Labour prospects in May elections may be irrevocably damaged by Birmingham Council’s costly refusal to settle the year-long dispute, warns STEVE WRIGHT

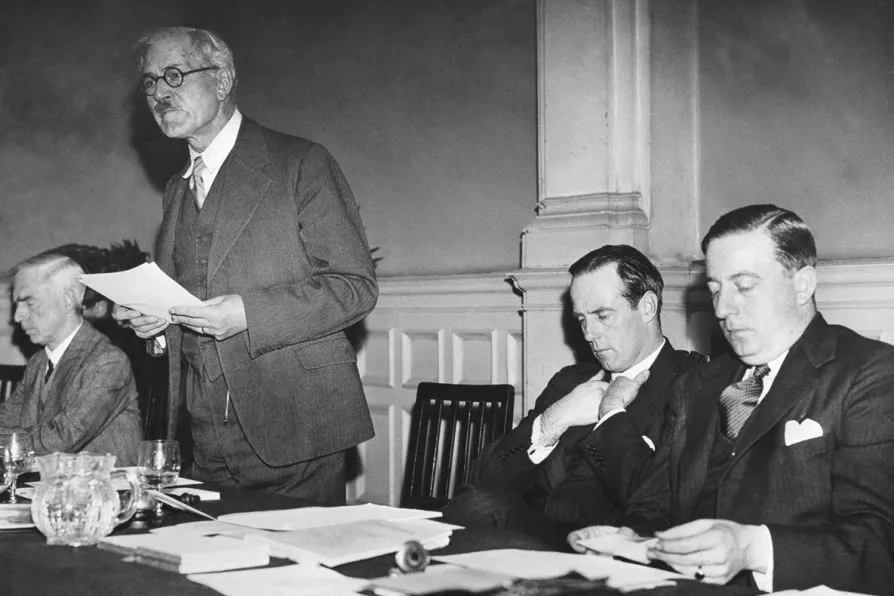

Ramsay Macdonald speaking at the national Labour Conference. (L to R Hon.R.D. Denam, Macdonald, C.E. Asquith, H.Stannard), 1936

Ramsay Macdonald speaking at the national Labour Conference. (L to R Hon.R.D. Denam, Macdonald, C.E. Asquith, H.Stannard), 1936

ON December 6 1923, Britain faced its second general election in a year. The governing Tory Party was seeking a fresh mandate for several imperialist policies they wanted to pursue after the first world war. Things didn’t work out as planned.

While the Tories won most seats they did not have a majority. Labour with 191 seats and the Liberals with 158 could outvote them.

The two ruling-class parties had fallen out, and the Liberals eventually determined to support a minority Labour government. The anniversary of that is in January 2024.

An event to mark the occasion was held at the People’s History Museum in Manchester on December 2 and was attended by deputy Labour leader Angela Rayner.

It is quite rare in recent times for Labour to acknowledge anything much about its history. Keir Starmer was unavailable due to being at Cop28. It was a convenient absence since Starmer appearing at an event which marked the appointment of Ramsay MacDonald as prime minister might have led to awkward questions.

Turning however to the election itself, what role did the left play? MacDonald had only recently been elected leader again in a contest with JR Clynes. MacDonald had not supported the first world war and lost his seat at the 1918 general election. He returned to Parliament for Aberavon at the 1922 Election.

The Tories had been dismissive of MacDonald as being too extreme to be a real threat at the polls — this seems odd to socialists who know MacDonald primarily for his disgraceful role in the 1931 national government.

However, in 1923 the Tory media saw MacDonald as a pacifist, someone who was opposed to the British empire, and indeed, someone who might even be something of a Bolshevik.

The election was dominated by media and Tory-promoted hysteria around Bolshevik plots which led the following year to the notoriously forged Zinoviev letter.

Writing in 2019 the commentator Andrew Marr noted: “The bigger picture was that MacDonald’s Labour showed it could govern. In many ways, the winter election of 1923 was an essential precursor to 1945.”

Be that as it may, that first minority Labour government was hardly a beacon of socialist practice.

Another election was called for October 1924 and on this occasion, Baldwin won a clear majority. Labour lost 40 seats but gained a million more votes.

It was not a surprise for the left however that MacDonald’s government didn’t last.

JT Murphy, writing in the December 1923 edition of the CPGB’s The Communist, argued that the election was really about promoting a new drive to imperialist war and that Labour needed to harness the power of the international working class to address this.

He argued that the utter failure to do anything in this latter direction, owing to parliamentary and bourgeois obsessions, “lands the Labour Party’s proposals into the same category as those of Baldwin, Smuts and Wilson. What is the use of Labour holding aloft the banner of socialism if its deeds are the deeds of imperialism?”

Even so, the article called for support for Labour as a class vote.

The parallels with 2023 are striking. The Tories may accuse Labour of radical policies that Starmer and Rachel Reeves have long since purged from the agenda. Even so, many will be pleased to see a hard-right Tory government ejected from office at the general election.

For the left, the problem is clear. A century ago as now in terms of socialist advance, this represents only the most limited progress.

Keith Flett is a socialist historian. Follow him on X @kmflett.

While Hardie, MacDonald and Wilson faced down war pressure from their own Establishment, today’s leadership appears to have forgotten that opposing imperial adventures has historically defined Labour’s moral authority, writes KEITH FLETT

Research shows Farage mainly gets rebel voters from the Tory base and Labour loses voters to the Greens and Lib Dems — but this doesn’t mean the danger from the right isn’t real, explains historian KEITH FLETT

KEITH FLETT traces how the ‘world’s most successful political party’ has imploded since Thatcher’s fall, from nine leaders in 30 years to losing all 16 English councils, with Reform UK symbolically capturing Peel’s birthplace, Tamworth — but the beast is not dead yet