate the rate of mutation accumulation.

They find that on average sperm cells gain between 1 and 2 mutations a year, more than previously thought.

These mutations are retained because of ongoing evolution inside the population of sperm cells. Natural selection within this population will favour sperm cells that are better at dividing more quickly, and over time these mutated sperm cells will have more descendants.

Unfortunately, these mutations are often associated with a higher rate of cancers and developmental disorders, which makes sense given the “cancer-like” property of faster division.

This means older sperm cells carry more risk of developmental disorders. The study’s estimate is that 3-5 per cent of sperm from men older than 50 carry a potentially dangerous mutation.

It’s difficult to estimate what the actual impact of these mutations could be in pregnancy, but many fertilisations from sperm with these mutations would probably not progress into long-lasting pregnancies.

An improved understanding of risk has potential to enhance healthcare, but the dark and ongoing history of eugenics looms large when carrying out and interpreting this kind of research.

Some scientists have been too eager to claim omniscience about who should and shouldn’t have children. So it’s worth emphasising that when viewed in context, the pre-conception genetic risk outlined by this study is just one risk among many. The dramatic and often heartstopping uncertainty of pregnancy, and of a whole human life, is impossible to fully quantify.

Historically, the increasing risks associated with age and pregnancy have been blamed almost entirely on women. There is still a misogynistic strain of discourse in the medical profession that views older women becoming mothers as somehow an irresponsible act.

What this recent research into sperm cells makes clear is that the reproductive risks of ageing apply to everyone, contributing to correcting a historic imbalance and improving our understanding of basic biology.

Changing patterns of parenthood are linked to changes in society; the pattern of people choosing to have children when they’re older is because of a complex mixture of economic and social forces, not because of a rational assessment of scientific risk.

Everyone deserves reproductive freedom. Medical research should never be used to judge or attack people if they decide they want biological children – at any age – or, for that matter, if they don’t.

Neutrinos are so abundant that 400 trillion pass through your body every second. ROX MIDDLETON, LIAM SHAW and MIRIAM GAUNTLETT explain how scientists are seeking to know more about them

Olive oil remains a vital foundation of food, agriculture and society, storing power in the bonds of solidarity. Though Palestinians are under attack, they continue to press forward write ROX MIDDLETON, LIAM SHAW and MIRIAM GAUNTLETT

ALEX DITTRICH hitches a ride on a jaw-dropping tour of the parasite world